There has been some discussion about the surplus of American proprietary hops since my previous article. The surplus that nobody wanted to claim is out there now. The problem is much larger and more serious than anybody will admit … until now.

If you’ve been reading my articles for a while, you already knew about this. I wrote an article back in October 2022 called “Massive Hop Inventory in the U.S.” that went into some detail on the problem. You can read it here if you like. Merchants are finally admitting it’s not normal for massive inventories to appear just because there are so many brewers and so many acres in production. This is a great example of hop industry propaganda used to maintain high prices, but that’s a topic for a separate article.

SURPLUS FACTS

We can now be certain that the hop surplus plaguing the industry today began in 2016. USDA data demonstrate that hop depletion relative to available inventory decreased in recent years (Figure 1). It is clear the 70-year trend regarding the ratio of possession (i.e., ownership) of hops underwent an extreme change beginning in 2016 (Figure 2). That change, and the lack of an immediate reaction to it, created a 54-million-pound (24,494.23 mt) increase in inventory held in the U.S. between 2016 and 2022 (Figure 3). That resulted from a decreases in the annual depletion rate, which also began in 2016 (Figure 4).

Figure 1. Annual U.S. Depletion Relative to Previous U.S. Crop from Previous Year + Available Inventories from Previous Year.

Source: Data Set Calculated from USDA NASS Hop Stocks Report Source Data 2002-2022

Figure 2. Possession of U.S. Inventory in Storage

Source: Data Set Calculated from USDA NASS Hop Stocks Report Source Data 2002-2022

Figure 3. Difference Between Annual U.S. Depletion Relative to Total Available Supply (Crop plus Inventories) Expressed in Pounds.

Source: Data Set Calculated from USDA NASS Hop Stocks Report Source Data 2002-2022

Figure 4. Difference Between Annual U.S. Depletion Relative to Total Available Supply (Crop plus Inventories) Expressed as a Percent.

Source: Data Set Calculated from USDA NASS Hop Stocks Report Source Data 2002-2022

Merchants now admit a massive surplus of American hops exists. In his presentation at the 2023 Hop Growers of America (HGA) convention, Alex Barth estimated the size of that surplus was 35- 40 million pounds (15,875.9 – 18,143.9 mt.). He also estimated annual demand for American hops at 100 million pounds (45,359 mt.). Reportedly, he relied on shipment data versus crop data to arrive at those figures[1]. I did not attend the HGA convention. The PowerPoint files from HGA conventions are available to download here. I don’t question Alex’s estimate, but I did not hear it first-hand. I read it on the Hop Talk™ blog published by CLS Farms, which is worth following. You can find it here. The sources for the shipment data to which Alex referred was not cited. For that reason, we cannot understand the methods used to collect his data and if they are proprietary[2].

According to the USDA, there were 18,954 acres (7,673.7 ha.) more proprietary hop varieties in production in 2022 than in 2016. During the same time, public variety acreage decreased by 6,236 acres (2,524 ha.)[3]. It is reasonable to assume the surplus was caused by the rampant overproduction of proprietary varieties.

THE SURPLUS ULTIMATUM

Based on the USDA data presented above, I do not agree with the suggestion that the current demand for American hops is 100 million pounds (45,359.7 mt.), or that the surplus is 35-40 million pounds. I prefer instead to use 2016 U.S. production of 87,139,600 pounds (39,526.26 mt.) as a starting point as it is based on public data. If you don’t agree, please stick with the numbers that Alex presented. You will see by the end of this article that the difference of 13 million pounds (5,896 mt.) does not affect the severity of the oversupply problem because it is so large.

It was in 2016 that significant changes took place (Figures 1-4). As I mentioned in “Hop Forecast 2023”, the difference between 2016 and 2021 craft beer production was 187,396 barrels (223,451 hl.)[4][5][6]. According to Bart Watson from the Brewers Association, the projected 2022 average hopping rate for craft beer was 1.53 pounds of hops per barrel (4.365 g/hl.)[7]. At that rate, 286,715 pounds (130 mt.) more hops were needed in 2022 than were produced in 2016. That quantity of hops could be produced on 152 additional acres (61.8 ha.) based on the U.S. average yield between 2016 and 2021 of 1,877 pounds per acre (2.1 mt./ha.)[8]. U.S. acreage during that time, however, increased by 8,928 acres (3,614 ha.). Not all of that can be attributed to international demand for American varieties.

That is only the tip of the proverbial iceberg. That 10,000-acre reduction suggested at the HGA convention would align annual supply with annual demand. To be clear … those are acres of trellis that must be removed from the ground so other varieties are not planted in their place for it to be effective. That is within the realm of possibility. The greater problem is the cumulative surplus supply … and how to address it. Based on the figures above and because the annual surplus problem was not resolved when it began, the cumulative surplus in 2023 is massive. Data suggests it includes 54 million pounds (24,494.2 mt.) of undelivered (i.e., unneeded) hops. That number represents the amount U.S. inventories grew between 2016 and 2022 (Figure 3). Their existence, regardless of their contracted status, will depress prices for all hops as they move into the market. They must be sold before the surplus problem can be fixed.

Another way to imagine the problem is that the annual depletion rate relative to the total supply available must return to a level closer to the long-term average (Figure 4). This provides some relief. The 20-year average level of the difference between the annual depletion rate for the current year and the total inventory available following prior harvest is 89.65% (Figure 4). In 2022, it was 77%. That amount expressed as a number in 2022 was 139 million pounds (Figure 3). Why is that good news? Based on the previous 20-year average, a “normal” amount of inventory following harvest is more than double the crop size, which means the goal is not as far away as it could be.

According to the 2022 HGA Statistical Report, the average farmgate value for U.S. hops between 2016 and 2022 was $5.75 per pound ($12.67 per kg.)[9]. The cost of that inventory not including processing costs was $310 million. Despite the billions made in the industry during the previous decade, nobody can afford to throw away or write off $310 million worth of hops. That inventory must work its way through the system. Every merchant understands how that works. That is why whether you believe the actual annual demand for U.S. hops is 87 or 100 million pounds (36,210.7 or 41,621.5 mt.) does not alter what the industry must do to fix the problem.

A massive cumulative surplus undermines the justification for signing forward contracts[10]. International Hop Growers Convention (IHGC) data demonstrate that brewers sign fewer contracts in a surplus[11]. Merchants and farmers will be eager to move older inventory before the new crop arrives creating cheap buying opportunities during the summer months leading up to harvest. It’s evidence of the hop pendulum to which Bart Watson from the Brewers Association referred to in this article swinging back[12].

ANALYSIS

Let’s shift now from facts to my analysis of them regarding what that will mean for the future. You won’t read an analysis of the facts like this anywhere else because these are things people in the hop industry would prefer remain unpublished. I’ll add some opinions and a story from my time as a hop merchant to make it more colorful. If you’ve not already subscribed to this Substack, please consider doing so now.

There are three reasons why the current supply situation is not as simple it appears.

There are stubborn contracted volumes involved. Merchants, farmers … and more importantly their bankers believe that contracted hops belong to the breweries that contracted them. These are assets on their financial statements represented at face value. Breweries don’t always agree whose hops these are. That part comes later. Contracts to American brewers together with inventory are used by banks as collateral to determine limits for lines of credit. Maintaining a reality distortion field regarding their real market value is crucial for the merchant companies holding them. The greater the value of the inventory … the more money they can borrow to finance production and purchases. Most American hop farms and merchants would not be able to maintain the status quo without perpetual lines of credit. No merchant or farmer wants to see the value of existing contracts decline. Bankers want to suspend their disbelief too hoping that the situation will improve before it falls apart.

The collection of surplus varieties in storage may not match brewer needs over the next several years. That slows the movement of the surplus into the market. Even if the varieties are correct, many brewers view older crops as less desirable. Older crops can be of higher quality than the most recent crop. Few brewers understand that. Brewer perception can lead to the need for deep discounts for older product.

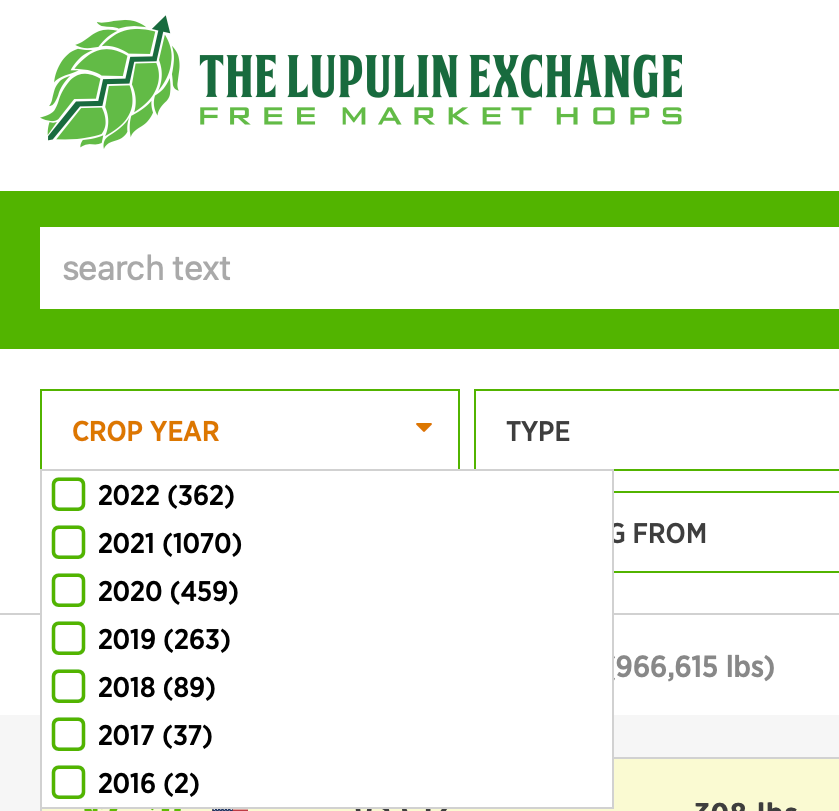

Some of the inventory in storage in the U.S. today dates back seven years. A search on Lupulin Exchange on February 8th revealed 970,839 pounds (440.36 mt.) of inventory available. Some of that was from the 2016 crop (Figure 5). Hops that have been processed and stored under proper conditions for one or two years will not suffer noticeable losses of alpha acid or oil content. Different varieties degrade at different rates[13]. Hops stored for three or more years will begin to show signs of their age. That will change oil and alpha levels from what it was following harvest. Anybody buying inventory more than three years old should do so pending fresh oil and alpha analyses. Gas chromatograph tests can determine remaining essential oil contents[14]. Spectro or HPLC analyses can reveal remaining alpha and beta acid levels[15][16].

Figure 5. Selection of Crop Years Available on Lupulin Exchange on February 8, 2023

Source: Lupulin Exchange[17]

I saw market prices fall significantly below previous contracted prices twice while I was a dealer. Each time, about half of the brewers I was working with honored their contracts. The rest demanded contract renegotiation to reflect the new lower prices available on the spot market. Some said they were not going to honor the contracts at all. Some went dark and didn’t reply to any communications.

The cost of production for U.S. hops has increased due to inflation, but U.S. hop prices have been inflated since 2010. I anticipate American farmers will use inflation to justify increase prices for hops going forward. An accurate cost of production should be determined before inflation is discussed. For more on that, see my previous articles “How Much do Hops Really Cost?” or “Hop Supremacy”. In those articles, I demonstrated how American hop farmers artificially (some might say fraudulently) increased the cost of hops production in 2010 in retaliation for brewer contract cancellations in 2009. How inflation will act together with the effects of the surplus remains to be seen. I expect inflation adjusted season average prices in 2023 to decrease.

Acreage reduction

The additional 54-million-pound (24,494.2 mt.) surplus in inventory in the U.S. represents 28,769 acres (11,647.3 ha.) worth of production[18]. To correct the cumulative oversupply problem in a single year would require idling the entire 28,769 acres (11,647.3 ha.). Together with the 8,776 acres (3,553 ha.) necessary to bring annual supply in line with annual demand, that totals 37,545 acres (15,200 ha.) that must be idled to fix the problem.

Trellis on those 8,776 acres (3,553 ha.) could be idled rather than removed altogether. If they are idled and not removed, any new varieties planted prior to the movement of the cumulative surplus will add to the size of the surplus. Some American farmers will plant public varieties where proprietary varieties were idled. That thought process contributes to the Delayed Surplus Response (DSR) in the hop market[19].

Based on previous cycles, the market does not return to normal until something resembling equilibrium between available supply and demand exists. That will not happen in 2023. It won’t happen by 2025 without cooperation among American hop farmers. The hop industry is filled with opportunists who will exploit a situation to better his own position even at the expense of his neighbor. I know. I was as guilty as any of the rest of them in the past. It’s a normal way of life in the hop industry. They would prefer their neighbor remove acreage or fail altogether than remove an acre from their own farm. They will resort to price competition to get business. Making less money on existing acreage is better to some than making nothing on an acre of ground.

Homo Homini Lupus Est (Man is a Wolf to Another Man)

- Latin Proverb

The relationship between production and price demonstrates how hop cycles have dominated the past 50 years (Figure 6). I believe the current surplus, like others before, will be here for some time to come. The only thing that can prevent this is an American crop shorter than any in recorded history.

Figure 6. U.S. Hop Production and U.S. Season Average Price Adjusted for Inflation to 2022.

Source: Data Set Calculated from USDA NASS Data 1972-2022, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics[20]

American farmers sold their independence to the owners of proprietary varieties (i.e., their competitors) in exchange for the fortunes they’ve made over the past decade. It was a Faustian bargain if there ever was one. For more on the story of Faust see the video below. The mismanagement of those same varieties contributed to the current situation. Now, the owners of those varieties will determine the winners and losers. I anticipate cuts will come from their neighbors’ farms, not their own. Independent farmers will have no recourse … just like Dr. Faust.

Note: I’ve shared this video before in a previous article. It fits the situation so perfectly I had to share it again for those who may not have seen it … plus it’s fun to watch.

Craft brewers were unaware of hop industry politics when they created the proprietary variety monster. They made their own Faustian deals with the devil by signing hop contracts and putting proprietary variety names on their beer labels. If you’re a brewer reading this, I’d like to ask you to share this Substack with some of your brewer friends to increase their awareness of the consequences of using proprietary varieties and how they have affected the prices you pay for hops.

With proprietary variety reduction will come thousands of acres of open trellis. Farmers will try to reassert their independence. If American farmers plant public varieties in 2023, it will signal the return of the hop cycle once again (Figure 7). I expect that is what will happen.

Figure 7. The Hop Cycle Explained

Notes:

The graph above is a general representation of the hop cycle process as it has occurred in the past. It is not intended to be to scale. The time the process takes depends on the size of acreage reduction in each year.

The “YOU ARE HERE” indicates the market position in February 2023

The graph includes an optimistic line denoting increasing future demand. A decrease in hop demand is possible given current trends.

The vertical line represents when annual supply crosses with annual demand. Cumulative surplus does not begin to shrink in a meaningful way prior to this.

Surplus inventory will be used in place of new contracted volume beginning on the left of the vertical line and will be much more pronounced to the right of the line.

Surplus inventory disguises real annual demand to the right of the vertical line.

Prices will weaken the farther right on the graph you go until the surplus is gone.

The graph above depicts why the problem is much bigger than anybody has alluded. The U.S. industry has been told it must aim for equilibrium between annual production and annual demand. That’s not enough to fix the problem. An annual production deficit should be the goal to balance the market. The surplus 54 million pounds (24,494.2 mt.) needs somewhere to go. Believing that it’s the brewers’ problem because the hops are contracted does not fix the problem. The bigger the annual deficit is, the faster the surplus will clear. If you prefer to believe Alex Barth’s numbers from the HGA convention, that’s great[21]. The principle remains the same. While the cumulative surplus of tens of millions of pounds exists, it will stress the market.

Hop merchants and farmers cannot afford that. They need prices to stay high to keep their high-priced contracts intact and to keep brewers from the realization that they have been overpaying for hops for years. They want prices to remain high because they’ve grown accustomed to a great standard of living. That is not how supply and demand operate with regards to price. Even the Encyclopedia Britannica states that an increase in supply leads to lower prices (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Supply Change and its Effect on Price

Source: Encyclopedia Britannica

Surpluses wreak havoc on the hop market. Proprietary variety management was supposed to solve this problem. They failed. American hop acreage and production increased during COVID despite claims to the contrary[22]. Today there is a massive surplus as a result.

“If you lay down with dogs, you wake up with fleas.”

- James Sanford, Garden of Pleasure (1573)

A Brewer Plays His Cards

An American craft brewer once called me upset about his contract. I happened to be in Finland at the time visiting some other brewers. He was unhappy about the prices he was paying for the contracts he signed in 2014. It was 2016 or 2017 and the price of hops had fallen quite a bit from the market high when he bought. He was angry. He demanded I change the price on his contract to reflect the current price. I tried to explain to him it didn’t work like that, that we had contracts with farmers to buy hops that were also expensive and that most of the money he was paying went to the farmer. He didn’t care about that. All he wanted was a lower price. I tried to compromise with him … as merchants do. I suggested the usual things like changing the terms of the contract so he would be contracted for more years and in exchange for that he could get a slightly lower price. I figured we could break even or even take a loss in the short term and make up the profit in a future year. He wasn’t satisfied. Finally, he told me that he and several of his brewer friends were talking about the situation and realized that their contracts were just the right size … what I would now call a sweet zone for brewers. The contract was large enough to make a difference to the brewer if he saved some money. It wasn’t large enough, however, for me to go through the trouble of hiring a lawyer to go after him if he disappeared. If I remember correctly, there was about $10,000 profit on his contract, which was in total about $50,000. That’s what he said he would do if he didn’t get what he wanted, disappear. I told him I’d have to think about his “offer”. We agreed to chat again later. Unfortunately, he was right. A retainer fee for a lawyer would be at least $10,000. Chasing that brewer down would be something that would take years and tens of thousands more dollars to do successfully. Even then, there would be no guarantee he would have to perform on that contract (more on that in another story). I have a feeling this is a problem big hop merchants like Yakima Chief Hops®, John I. Haas or Steiner haven’t had to deal with as often as their smaller competitors. Some brewers see their relationship with a smaller merchant as expendable. They are more afraid to burn a bridge with a larger supplier because there are fewer of them. Proprietary varieties isolated to one merchant have only strengthened their hand. The rules of the game are different for smaller merchants. That’s ironic considering craft brewers are supposed to be for the little guy. That’s the way it is with a surprising number of them. That brewer ultimately compromised … a bit. We compromised more. He got most of what he wanted because, in the end, we had no other choice. He was not the last brewer to use that threat.

That balance of power can change if craft brewers demand a return to public varieties like Cascade, Centennial and Chinook. Craft brewers can bring back market-oriented prices by choosing public varieties instead of chasing the latest and newest proprietary varieties. Now is a difficult time to address the problem. Planting hops in 2023 though is like drilling holes in a sinking boat. It prolongs the surplus. In the past, breweries that had contracts that did not specify delivery dates, combined older expensive contracted proprietary inventory with newly planted cheaper public varieties to lower costs over time. I know a brewery that was still taking their 2008 inventory in 2015. It’s a dirty trick, but … “it’s just business” … right?

The dilemma the industry faces is that discounting old inventory doesn’t increase demand. Brewers don’t use more hops just because they are cheap (demand is inelastic and not price sensitive) [23]. Low prices increase sales. Those purchases satisfy future demand or displace other more expensive purchases. There is no easy way forward.

“If You’re Going Through Hell, Keep Going.”

- Winston Churchill

Thank you for taking the time to read this article. I hope you found some value in it. If you did, it would be great if you could share that value with a friend and spread the word. If you’ve not already subscribed, please consider doing that today.

[1] https://www.hoptalk.live/post/too-many-hops-10000-acre-cut-needed-says-barth

[2] My analyses here and elsewhere rely on publicly available USDA NASS data or calculations made using them. I will always cite my sources so you can look at the original data and reach your own conclusions if you don’t agree with mine. I am not claiming that simply due to the citations my conclusions are any better or worse than Alex’s. There is just more clarity regarding the source of the data I use.

[3] USDA NASS National Hop Report. Available at: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Washington/Publications/Hops/index.php

[4] The most current numbers available at the time of this writing

[5] https://www.ttb.gov/beer/statistics

[6] https://www.brewersassociation.org/statistics-and-data/national-beer-stats/

[7] https://americanhopconvention.org/assets/img/misc/Brewer-Panel-Bart-Watson.pdf

[8] https://www.usahops.org/enthusiasts/stats.html

[9] https://www.usahops.org/enthusiasts/stats.html

[10] https://www.crosbyhops.com/news-blog/blog/hop-contracting-is-changing

[11] http://www.hmelj-giz.si/ihgc/act.htm

[12] https://www.brewersassociation.org/insights/the-hop-pendulum-a-history-of-the-american-hops-market/

[13] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36230176/

[14] https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jf60151a010

[15] https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ed1010536

[16] https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ed085p954

[17] Lupulin Exchange: https://lupulinexchange.com/listings?q=&a=true&SortBy=0

[18] Based on the 2016-2021 average U.S. yield of 1,887 pounds per acre.

[19] MacKinnon D, Pavlovič M. The delayed surplus response for hops related to market dynamics. Agric. Econ. - Czech. 2022;68(8):293-298. doi: 10.17221/156/2022-AGRICECON.

[20] https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm

[21] As a reminder, he suggested there is a surplus of 40 million pounds and an annual demand for U.S. hops of 100 million pounds. The acreage reduction numbers necessary will change.

[22] https://www.yakimaherald.com/news/local/hop-growers-make-changes-adjust-acreage-in-response-to-covid-19-pandemic/article_64c56709-9fca-513f-8b59-73095458b508.html

[23] https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/012915/what-difference-between-inelasticity-and-elasticity-demand.asp