Throughout history, farmers have struggled with prices[1][2][3][4][5]. Hop farmers share that DNA. Twenty years ago, when I was director of Hop Growers of America, prices were at their lowest point in generations (Figure 2). Hop farmers and merchants were at the mercy of a macro brewer oligopsony that dictated prices. Those years set the bar for low hop prices. The hop market in 2022 is quite different. According to Hop Growers of America, American hops in 2022 were worth more than in any time recent history[6] (Figure 1). Despite the highest prices in over 70 years, last time I ran into American hop farmers at Drinktec, they complained about prices. I’m reminded of the fable of the boy who cried wolf.

Figure 1. U.S. Season Average Prices 1948-2020 Adjusted for Inflation.

Source: USDA NASS

Figure 2. U.S. Season Average Prices and Total Crop Value 2011 – 2021.

USDA data demonstrate that you must go back to World War II to find something resembling the current price distortion (Figure 1). That’s significant. It means something on the scale of the supply disruption created by World War II has happened in the hop industry during the past 10 years.

The Hop Oligopoly

The hop merchant trade concentrated into a powerful oligopoly during the past 20-30 years through mergers and acquisitions. Oligopolies are characterized by a limited number of firms with substantial influence, significant barriers to entry and tacit collusion[7]. For the future when today’s industry players have been long forgotten, those firms are commonly thought to be Yakima Chief Hops®, BarthHaas® and Hopsteiner. Since these companies are privately owned, data regarding market share is not available[8].I would add the German farmer collective marketing firm, HVG, to that list. Although they limit themselves to German hop products, their global reach and involvement in infrastructure projects makes them a candidate for this group. To be clear, there’s nothing perceived to be wrong with large oligopolies controlling industries in today’s regulatory environment. This is not necessarily good for the consumer as oligopolies typically result in higher prices[9].

One example of the hop oligopoly is its control over processing capacity. Few farms have cold storage or pellets mills that can process hops into pellets. Ownership of large-scale extraction facilities, however, is much more limited[10][11][12][13][14]. According to the “2021 HopSteiner Guidelines for Hop Buying”, extracted hop products represented an estimated 26.4% of global hop usage (Figure 3)[15]. The few entities controlling extraction have a tight grip on that market. While that is significant, there is a more tightly controlled market segment that makes the oligopoly over hop extraction pale by comparison.

Figure 3. Worldwide Use of Hop Extract

Growing Power

Hops enjoy an inelastic demand; in that they are necessary for beer production. They have long suffered from an elastic supply, which has resulted in boom-and-bust price cycles. The merchant oligopoly, tacit collusion and price leadership to which I referred in my previous article, “Who Sets Hop Prices and How?”, causes prices for American hops move in concert. An uncoordinated but efficient farmer/merchant information network enables market awareness for every participant … if they participate.

The American hop market may appear like perfect competition[16]. Once upon a time, it was. Prior to soaring demand for branded proprietary hop varieties, any merchant had the opportunity to offer similar products at competitive prices or terms. Hop brands like Cascade, Centennial and Chinook on which the craft beer industry was built were public, not centrally controlled and available for anybody produce or sell. Independent farmers ensured competitive prices were available. No more.

Overwhelming demand by craft brewers for proprietary aroma varieties enabled the owners of those varieties to accumulate and concentrate their power and influence. Licensing production agreements purged farmer independence from the supply side. They centralized pricing, planting and sales decisions on their varieties[17]. Once worldwide demand for their products was established, they limited direct access to these varieties to supply chain partners.

Over the past decade, proprietary hop supply has been managed so well that surpluses have not appeared. U.S. patent law encourages this type of brand management[18]. When hop supply can be managed, higher average prices are the result (Figure 2). That was the outcome American farmers sought when they regulated the supply available to the market in the 20th century three times using Federal Marketing Orders[19]. Those efforts failed due to the inability of the orders to enforce their mandates. Enter proprietary varieties and Intellectual Property (IP) rights.

The Congressional Research Service determined that IP rights enable the patent holder (or her licensees) to charge higher-than-competitive prices for goods because the patent holder is shielded from competition[20]. Rising season average prices reported by the USDA suggest this is true (Figure 1). The U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) defends monopoly power and monopolistic pricing as an important element of the free-market system[21].

Farmers lacking intellectual property have traded their independence for short-term profit and the perception of security. If the current trend away from public varieties continues, one possible outcome is that these farms will struggle to survive when craft brewers strive for greater efficiency. I will elaborate on that in my next article around the middle of January 2023.

Increasing Concentration

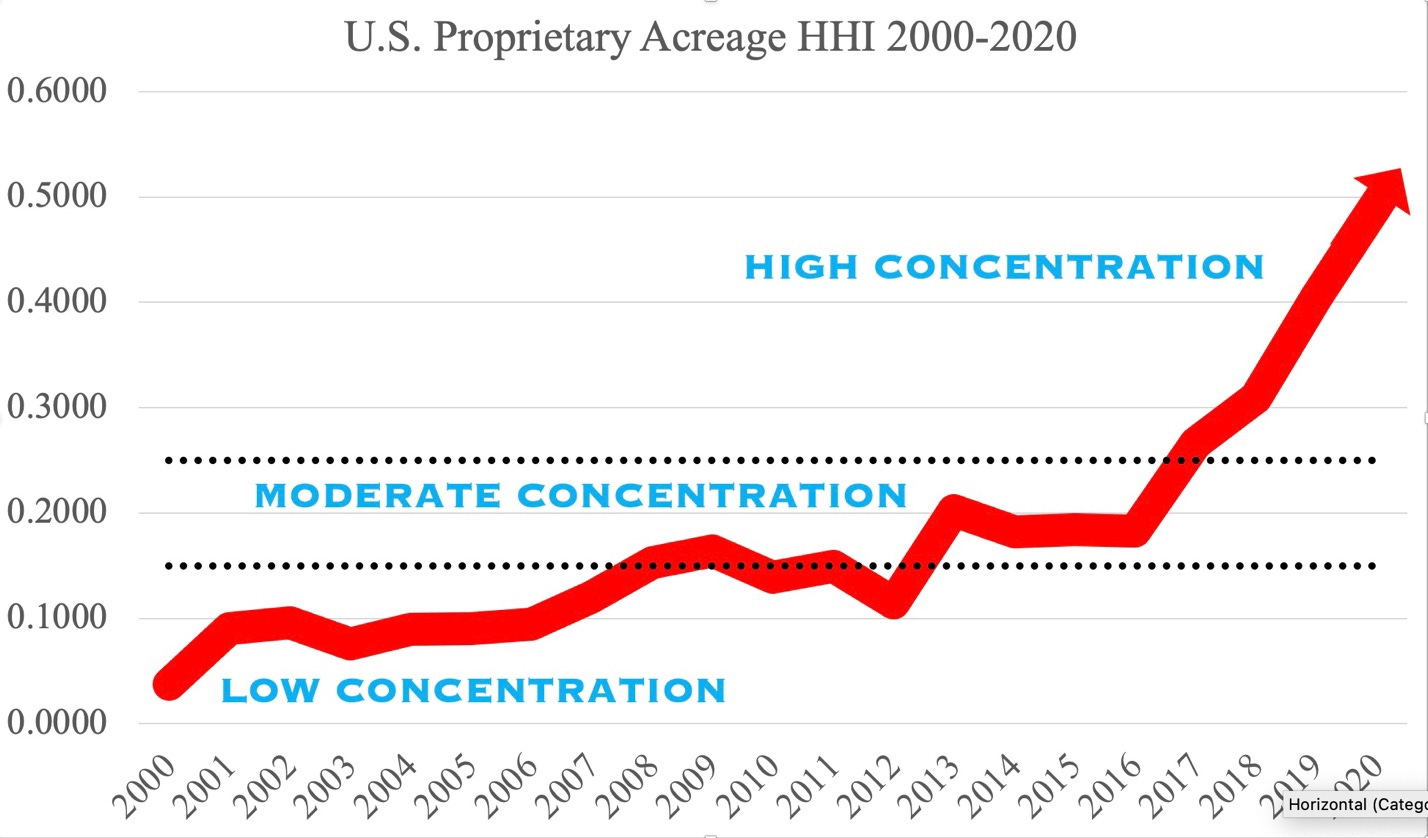

Changes in market concentration of proprietary varieties may be measured using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index[22](HHI) (Figure 4). A low market concentration represents a free market where many players compete for market share. A high market concentration represents the opposite, a market in which few players compete for market share. Concentration should not be confused with competition. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) states that high market concentration does not represent the level of competition within a sector. The players in a highly concentrated markets may still be competitive with one another. High market concentration, rather, is an indicator of changing market structure and power[23]. The degree to which market concentration has increased in recent years, could be the explanation for the price levels not seen since the 1940s. The industry appears as aggressively competitive today as ever despite the increased market concentration. Many market participants continue to act as if the market is a zero-sum game.

Figure 4. Herfindahl-Hirschman Index of U.S. Proprietary Hop Variety Acreage 2000-2020

Source: UDSA NASS National Hop Report data 2000-2020

Note: Market concentration represents proprietary variety competition for acreage, which is, in the opinion of the author, the scarcest and most valuable resource in the industry.

The New Formula

To create the graph above, I grouped the acreage of proprietary varieties by ownership as reported by the USDA. That is possible due to the intellectual property attached to patented and trademarked varieties. Why acreage and not sales? Who owns the acreage on which the varieties are produced is irrelevant in the proprietary world. More acreage may be more of a liability and vulnerability rather than a symbol of power strength and independence as it once was. Via proprietary varieties, an entity can control acreage without owning it. That entity is the master over those who merely produce. Licensing agreements for most proprietary varieties are so strict, farmers have become the production arm of the entities that own the varieties they produce. Those who have not yet recognized their junior status and their vulnerability will notice during the next contraction in demand for hops.

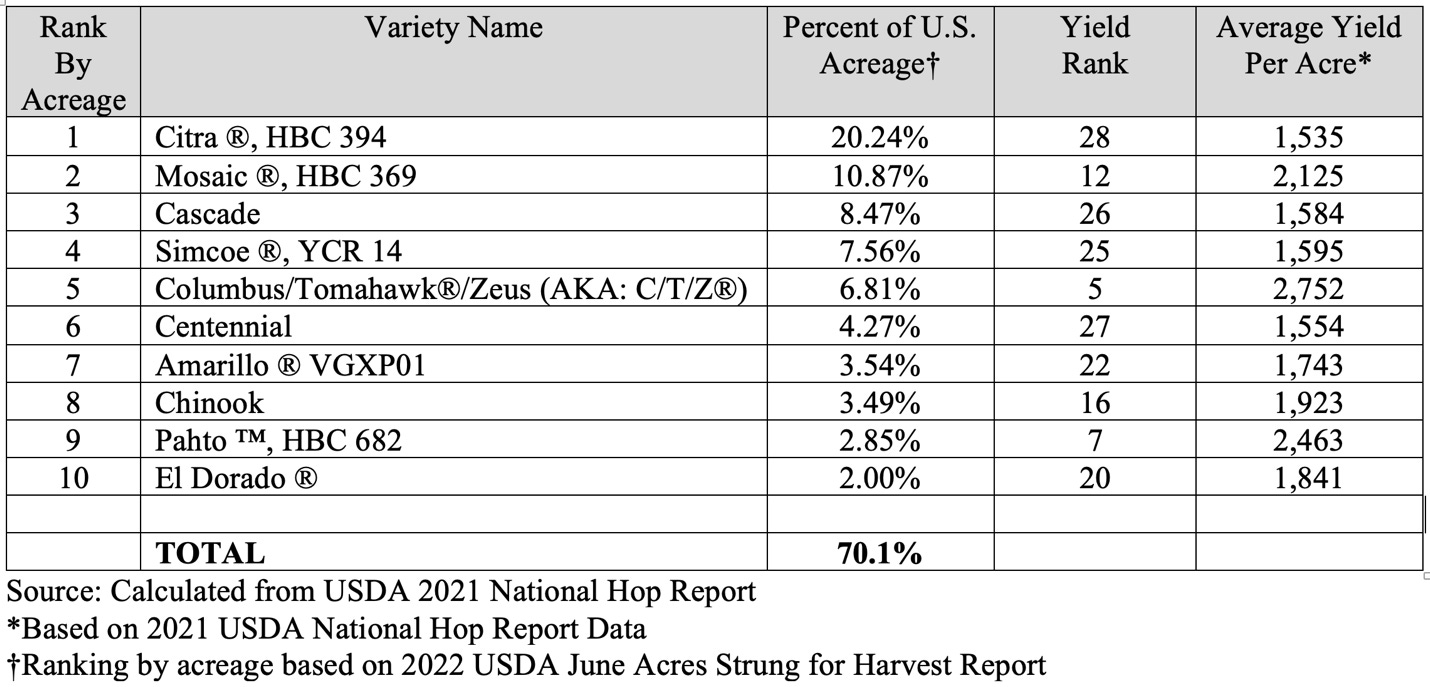

The Hop Breeding Company (HBC) is a joint venture between John I. Haas and Yakima Chief Ranches[24]. They enjoy a significant first-mover advantage in the proprietary aroma variety market segment. The company has become the most influential entity in the industry. They are the clear market leader with such varieties as Citra ®, HBC 394, Mosaic ®, HBC 369 and Simcoe ®, YCR 14, three of the four most widely planted varieties (Figure 5)[25]. If you want one of those varieties, you can’t buy it from the farmer[26]. Instead you need to interact with the duopoly formed by the hop merchant companies that share common ownership with the HBC (i.e., John I. Haas[27][28] (owned in part by BarthHaas®[29]) or Yakima Chief Hops® (linked by the common ownership of the Smith, Carpenter and Perrault families[30][31])). The owners of these companies are the industry’s oligarchs. More on them in a future article. If you’re not a brewer that purchases large volumes of hops, you’ll likely find yourself dealing with members of their respective global supply chains that handle the smaller orders. If you’re persona non grata (i.e., a competing hop merchant), you will be relegated to secondary and tertiary markets. Seldom are prices there competitive. That’s the point.

USDA data revealed HBC varieties represented over 50 percent of U.S. hop acreage in 2020[32][33]. That number declined slightly in 2021. They have are varieties that do not yet meet the USDA criteria for independent reporting not yet listed publicly, which assures they still likely enjoy influence over 50% of U.S. hop acreage. They are not alone. Four other companies influence an additional 20% of U.S. hop acreage[34]. There are several companies whose entire proprietary variety effort does not meet the USDA criteria for independent reporting. We cannot know their influence except through word of mouth. Such a high market concentration in the hands of so few decision makers with a farmer friendly agenda enabled steadily increasing prices during the past decade (Figure 2).

Figure 5. Top 10 U.S. Varieties by Acreage in 2022.

The Cost Narrative

There must be some logic behind the price increases. The oft mentioned invisible hand about which Adam Smith wrote about in his 1776 book, The Wealth of Nations, might bring some vision of supply and demand to mind. In the hop industry, demand represents an opportunity. Without control over supply, it is short lived. American hop farmers demonstrated in 1980, 2007 and 2008 their ability to oversupply any perceived demand in an unregulated market. Proprietary varieties eliminate that problem. The tight control from production and sales licensing agreements is crucial. Managing the supply side of the situation is allowed through the enforcement of IP rights affects hop prices. There must, however, still be a way to justify the cost per pound to the masses. In theory, yield should affect cost. Enter the WSU Cost of Production Survey, something I wrote about in my article, “How Much Do U.S. Hops Really Cost?”.

In that article, I revealed how American hop farmers changed the methods by which they had calculated their cost of production in 2010. The result was a cost of production that outpaced inflation (Figure 6)[35]. There’s a little more to the story.

Figure 6. WSU Cost of Hop Production Survey Results 1999 – 2020.

Source: 1999, 2004, 2010, 2015 and 2020 WSU Cost of Hop Production Surveys

The intent of the survey remained the same over the years. It is to calculate a “breakeven” price for farmers. The semantics of which imply that without receiving that price farmers are losing money. The 2020 report shares how to calculate the breakeven price, “Break-even return is calculated as: cost divided by yield during mature production.[36]” The breakeven price for each variety therefore may be calculated using the data from the report together with average yield data reported by the USDA. That seems straightforward.

In 2010 WSU Cost of Production Survey, however, the methods for amortizing and depreciating assets changed from methods that had been used for decades prior. The 2010 report explained the change using the following rationale.

“… things are currently so volatile that growers can no longer count on being able to amortize the cost of planting along with a new trellis and drip irrigation system over more than a few years. Under the current situation, some growers who thought they had a five-year contract to amortize establishment costs are being asked to give up those contracts in as little as two years.”[37]

Evidence of the scale of the contract abandonment is visible in International Hop Growers Convention (IHGC) sold ahead data from 2009 and 2010[38]. It was a difficult time. Abandoned alpha acreage facilitated the transition to aroma hops at lower expense enabling the boom that continues to this day. The language explaining the 2010 changes to the cost of production survey calculations, however, could be misinterpreted as farmers taking revenge against the brewing industry for cancelled contracts. The new depreciation methods used in the 2010 survey remained in place in 2015 and 2020[39]. The hop world in 2022 is quite different than it was in 2010. Statistics published by the USDA and Hop Growers of America reflect that. Season average hop prices have soared from $3.14 per pound in 2011 to $5.76 per pound in 2021 (Figure 1). American hop acreage has doubled during that same time according to the USDA. Hops are contracted at high levels according to IHGC reports. Why haven’t the methods for calculating the cost of production reverted to their pre 2010 methods in response?

What if we applied the methods used prior to 2010[40] to the 2020 budget (Figure 7)? As you can see below, there is a difference from the alleged 2020 cost of production of 21%. In other words, when the 2004 depreciation methods were applied to 2020 budget numbers, there was a decrease in the alleged cost of production of $2,853.03 per acre ($7,046.98 per hectare),[41].

Figure 7. Depreciation methods from pre-2010 WSU Survey applied to the 2020 WSU Survey

Follow the Money

Does the WSU cost survey affect the price discovery process? We can infer that farmers perceive the survey provides value. Why else would the industry conduct the survey every five years for decades? If the survey exists to anchor price discussions at a higher level, that alone would be valuable although the effect might be difficult to calculate. Anchoring is a powerful heuristic. I can only speak from my experience as a merchant. Those cost of production numbers affected discussions I had with the farmers from whom I bought hops. I don’t recall anybody saying, “I need x dollars per pound because the WSU cost said so.” Farmers often claimed they “needed” a price that was in line with the reported WSU cost of production survey. I’ve always been sympathetic to the farmer cause. Perhaps I allowed myself to be influenced by farmer claims more than other hop merchants. If that’s the case, I can accept that. Perhaps other merchants knew not to believe farmer claims regarding their cost of production. The prices I paid farmers for hops, however, were often in line with the going rate.

No hop producer interested in increasing his revenue has an incentive to alter an incorrect perception of the industry cost of production. Doing so might reveal the means used to inflate them in the first place. The largest hop merchants, or their owners, produce hops. Hop producers run the industry organizations. It’s clear where their loyalties lie.

Who is looking out for the brewer? Nobody. He is left to decipher truth from fiction. Many of today’s craft brewers were not in the industry before 2010. Are they aware how things have changed? That’s not likely … if they even knew where to look there in the first place.

"Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.

Great men are almost always bad men."

- Lord Acton in an 1887 letter to Bishop Mandell Creighton[42]

Is Something Rotten in the State of Denmark?

The method used by the hop industry is referred to as Over The Counter (OTC) trading[43]. The industry is too small to generate the necessary liquidity for smooth trading on a public exchange. The result is the market lacks the transparency of an exchange-traded commodity. Claims to the contrary are propaganda.

The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) strives to protect consumers from artificially high prices as the result of market manipulation[44]. Back in 2011, under the Dodd-Frank Act, the CFTC adopted two rules to prohibit fraud and manipulation … or even attempted fraud and manipulation … in connection with any swap, commodity contract for sale in interstate commerce or futures contract on or subject to the rules of a registered exchange[45].

The Dodd-Frank Act established a set of criteria by which manipulative or deceptive activity may be evaluated[46]. One of them, for example, prohibits: "false or misleading or inaccurate report concerning crop or market information or conditions that affect or tend to affect the price". The Act says fraud or manipulation, or even attempted fraud and manipulation is a felony. Fines seem a much more common punishment than prison time for those found guilty[47][48]. I don’t know if the Dodd-Frank Act or CFTC regulations applies to the hop industry[49]. It seems they’re more focused on Wall Street and the financial industries. I don’t know if anybody would consider the changes somebody made to the WSU Cost of Production Survey in 2010 significant. Perhaps for the same reason hops are not traded on an exchange, nobody will even care about events in the hop industry. Could it be too small to be relevant?

Questions

After writing this article, I’m left with a lot of questions that require more investigation. Has the true cost of hop production intentionally been misrepresented? Is it an oversight that more recent cost of production surveys continues to use the 2010 depreciation method? Has any of this had any effect on American hop prices? Have thousands of brewers and tens of millions of beer drinkers paid inflated hop prices for over a decade as a result? The total crop value of the U.S. hop industry between 2011 and 2021 (Figure 2) totals $4.8 billion. That doesn’t include the effect after processing and storage and merchant margins. It seems like a 21% discount over time would add up to some real money. Maybe brewers don’t mind high prices as long as they’re able to make money.

European hop farmers dream of the high prices American hop farmers have received for over a decade. Are those prices the natural result of a hop merchant oligopoly? Could they be a result of demand for the special proprietary varieties produced in the U.S.? Is there something else affecting price? Or … is it a combination of all of the above?

It’s wonderful that craft brewers want to pay a fair price to support hop farmers who they believe are struggling. Inflation will be driving hop prices higher in 2023 and beyond. Craft brewers might want to evaluate the point from which future price increases will begin to better understand if they’re being played. Will anybody take the time?

Once again, I would like to thank you for reading this article. I enjoy the process of writing them and I sincerely hope you enjoy reading them. I hope you found some value in the things I’ve written here. If you did, please consider sharing it with somebody else you think might find it interesting. If you’ve not yet subscribed to the MacKinnon Report, please consider doing that as well.

[1] https://economics.yale.edu/sites/default/files/yale_money-prices-markets.pdf

[2] https://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-economics-of-american-farm-unrest-1865-1900/

[3] https://www.bamb.co.bw/farmers-often-complain-bamb-prices-are-low-why

[4] https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/bd/economy/farmers-complain-over-influx-of-cheap-tanzania-produce-at-border-market-2144448

[5] https://time.com/5736789/small-american-farmers-debt-crisis-extinction/

[6] The Hop Growers of America 2021 Statistical Packet: https://www.usahops.org/img/blog_pdf/405.pdf

[7] https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/121514/what-are-some-current-examples-oligopolies.asp

[8] The exception to this case is with Yakima Chief Hops®. Former CEO of Yakima Chief Hops®, Steve Carpenter, in an interview with Forbes, mentioned that sales for the company in 2019 were 40 million pounds (18,143 MT) of hops. The interview may be found at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/kennygould/2019/10/25/learn-about-hops-with-steve-carpenter-5th-generation-farmer-and-former-yakima-chief-hops-ceo/?sh=6110a80e73cb If Steve’s figure was accurate, that would be 14.2% of the 280 million pounds of hops produced in the world according to the IHGC November 11, 2019 Economic Commission summary report. That report is available at: http://www.hmelj-giz.si/ihgc/doc/2019%20NOV%20IHGC%20EC%20Report.pdf

[9] https://www.rhsmith.umd.edu/research/america-has-oligopoly-problem

[10] https://www.natex.at/about-us/project-references/worlds-largest-hops-extraction-plant/

[11] https://www.craftbrewingbusiness.com/ingredients/watch-this-deep-dive-video-on-yakima-chiefs-co2-hop-extract/

[12] https://www.hvg-germany.de/en/history/

[13] https://www.inside.beer/news/detail/germany-the-worlds-largest-hops-extraction-plant-goes-into-operation/

[14] https://www.hopsteiner.com/processing-and-logistics/

[15] The HopSteiner 2021 Guidelines: https://www.hopsteiner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Guidelines_2021_online.pdf

[16] https://kstatelibraries.pressbooks.pub/economicsoffoodandag/chapter/__unknown__-5/

[17] There are a few exceptions to this, producers who are allowed to sell directly. Their impact on the market is insignificant.

[18] https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6456&context=penn_law_review

[19] https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2003/07/28/03-19127/hops-produced-in-washington-oregon-idaho-and-california-hearing-on-proposed-marketing-agreement-and

[20] https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46679

[21] https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/public_statements/distinguishing-unilateral-conduct-aggressive-competition/060403tokyoamericancenter_0.pdf

[22]The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) is a method to measure market concentration, or to evaluate one competitor's position relative to another. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) has used the HHI since 1982 to measure market concentration. It may be used to determine the appropriateness of mergers and acquisitions.

[23] From the OECD Directorate for Financial and Enterprise Affairs Competition Committee, Executive Summary of the hearing on Market Concentration 6-8 June 2018: https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/M(2018)1/ANN7/FINAL/en/pdf

[24] The Hop Breeding Company website: https://www.hopbreeding.com

[25] USDA NASS 2022 June Hop Acreage Strung for Harvest report: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Regional_Office/Northwest/includes/Publications/Hops/2022/HOP_06.pdf

[26] There are a couple minor exceptions to this rule, but their direct sales do not influence the market significantly.

[27] https://www.johnihaas.com/about-us/

https://www.hopbreeding.com/#about

[29] https://www.barthhaasx.com/about-us

[30] https://www.yakimachiefranches.com/about/

[31] https://careers.yakimachief.com/our-heritage/

[32] The Hop Breeding Company website: https://www.hopbreeding.com

[33] I will make new calculations regarding variety ownership and update these graphs and tables once the USDA NASS National Hop Report data becomes available later this month.

[34]https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Regional_Office/Northwest/includes/Publications/Hops/2021/hops1221.pdf

[35] In the 2004 WSU Cost of production survey, amortization was calculated at 7- or 21-year periods. Three categories: 1) Machinery and building annual replacement cost, 2) Interest cost of fixed capital, and 3) Amortized establishment costs represent $401 of a total cost of production of $3542.51 (11%).

From the 2020 WSU Cost of production survey, the three similar categories called: Depreciation cost of fixed capital, Interest cost of fixed capital, and Amortized establishment cost equal $4,347.78 of a total cost of production of $13,588.66. That equal 32% of total costs

[36] The 2020 WSU Cost of Production Survey may be found at the following URL: https://www.usahops.org/growers/cost-of-production.html

[37]The 2010 WSU Cost of Production Survey: https://pubs.extension.wsu.edu/2010-estimated-cost-of-producing-hops-in-the-yakima-valley-washington-state

[38] http://www.hmelj-giz.si/ihgc/act.htm

[39]The 2020 WSU Cost of Production Survey: https://www.usahops.org/cabinet/data/TB38E%20Conventional%20and%20Organic%20Hops%20Enterprise%20Budget%20in%20PNW.pdf

[40] The 2004 WSU Cost of Production Survey was the survey that preceded the 2010 survey.

[41] If we apply the methods for calculating amortization and depreciation used prior to 2010, totals for those categories in 2020 equal $1,494.75 per acre. That is $2,853.03 (21%) per acre less than current claims. That results in a 2020 breakeven cost of production of $10,735.63 per acre … not $13,588.66. These methods, when applied to 2021 USDA average yields for each of the top 10 varieties, reveals a new “breakeven” cost per pound.

[42] https://www.phrases.org.uk/meanings/absolute-power-corrupts-absolutely.html

[43] https://www.investopedia.com/terms/o/otc.asp

[44] https://www.cftc.gov/PressRoom/PressReleases/8534-22

[45] https://www.wilmerhale.com/insights/publications/the-commodity-futures-trading-commission-issues-sweeping-new-rules-to-prohibit-fraud-july-28-2011

[46] https://www.wilmerhale.com/insights/publications/the-commodity-futures-trading-commission-issues-sweeping-new-rules-to-prohibit-fraud-july-28-2011

Specifically, Rule 180.1(a) makes it unlawful to:

(i) use or employ, or attempt to use or employ, any "manipulative device, scheme or artifice to defraud";

(ii) make, or attempt to make, any "untrue or misleading statement of a material fact or to omit to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made not untrue or misleading";

(iii) engage, or attempt to engage, in any "act, practice, or course of business, which operates or would operate as a fraud or deceit upon any person"; or

(iv) knowingly or recklessly deliver or cause to be delivered a "false or misleading or inaccurate report concerning crop or market information or conditions that affect or tend to affect the price" of a commodity.

[47] https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/bank-nova-scotia-agrees-pay-604-million-connection-commodities-price-manipulation-scheme

[48] https://www.cftc.gov/PressRoom/PressReleases/8534-22

[49]https://www.cftc.gov/sites/default/files/idc/groups/public/@newsroom/documents/speechandtestimony/aac120607_heitman2.pdf