How Much Do U.S. Hops Really Cost?

How U.S. farmers changed the way they calculate their costs of production.

For those of you who don’t already know, there’s a survey published by Washington State University every five years regarding the cost of hop production. The most recent report is available on the Hop Growers of America web site and is called, "2020 Estimated Cost of Establishing and Producing Hops in the Pacific Northwest". To simplify things, I’ll refer to these reports as the Cost of Production Survey or something similar along with the year they were produced. To put these reports into a historical perspective as I did in my previous article, we need to zoom out to compare surveys from the past with the 2020 survey to see the differences. To better understand the current cost of production narrative and put it into perspective, we will go back to 1999[1].

According to the Brewers Association, 7,434 of the 9,247 brewers in the U.S. (as of 2021) were not in business before 2010[2]. Their limited experience is with an industry dominated by proprietary varieties. A broader perspective will show how the methods for calculating the cost of production in the U.S. were manipulated since 1999.

WSU Cost of Production Survey Results

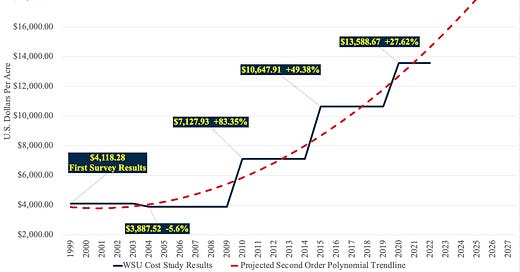

The cost of hop production has not always increased from survey to survey. The cost of production reported by the 2004 WSU survey, decreased 5.6% from 1999. Between 2004 and 2020, according to the survey, costs increased 249 percent.If the methods for analysis used since 2010 continue, considering inflation and higher interest rates, the next survey results will likely claim the cost to produce hops in the U.S. is $18,000 – 20,000 per acre ($44,460-$49,400 per hectare) (Figure 1). If true, combined assuming an average yield of 1900 pounds per acre (2.12 MT/hectare)[3] a 2025 survey would recommend a breakeven price to the farmer of $10.52 per pound ($23.2 per kilo). In this article, I’ll explain the methods used that ensure prices will continue to increase faster than the rate of inflation.

Figure 1: WSU Cost of Production Survey Results 1999-2020 and Projected Trendline Through 2027.

Source: 1999, 2004, 2010, 2015 and 2020 WSU Cost of Production Surveys

Economic, Financial and Enterprise Budgets

In the 1999 and 2004 surveys, a five-page description of the difference between an economic and financial budget was explained[4]. The term “economic budget” was mentioned in the 2010 report to refer to a budget that included non-cash costs like depreciation. There was less attention to this idea in 2010 than in previous reports. Instead, the description appeared throughout the report[5]. In the 2015 report, the term “economic budget” was missing and “opportunity cost”, was mentioned once. The 2015 survey transitioned to the term “enterprise budget” to represent all production costs, financial and non-cash[6].

By 2020, the term “opportunity cost” appeared in two footnotes in favor of the more ambiguous “enterprise budget” that is all encompassing. The term opportunity cost represents lost profits a person or entity incurs by choosing one alternative over another[7]. The use of “opportunity cost” exposed the strategy of American farmers to create a budget in which they halve their cake and eat it to (i.e., to receive the profits they lost by choosing to invest in hops over something else … while investing in hops). The changing terms creates the opportunity for greater confusion and ambiguity.

There’s nothing wrong with minimizing risk. That is what the WSU cost of production survey does by incorporating opportunity costs … regardless of the terminology used. It’s hidden in plain view in the report. Anybody reading the document rather than skipping to the section with the breakeven price information will see that a significant portion of the cost of production are non-cash expenses based on current market valuations. This is one of the reasons alleged costs of U.S. hop production increased after 2010 … and why they will continue to increase in the future.

Amortization Costs

The reported cost of depreciation (a.k.a. amortization) affects the recommended breakeven price. I’m not an accountant and neither are most of the people who will read this. For that reason, I’d like to present a definition of amortize from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary[8]:

In the 1999 and 2004 surveys, hop plants were amortized over seven years. Trellis and other fixed expenses were amortized over 21 years. The surveys explained the justification for the seven-year amortization of hop plants by stating,

“Hop plants have a 7-year life due primarily to variety changes.”

They explained the justification for the 21-year amortization of trellis and irrigation by stating,

“Hop poles and trellis systems have a 21-year life.” and,

“A drip irrigation system costs $1,000 per acre to install with a 21-year life.”

These reasons are based on the useful life of the asset. That makes sense. It should be noted that hop plants in many regions around the world can be productive for much longer than seven years if the variety is not changed for another. Trellis has been known to last for much longer than 21 years depending on the climate and treatment used on the poles. The logic of using these lengths of time was established long before the 1999 survey. The 1986 version of the cost of production survey[9] states, “Hop roots have a 10-year life including the establishment year.” and “Hop poles, trellis, etc., have a 20-year life.” These lengths of time coincide with those mentioned in Publication 946 from the U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS)[10].

Changes in 2010:

In the 2010 WSU Cost of Production Survey[11], there were some significant departures from previous methods for calculating costs. The changes were responsible for the rapid increase in the reported cost of production.

The 2010 survey changed the lengths of time over which assets were depreciated (i.e., amortized). The survey provided the following justification,

“… things are currently so volatile that growers can no longer count on being able to amortize the cost of planting along with a new trellis and drip irrigation system over more than a few years. Under the current situation, some growers who thought they had a five-year contract to amortize establishment costs are being asked to give up those contracts in as little as two years.”

The 2010 report changed the expected lifespan from seven and 21 years for hop plants and fixed assets respectively to four years for all assets. The survey explained,

“… the amortized establishment costs comprise the planting costs amortized over 4 years based on the life of hop plants, and trellis and irrigation costs amortized over 4 years based on the assumed life of the trellis and irrigation systems. In both cases, a short term interest of 6% is used.”

The change was, I believe, a knee-jerk reaction to the extreme events of 2006-2010. To sum up that turbulent period, brewers worldwide signed contracts for alpha acid on an unprecedented scale in 2007 and 2008 in response to a perceived shortage. Hop farmers in the U.S. planted 11,533 acres (4,669 hectares) as a result. This created a massive increase in production (Figure 2). Brewers abandoned or renegotiated many of those contracts in 2009 and 2010. By 2011, U.S. acreage was only 422 acres (170 hectares) higher than in 2006[12].

Figure 2: U.S. Hop Production 1948-2022

Source: BarthHaas Reports 1948-2021[13], Douglas MacKinnon Estimate of 2022 U.S. Production

The people influencing the WSU cost of production survey methodology changed the parameters so future prices could compensate for any similar situations that might arise in the future. Such a situation had not occurred by 2015 … or by 2020. Due to demand for proprietary aroma varieties and the contracts necessary to purchase them, the industry arguably became more stable after 2010 (Figure 3). Contracting rates after 2010 were higher and more stable than those between prior to 2010[14]. The survey neglected to return its previous methods for amortization. In fact, the 2015 and 2020 surveys doubled down when they changed the amortization period from four to five years with no explanation other than, “Hop plants have a 5-year life.” It’s a strategy that appears to be based on revenge.

Figure 3. Forward Contract Rates in 2016 for U.S. Hops for years 2016-2021

Source: IHGC 2016 Economic Committee Country Reports[15].

There is no method by which the average age of the industry’s assets is tracked for the WSU survey. For the purposes of this survey, every acre of hop trellis is treated like a newly purchased and freshly constructed acre of hop trellis every year. This is due to the use of opportunity costs to calculate cash cost value. To be clear, that is not the opportunity costs of the actual dollars invested by the farmer in the assets in question at the time of the investment. It is calculated on the most recent estimated book value of those assets. The cost of production will increase together with the value of the assets used to produce hops (i.e., land, equipment, machinery) so long as their current value continues to increase.

Establishment Costs

The next item of interest in the cost of production reports is how farmers would like to be reimbursed for the costs to build new hop trellis. In the survey, they call this the establishment costs. As with the amortized expenses mentioned above, in the 2010 survey, these expenses were calculated at a level that would reimburse the farmer over the four years following planting. This, they again claimed, was in line with the expected lifespan of the trellis, irrigation and hop plants. For the 2015 and 2020 surveys, the number of years was changed to five years. There was no explanation for the 25% increase in the life of these assets from 2010.

The issue that applied to amortization affected establishment costs, but with a twist. For the purposes of the survey, establishment costs are calculated at the most current book value. The twist with establishment costs is when they end. It seems they don’t. According to the survey, they should end after five years. The survey does not track the age of acreage or the proportion of new versus old acreage. The result is that amortized establishment costs continue to increase in perpetuity based on the current book value of the newly established acreage … regardless of when the trellis was established.

In the 2020 report, the amortized establishment cost is $2689.43 per acre. That was equal to 19.7% of the reported total $13,588.66 cost of production. It seems reasonable for a farmer to want to be reimbursed for establishment costs if they have built a new hop yard. It seems unreasonable though for the establishment cost reimbursement to continue forever.

Average Yields

When I’ve questioned the rising costs of production in the past, I was told it costs more to produce hops today because aroma varieties yield less per acre than the alpha varieties the U.S. industry used to produce. On the surface, that sounds like a logical explanation. There are a lot more aroma varieties in the U.S. today than there were 10 or 15 years ago. How much yields have change depends on the point at which you start measuring. Average annual yields for the U.S. fluctuate every year (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Average Annual Hop Yield per Acre in the Pacific Northwest

Source: BarthHaas Reports 1948-2021, Douglas MacKinnon Estimate of 2022 U.S. Production

The record low European hop yields of 2022 demonstrate why it’s a good idea to use long-term averages to demonstrate changes over time. To illustrate how hop yields have changed over the past 70 years, I created a more useful five-year average yield for the U.S. (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Five-year Average Hop Yield per Acre in the Pacific Northwest

Source: BarthHaas Reports 1948-2021, Douglas MacKinnon Estimate of 2022 U.S. Production

Using 1999 as a baseline, a measurable difference between the five-year average yields from one survey period to the next is apparent (Figure 6)[16]. Using yield as the sole metric, production in 2020 was 3.69% more efficient than 1999 when costs were significantly lower[17].

Figure 6: Percentage Five-Year Average Hop Yields Have Changed Since the Previous WSU Cost Survey Data.

Source: USDA NASS National Hop Reports 2000-2021

There’s a flaw in this argument though. Average yield figures don’t consider related expenses that differ with changes in varieties. Some alpha varieties are highly susceptible to powdery mildew. They require more expensive and more frequent pesticide applications than some aroma varieties. Aroma varieties in 2022 are dried at lower temperatures than alpha varieties were in the past when yields were higher. These are things that increase costs. The point here though is to debunk the argument that the cost of production has increased due to lower yielding aroma varieties. Fact Check False!

Inflation

The next component of rising costs we will address is inflation. That’s a topic on everybody’s mind in 2022. During the past 23 years, the annual rate of inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) [18] has increased every year except for 2009 (Figure 7).

Figure 7: CPI Annual Inflation Rate 2000-2021.

Source: Macrotrends.net[19]

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the cumulative effect of CPI inflation between the 1999 and 2020 WSU surveys was 55.3%[20][21]. Using CPI to measure inflation, the reported $4,118.28 cost of hop production in 1999 was the equivalent of $6,397.70 in 2020 dollars. For those of you curious about the math, the 2020 reported cost of production is 112% higher than that. Energy inflation is not included in the CPI. The rising cost of energy is on everybody’s mind right now with the situation in Ukraine. Between 1999 and 2020, energy inflation was 30.09%[22]. That would not increase our CPI estimate. Inflation played a role in the increasing cost of hop production. When the inflation effect is removed, we are left with 193.7% of alleged cost increases between 2004 and 2020 unaccounted for.

Lifestyle Inflation

I won’t discuss the legitimacy of the expenses included in the survey and if they are necessary to production. As people become wealthier, they suffer from lifestyle inflation[23]. Their wants become needs. What one person believes he needs to survive another can get along fine without. Today many U.S. farmers pour concrete around picking machines as a method of keeping dust down during harvest. In the past, they used chopped hop waste to accomplish the same goal. Some U.S. hop farmers lease new tractors rather than repairing older equipment as they would have done in the past. Hop poles in fields are straight in every direction. This creates beautiful geometric patterns. In the past, those fields would not have been straight. Everything inside the picking facility is painted prior to harvest and in pristine condition. It’s beautiful. Picking facilities in 2022 are the factory showrooms of the hop industry. Steel cable used on trellis today, as opposed to the wire used in the past, reduces repairs necessary at the end of each season. I could go on.

None of these things materially affect the quality of production. These are examples of wants, not needs. They are represented somewhere in the WSU survey numbers. They are expenses that a farmer can justify to his accountant since thousands of craft brewers visit the Pacific Northwest every summer. There’s nothing wrong with that … if craft brewers understand that that’s what they’re paying for. If they want to see the farms on which their hops are produced and they want a dog and pony show, they should expect to pay more for that. If their priority is high quality hops, American farmers have always produced a very high quality product. That is possible at a much lower price.

When I think of this, I think of an example that involves cars. You can drive from point A to point B in a Volkswagen, or you can drive in a Lamborghini. Both cars are owned by Volkswagen AG[24]. Both will get you where you want to go. The result is the same. You reach point B. The average Lambo is quite a bit more expensive than most other cars. If the purpose of getting from point A to point B is to reach point B, the car in which you arrive is irrelevant. The person driving the Lamborghini has other goals than simply reaching point B.

Credibility

The cost of production survey is published under the auspices of Washington State University (WSU). The WSU moniker confers the appearance of neutrality and credibility to the cost of production survey results. They do a very thorough job putting together the report. It’s nicely done and easy to read. Research is only as good as the data on which it is conducted. “Garbage in garbage out.” as the saying goes.

The data for the WSU cost of production surveys is provided by farmers and funded by a farmer-controlled organization. If those results are bias, it is through no fault of those compiling the data.

The 2020 WSU survey research “… was funded by the Washington Hop Commission”[25].

Data for the study was provided by, “… the Hop Growers of America board members representing Idaho, Michigan, Nebraska, Oregon and Washington.” [26]

The hazards of industry funded research are well documented. A Google search for “funding effect” yields links to studies documenting the conflicts of interest of such a system. The literature suggests that industry-sponsored studies tend to be biased in favor of the sponsor’s products[27]. “Sponsorship bias” also referred to as the “funding effect” or “funding bias” often creates a strong desire to rig the results[28][29]. An American hop farmer providing data for the WSU survey has a conflict of interest. He will benefit if the report recommends higher prices. Farmers are in favor of higher prices[30]. One of the deliverables of the report is, in fact, a recommended breakeven price. Farmers are usually price takers, not price makers[31]. That changed with the growing popularity of proprietary varieties. American hop farmers today don’t feel they have to sign on the dotted line just to sell their hops. Proprietary varieties enable farmers to enjoy a seller’s market every year.

In the 2020 survey, there is a section entitled “Conventional Hops” in which “break-even return required for aroma hops as of 2020 is $8.17 per pound [sic]…”. The report continues, “the break-even return for alpha hops is $7.55 per pound [sic]…” and states that “the total production costs for conventional hops … are estimated at $13,589 per acre” ($33,564 per hectare).

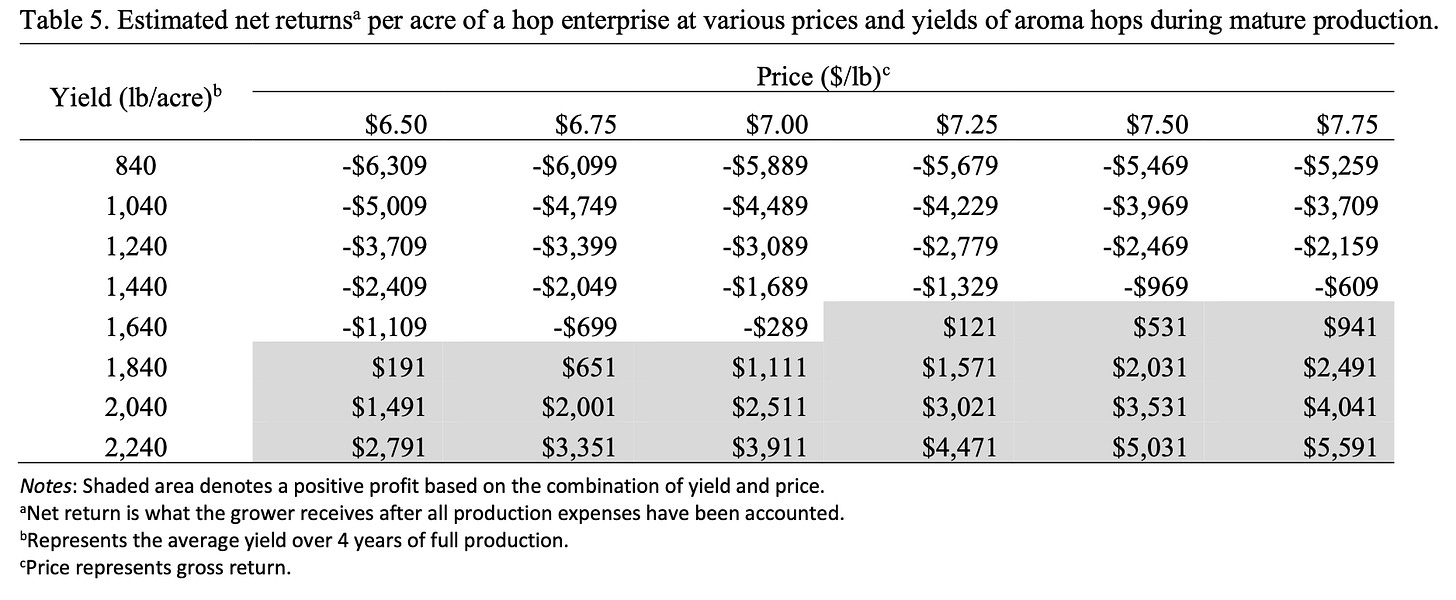

The cost of production survey leaves little doubt. The survey includes a table denoting anticipated profits and losses at various price and yield levels (Figure 8). Its purpose is to suggest prices to purchasers of hops. That is also how it is used. The implication is that anything less than the recommended breakeven price creates an unsustainable situation for the farmer. According to the earlier versions of the WSU surveys, that is not true. A single price cannot represent an industry where some producers have 500 acres and others have thousands. There is no accounting for economies of scale anywhere in the report.

Figure 8: Table from the 2020 WSU Cost of Production Survey Representing Potential Profits and Losses at Various Price and Yield Levels.

The HGA Statistical Packet

Without any reference, the numbers in the table above mean very little. The average yields in the PNW (Figure 9) and the USDA season average prices for the U.S. (Figure 10), demonstrate that season average prices have never reached breakeven levels. Season average price levels are so low, in fact, they do not appear on the breakeven table in the 2020 cost of production survey above (Figure 8). Nevertheless, growers continue to survive and thrive.

Figure 9: Average Hop Yields for Washington, Oregon, Idaho and the U.S. 2012-2021

Source: 2021 Hop Growers of America Statistical Packet[32].

Figure 10: USDA Season Average Prices for Washington, Oregon, Idaho and the U.S. 2011-2021

Source: 2021 Hop Growers of America Statistical Packet[33].

Bias

The literature suggests that industry-sponsored research is more likely than research sponsored by nonprofit organizations including government agencies to yield results consistent with the sponsor’s commercial interests[34]. Has that happened with regards to the U.S. hop industry and the WSU cost of production survey?

The cost of production survey employs a well-known cognitive bias called the Anchoring Bias[35]. By introducing a very high number into the conversation regarding the cost of hop production in the U.S., the survey skews the conversation in that direction. This is due to the tendency for people give a disproportionate amount of credit to the first number mentioned in a negotiation (i.e., the anchoring effect). Thinking Fast and Slow is a great book by Daniel Kahneman that discusses the significance of this and other cognitive biases in much greater detail. Regardless of what real production costs may be, the number $13,588.66 per acre published and seemingly endorsed by WSU is out there. A brewer who does not have information to the contrary is left to assume it is there for a good reason.

What’s the difference?

The line items representing land and infrastructure opportunity costs[36] represent a sizeable portion of the reported cost of production. The two figures in the paragraph above equal $1345.08, or 9.8% of the $13,588.66 per acre ($33,563.99 per hectare). The cost of the amortized establishment cost is $2689.43 per acre, or 19.7% of the reported total $13,588.66 cost of production. That’s a significant portion of the alleged cost of production. That’s three line items from the report. I suspect there are more interesting line items in the surveys, but this article is already long.

There were 33,486 acres (13,557 hectares) of new hop acreage planted in the PNW between 2011 and 2021. There is no accounting of the proportion of newly established acreage. The result is that the cost of production survey is presented in such a way that the reader will infer the breakeven cost of $13,588.66 is the amount of money the farmer needs to survive. In fact, lower prices should be profitable. That depends on how you define profitable. The WSU survey could be a great way to index the cost of hop production to inflation. It could have been a useful producer price index (PPI). Since 2010, however, it seems its purpose has been to accelerate and perpetuate a higher return for the hop industry.

11 Questions to Consider

1) What is the life of a hop yard and irrigation infrastructure? Is five years an accurate estimate?

2) What is the life of hop plants? Is five years an accurate estimate of the number of years a variety remains in the ground before it is changed or becomes unproductive?

3) Is the hop industry in 2022 as risky as the scenario presented in 2010 where farmers could not rely on contracts lasting more than 2-3 years?

4) Is it reasonable for U.S. hop growers to penalize all brewers since 2010 with higher prices for the actions of macro brewers prior to 2010?

5) Is it reasonable for the U.S. farmer to expect a pricing scheme that guarantees zero risk?

6) How are farmers in Europe able to produce hops at prices that are 2-3 times lower than their U.S. counterparts if the costs American farmers claim are necessary?

7) Is the opportunity cost in an enterprise budget an appropriate way to measure the cost of production?

8) Is it reasonable for U.S. hop farmers to receive the opportunity cost of investing the most current book value for every acre of land, for every building, for each piece of machinery and for every piece of equipment on the farm every year?

9) Do brewers understand who supplies the data for these surveys, who funds the research, or the purpose of the budget narrative?

10) Would a range of high and low costs of production across the U.S. industry be more accurate and effective than a single number?

11) Would an alternate survey that sourced production-related costs from different sources provide a useful cost of production estimate, or is the entire idea flawed?

I hope this article created value for you. If you found value in anything you read here, please consider sharing it with somebody who might also find it valuable.

I will never charge for the articles I am posting on Substack. My reward for the time and effort I am investing into them is hearing your feedback … good and bad. I would like to thank all the people who have been sharing the previous articles. It makes a difference.

“And ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free.”

- John 8:32 KJV

Thank you for reading!

[1] This article will use the 1999 WSU Cost of Production survey as a baseline for data.

[2] Brewery account available online at: https://www.brewersassociation.org/statistics-and-data/national-beer-stats/

[3] 1900 pounds per acre was the average hop yield for the U.S. according to the Hop Growers of America Statistical Packet, which can be found at: https://www.usahops.org/enthusiasts/stats.html

[4] Survey Budgets

Earlier versions of the survey took great pains to explain the reasoning behind information they presented. The explanation of the differences between an economic and a financial budget took up five pages in both the 1999 and 2004 surveys. Below are some highlights from Appendix II of the 1999 WSU cost of production survey entitled, “Understanding and Using WSU Hop Enterprise Budgets”.

· “Producers reviewing these budgets most likely will state their own costs are lower than those presented. Furthermore, others outside the industry may question the cost estimates and “breakeven” prices stating, “Since some WSU budgets show producers are operating at a loss, how do they stay in business?” To adequately address these concerns and questions, one must understand the difference between “economic” and “financial” budgets and how an economic budget can be used to develop a financial budget.”

· “WSU enterprise budgets are economic budgets.”

· “To fully understand these hop budgets, one must understand the concepts of opportunity cost and amortized establishment cost.”

· “Since most producers have equity in their farm business and provide labor and management associated with running their operation, in order to determine a given producer’s costs excluding opportunity costs (i.e., financial costs), adjustments must be made to the “economic” hop budgets presented in this bulletin.”

· “Thus, it can be seen why producers who have sizable equity in their farm business can often “survive” at prices below those determined as break-even prices by WSU crop enterprise budgets.”

From the 2004 Report

The 1999 and 2004 reports explain that to make an economic profit farmers must receive the equivalent of what assets they already own could make “in the next best similar risk alternative”. The reports go on to explain, “Thus, the hop enterprise budgets reflect an interest cost on both owned and borrowed capital.” In simple English, that means that a farmer who owes nothing for his land or equipment can, for the purposes of this economic budget, represent the value of those assets as costs as if they were recently purchased.

The U.S. produced 27,731 acres (11,227 hectares) of hops in 2004, the lowest acreage recorded in the past 50 years. By 2021, there were 63,259 acres (25,610 hectares). The value of one acre of bare land in the 2004 report was $3,000. In the 2020 report, that increased to $15,000 per acre. For the purposes of the cost of production survey, every acre in production in 2020 was given the $15,000 per acre value regardless of the price paid for it. The 2020 survey used 4.5% interest on the $15,000 per acre land value … for every acre in production. This contributed $675.00 to the fixed cost portion of the budget. Another fixed cost of $670.08 was added for the “Interest Cost of Fixed Capital”. The calculation pertaining to machines, equipment, shop, office and irrigation infrastructure. These are applied to the entire farm at 2020 values regardless of whether these assets were purchased in 2020 or 1986. Increases in the interest rate by the FED during 2022 will increase this interest expense line item in future surveys.

[5] https://pubs.extension.wsu.edu/2010-estimated-cost-of-producing-hops-in-the-yakima-valley-washington-state

[6] https://abm.extension.colostate.edu/enterprise-budgets/

[7] https://www.investopedia.com/terms/o/opportunitycost.asp

[8] https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/amortize

[9] The 1986 version of the WSU cost of production survey is available at: https://rex.libraries.wsu.edu/view/pdfCoverPage?instCode=01ALLIANCE_WSU&filePid=13332948910001842&download=true

[10] https://www.irs.gov/publications/p946

[11] The “2010 Estimated cost of producing hops in the Yakima Valley, Washington State”, also referred to as the “WSU Cost of Production Survey” is available on the Hop Growers of America web site at: https://pubs.extension.wsu.edu/2010-estimated-cost-of-producing-hops-in-the-yakima-valley-washington-state

[12] USDA NASS National Hop Reports 2006-2011

[13] https://www.barthhaas.com/en/downloads/berichte-broschueren

[14] IHGC Economic Committee Country Reports available at: http://www.hmelj-giz.si/ihgc/act.htm Reports prior to 2010 are no longer publicly available and are password protected for members of the IHGC. Please contact me if you would like to receive a copy of the reports prior to 2010 as I downloaded and saved copies of all IHGC material between before they were made private.

[15] Available at: http://www.hmelj-giz.si/ihgc/activ/apr16.htm

[16] An increase in yields per acre leads to lower costs per pound of hops while decreased yields causes higher costs per pound.

[17] If you want to run this experiment yourself, start with a baseline value in 1999 of $100. Based on the changes between survey years, the 2004 value will be $109.85, the 2010 value will be $118.38, the 2015 value will be $110.39 and the 2020 value will be $103.69.

[18] There are many reasons why the CPI is not the most appropriate unit of measurement for hops. A Producer Price Index (PPI), if one existed, would be more appropriate. A hop-specific PPI does not exist. There isn’t a PPI for an industry related to hops. Using multiple PPIs for unrelated crops would be the only option if a PPI was used. The CPI includes sales and excise taxes whereas PPIs do not. Despite this fact, it is a metric used in the U.S. to report on inflation. As such, I believe it will suffice for the purposes of representing how much more expensive goods and services are in 2022 relative to 1999.

[19] https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/USA/united-states/inflation-rate-cpi

[20] https://data.bls.gov/pdq/SurveyOutputServlet

https://www.usinflationcalculator.com

[22] https://www.in2013dollars.com/Energy/price-inflation/2004-to-2020?amount=100

[23] https://www.investopedia.com/terms/l/lifestyle-inflation.asp

[24] https://www.motortrend.com/news/who-owns-porsche/

[25] The “2020 Estimated costs of establishing and producing conventional and organic hops in the Pacific Northwest” also referred to as the “WSU Cost of Production Survey” is available on the Hop Growers of America web site at: https://www.usahops.org/cabinet/data/TB38E%20Conventional%20and%20Organic%20Hops%20Enterprise%20Budget%20in%20PNW.pdf

[26] The “2020 Estimated costs of establishing and producing conventional and organic hops in the Pacific Northwest” also referred to as the “WSU Cost of Production Survey” is available on the Hop Growers of America web site at: https://www.usahops.org/cabinet/data/TB38E%20Conventional%20and%20Organic%20Hops%20Enterprise%20Budget%20in%20PNW.pdf

[27] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6187765/

[28] https://tarbell.org/2018/04/funding-bias-the-hidden-danger-lurking-in-industry-studies/

[29] I do not suggest any impropriety on the part of the researchers who compiled and analyzed the data in those reports.

[30] https://www.the-american-interest.com/2015/06/25/the-producerist-bias/

[31] https://www.agfoundation.org/common-questions/view/does-my-food-price-go-up-because-farmers-want-to-make-more-money

[32] The 2021 Hop Growers of America Statistical Packet is available at: https://www.usahops.org/enthusiasts/stats.html

[33] The 2021 Hop Growers of America Statistical Packet is available at: https://www.usahops.org/enthusiasts/stats.html

[34] Krimsky S. (2013). Do Financial Conflicts of Interests Bias Research? An Inquiry into the “Funding Effect” Hypothesis. Science Technology & Human Values. Vol. 38, No 4, pp 566-587. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/23474436.

[35] https://www.pon.harvard.edu/daily/negotiation-skills-daily/what-is-anchoring-in-negotiation/

[36] The “2020 Estimated costs of establishing and producing conventional and organic hops in the Pacific Northwest” also referred to as the “WSU Cost of Production Survey” is available on the Hop Growers of America web site at: https://www.usahops.org/cabinet/data/TB38E%20Conventional%20and%20Organic%20Hops%20Enterprise%20Budget%20in%20PNW.pdf