I summed up the current situation in a table for those who don’t want to read the entire article (Figure 1). As a continuation of the value-for-value philosophy[1], I put the summary first, so you don’t have to read to the end if you don’t want to. Reading the entire article will add clarity. Regardless, I am grateful you decided to have a look even if you don’t read the whole article. If you find any value here, please consider providing some value in return. What that means is up to you. After the previous article, I had some great conversations with people who wanted to discuss it in more detail. I received a few nice comments from people by DM. A lot of people shared the article and quite a few subscribed. Those are examples of the way people returned value for the value they received from the last article. It was great! Thank you to everybody who took the time to do that. You make writing these articles enjoyable!

Figure 1. 2023 Hop Market Forecast

THE PRESENT

In my previous article, “Hop Data Reveals Future Trends” I presented information that explained the situation up until this point. If you’ve not yet read that article, I would recommend doing that now or sometime soon.

The supply situation is clear. There is an oversupply of hops coming from the U.S. It has been growing. Why is this happening? This is something I call the Delayed Surplus Response (DSR). In August 2022, I published an article about the DSR and its effect on the cyclical nature of the hop market[2]. In a nutshell, the boom leads to the bust that nobody wants to acknowledge when it first occurs. The DSR is different from price elasticity because it happens only when demand decreases. I measured the delayed effect using the Bayesian theorem. There was consistently a delay of several years between the initial market signal and corresponding reductions in acreage. The delay is irrational. The industry was in the DSR period in 2022, and that will continue in 2023. Whether the dominance of proprietary varieties lengthens or shortens the delay remains to be seen.

Figure 2. Annual U.S. Depletion Relative to Previous U.S. Crop

Source: Data Set Calculated from USDA NASS Hop Stocks Report Source Data 2002-2022

COMMENTARY

It is important to remember in the graph above the size of the crop affects the apparent relationship with the rate of depletion. Depletion is a measure of hops shipped out of inventory (the blue line). We are comparing that to the size of the crop (the red line). Since the 2022 crop had the lowest yields since 1998 the two lines cross in 2022. If 2022 had yielded a normal crop, we would have expected the two lines to diverge still further.

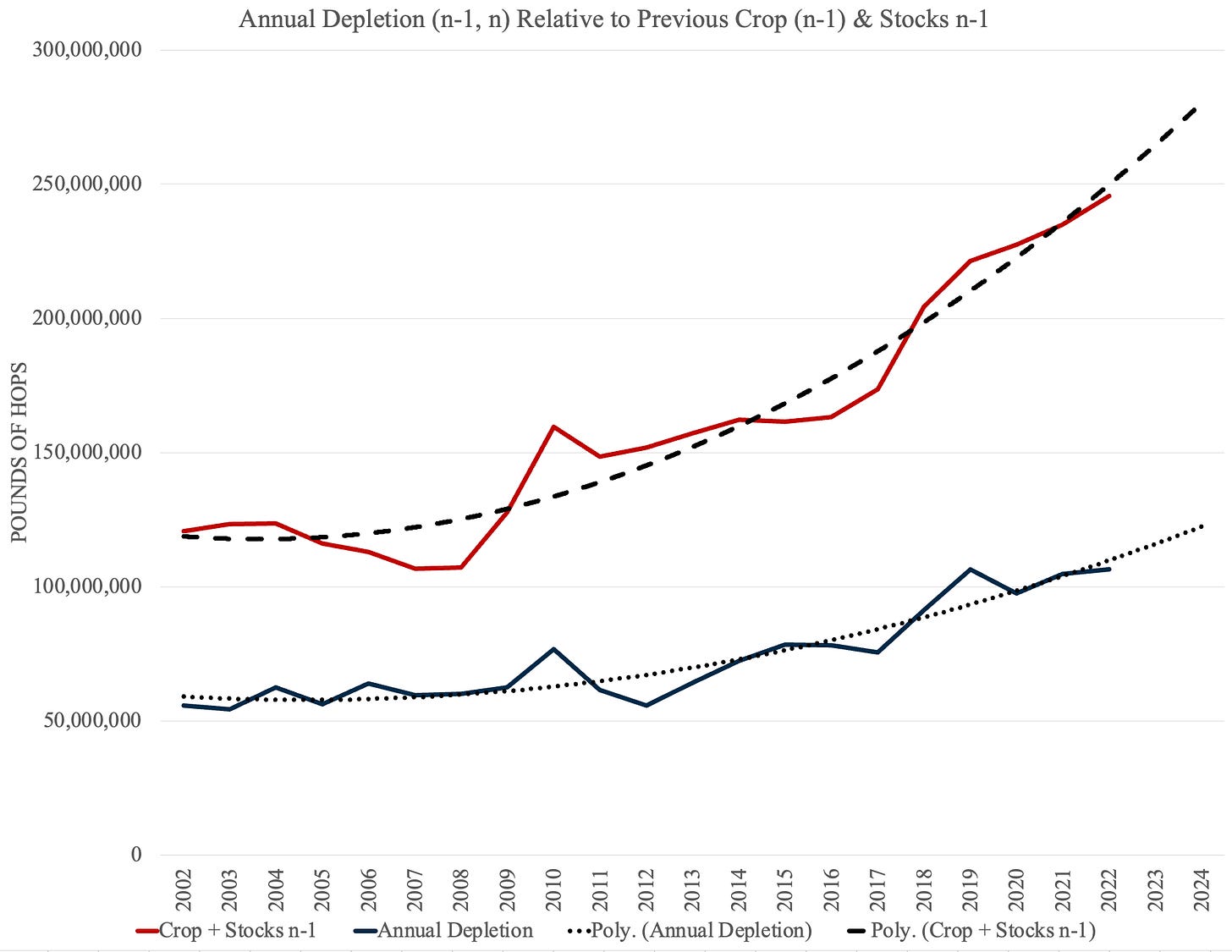

Figure 3. Annual U.S. Depletion Relative to Previous U.S. Crop from Previous Year + Available Inventories from Previous Year.

Source: Data Set Calculated from USDA NASS Hop Stocks Report Source Data 2002-2022

COMMENTARY

In this graph we can see the depletion relative to the total available supply of hops in the U.S. When compared this way, the divergence is obvious. The dotted trend lines are a projection of what could occur if no acreage reduction occurs in 2023. The dotted lines are a hypothetical projection of a production scenario I do not anticipate. This paints a clear picture as to why action must take significant action in 2023 to slow the growth of the surplus. What is important to remember is that until trellis is removed the potential production capacity remains high.

Figure 4. Difference Between Annual U.S. Depletion Relative to Total Available Supply (Crop plus Inventories) Expressed in Pounds.

Source: Data Set Calculated from USDA NASS Hop Stocks Report Source Data 2002-2022

COMMENTARY

This graph represents the growing divide between the two lines pictured in figure 3 above. This format enables the viewer to have a better concept of the rate at which inventory has been building up since 2016. During that time, the depletion gap has increased by 54 million pounds. That is a sign of a surplus.

Figure 5. Difference Between Annual U.S. Depletion Relative to Total Available Supply (Crop plus Inventories) Expressed as a Percent.

Source: Data Set Calculated from USDA NASS Hop Stocks Report Source Data 2002-2022

COMMENTARY

This graph is crucial to understanding the supply/demand relationship. It represents the growing oversupply situation in the U.S. The anomaly represents an increase in the depletion rate of 15.1 million pounds (6,879 mt.) in 2019 over 2018 levels. This may be the result of the shipment of a large volume of hops to locations not covered by the report data. There is little chance it represents a sudden increase in hop usage. There is no evidence of similar behavior in previous years and the behavior does not continue. The true reason for the anomaly remains unknown. More thorough global data is needed but none exists at this time.

Image credit: Open AI Dall-E 2: https://openai.com/dall-e-2/

THE PAST

The U.S. hop industry has been in a situation of increasing oversupply since 2016. The decreasing depletion ratios in figure 5 demonstrates its severity. According to USDA NASS data, in 2016, American farmers in the Pacific Northwest (PNW) produced 87.1 million pounds (39,508 mt.[3]) on 50,857 acres (20,589 ha[4].). In 2022, there were 59,785 acres (24,204 ha.) in production in the PNW that produced 101.2 million pounds (45,904 mt.) despite a yield of 1,694 pounds per acre (1.89 mt./ha.), the lowest yield on record since 1998 (before high-yielding super alpha hops became popular). The poor harvests in the U.S. and EU created were a blessing in disguise. They created an opportunity to sell tens of millions of pounds of inventory that would have languished in storage. It also created some relief for brewers with unwanted contracted volumes to escape some of their deliveries for a year. The lack of a corresponding price signal demonstrates the severity of the surplus.

It would be simple to subtract 50,857 from 59,785 and conclude the U.S. industry should remove 8,928 acres (3,614 ha.) to be in balance. This is a familiar predicament that has plagued the hop industry for decades. This is the first time in history when the oversupply was caused by proprietary aroma hop varieties.

“History Does Not Repeat Itself, but it Rhymes”

- Unknown (often attributed to Mark Twain[5])

As it has in the past, a surplus combined with contract levels that do not represent demand created disequilibrium and kept appropriate price signals from reaching the market leading to a correction.

Craft beer production has increased. Craft brewers use more hops than the macros. Therefore, there must be a greater demand for hops (or so the logic goes). Confirmation bias causes people to value the information that supports their beliefs. Not even Covid and reduced beer production interrupted U.S. acreage increases. Those hops were contracted after all.

Here are some facts. The difference between 2016 and 2021 craft beer production is 187,396 barrels[6][7][8]. If that production was all hoppy IPAs made with six pounds of hops per barrel, it would create a demand for 1.1 million pounds of hops over 2016 levels. That would require an additional 599 acres (242 ha.) of U.S. hops based on the average hop yield between 2016 and 2021 of 1,877 pounds per acre (2.1 mt./ha.)[9]. That leaves 8,328 acres (3,371 ha.) whose continued existence must be determined for 2023 and beyond. Using the 2016-2021 average yield, that acreage can produce 15.6 million pounds. But wait, … the situation is more complicated. The USDA Hop Stocks Report includes imported hops and does not account for exported hops. According to the 2022 HGA Statistical Packet, in 2022, there was a 35.5-million-pound trade surplus (meaning the U.S. exported 35.5 million pounds more than it imported)[10]. I will describe how the situation ahead for American farmers is more challenging … but first a few graphs.

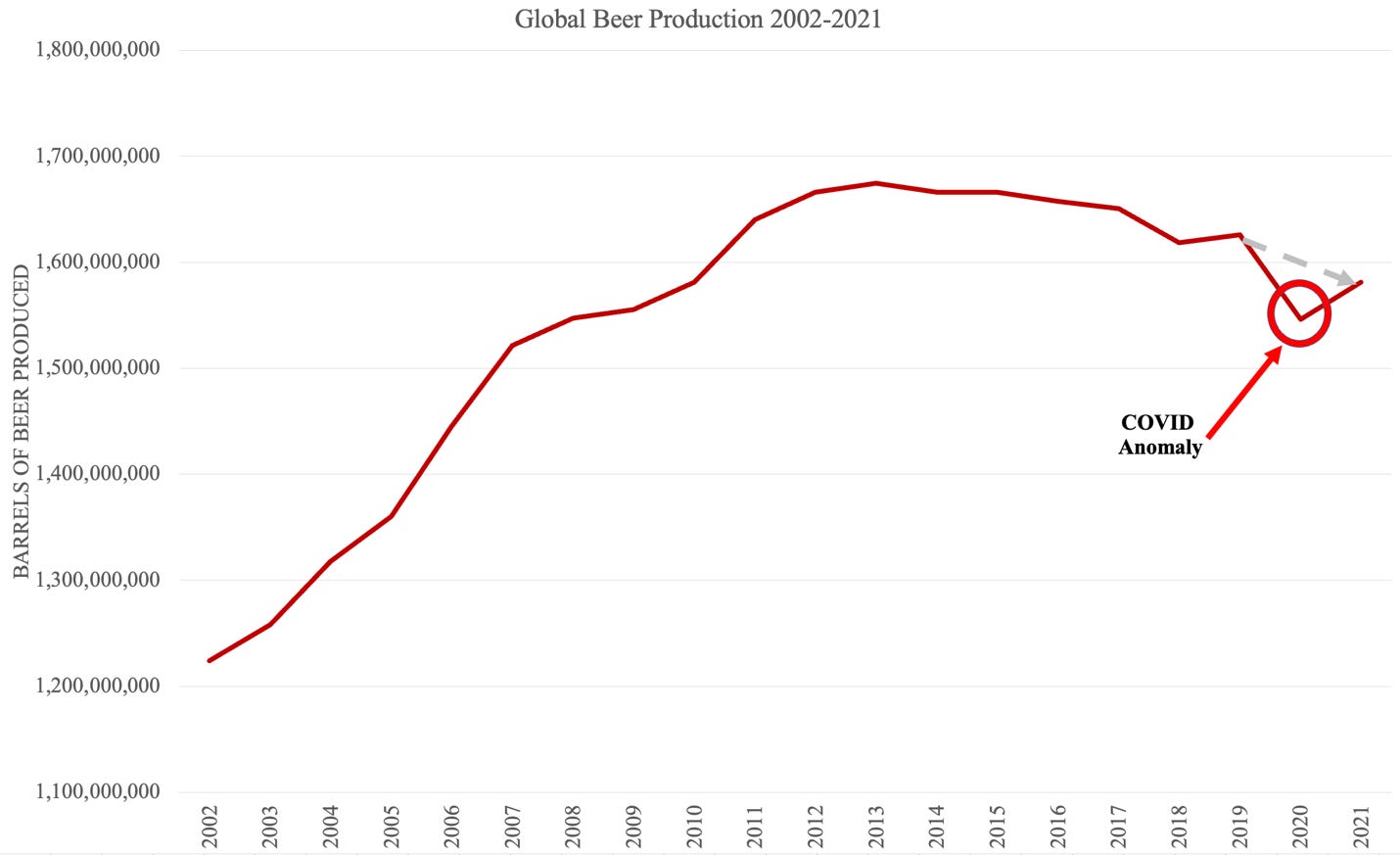

Figure 6. Global Beer Production 2002 - 2021.

Source: Data Set Calculated from Statista.com Data[11]

Figure 7. US Beer Production 2002 - 2021.

Source: U.S. Department of the Treasury Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB)[12].

Figure 8. Craft Beer Production 2005 - 2021.

Source: Brewers Association National Statistics[13].

COMMENTARY

Craft beer has supported the rapid growth of proprietary varieties. It appears to have entered a mature stage of its life cycle. Craft, U.S. and global beer production are all on the decline. Should consumer preferences move away from hop forward IPAs, growth in the craft beer market could translate into reduced hop demand.

The challenge ahead for the hop industry is severe. To say an acreage reduction of 8,328 acres (3,371 ha.) today would bring supply in line with demand though is an oversimplification. The idea of removing 8,328 acres (3,371 ha.) may not be extreme enough because it does not account for surplus remaining in the United States and elsewhere. The quantity of hops that were contracted but are now unwanted is in the millions of pounds per year. On the Lupulin Exchange alone at the time of this publishing, there were 1.1 million pounds of hops available[14]. Some date back to 2016! Merchants are monitoring that platform. Brewers who do not wish to signal they are over bought should post with caution. Reports of brewery excess inventory not available on the Lupulin Exchange are significant. If they want to sell their inventory in this atmosphere, they will need to offer more aggressive pricing.

The idea of removing 8,328 acres (3,371 ha.) may be too extreme because it does not account for the American hops stored overseas. Those quantities are not public information. Global inventory buildup is where the picture becomes blurry. This is where the facts end, and speculation begins. That is why it is not possible with the available data to say an exact number of acres that must be removed to reach equilibrium. If the trend in the U.S. with regards to inventory buildup of American proprietary varieties indicates behavior in other parts of the world, the situation is serious. There is no reason to believe inventories of American hops outside the U.S. are moving out of inventory at a different rate than they are within the borders of the United States. The same companies manage them. The economies of other countries are no healthier than that of the U.S.[15]

The DSR implies that decreasing production always trails behind changes in demand leading to a buildup of hop inventory. Current data demonstrate this has been underway for several years. The current overproduction could be due to IP owners losing track of, ignoring or never understanding true demand signals. The cause is not important now. The farmers and merchants who own the IP are in a battle for market share with each other. To them, it is a zero-sum game. Nobody wants to give any ground to their competitor.

Two such examples happened at the beginning of Covid. Yakima Chief Hops asked its farmers to decrease production by seven percent in 2020 in response to Covid. The Oregon hop commission requested its farmers reduce production by 7-10 percent[16]. Despite these reasonable requests American hop farmers harvested a record acreage in 2020[17]. It seems those requests were ignored. Requests are just that … request. The articles reporting on those requests made them sound like they anticipated the problem and took proactive steps to correct it. They did not. Merchants and farmers play semantic games with the media all the time. When you know the truth, the half-truths stand out and lies are painful to watch. I played that game too when I was a dealer. No more! In a future article, I will decipher some hop propaganda to help people who buy hops understand the rules of the game.

“Then ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free.”

- John 8:32, KJV

A Sea Change

Increased prices due to inflation combined with production challenges has led to lower beer sales[18][19][20]. Those continuing to drink beer in the U.S. are moving away from hop forward IPAs and diversifying their drinking preferences[21][22]. Lagers, which use fewer hops than IPAs, have been forecast to outsell IPAs for some time and are now increasing in popularity[23][24][25][26][27]. Healthier lifestyles and reduced alcohol consumption are gaining popularity[28]. Prominent celebrities admit they have quit alcohol[29]. Dry January is popular[30]. Sober October is popular[31]. Gen Zers are sober curious all the time[32]. A 2019 Google poll found that 40% of Gen Zers associated alcohol with vulnerability, anxiety and abuse[33]. It appears a sea change is under way.

According to Bart Watson, Chief Economist of the Brewers Association, craft beer is losing its appeal to younger drinkers[34]. It’s losing more than that. Beer has lost sales to ready to drink (RTD) cocktails across several age groups[35]. When Gen Zers drink, they often drink RTD spirits[36]. The RTD category soared during Covid and is set to displace wine as the most popular alcohol category[37]. The RTD trend is forecast to continue to increase through the decade[38][39][40]. That will affect craft beer demand. Part of the reason for that decline is increasing competition, rising costs, the economy and shifting consumer habits following the COVID-19 pandemic[41]. The decrease in craft beer purchases between 2021 and 2022 according to the National Beer Wholesalers Association (NBWA) Beer Purchasers’ Index is significant (Figure 9)[42].

Figure 9. Decrease in Craft Beer Purchases Between 2021 and 2022

***

Past is Prologue

According to the International Hop Growers Convention (IHGC) the global hop industry produced 53 MILLION POUNDS (24,084 MT.) FEWER hops in 2022 than in 2021, an 18.5% decline on only 207.5 fewer acres. In 2022, German farmers harvested 28% fewer hops than in 2021. Czech farmers produced 48% fewer hops in 2022. American production was down 11.9%[43]. There was NO price reaction! That fact alone demonstrates the severity of the global hop surplus.

A similar thing happened in 2003 when German farmers produced 21.4% fewer hops than in 2002 with no reaction from the market. The 2003 event tightened inventory, which led to the price spike that occurred in 2007-08. U.S. season average price increases reveal merchants were aware of the tight supply situation as early as 2004 and conservatively increased prices through 2006 so as not to encourage speculative planting. The industry was unregulated in 2004-06. Spot market purchases and a decades long surplus separated demand signals from market activity. By contrast, the U.S. industry in 2023 is regulated by proprietary variety licensing agreements and the IP rights associated with them. According to the 2022 USDA National Hop Report, the Hop Breeding Company (HBC) owned proprietary varieties produced on 51% of U.S. acreage. Five other companies owned the varieties produced on an additional 18% of U.S. acreage[44].

The Shortage that Never Was

Contrary to popular belief, there was never a shortage. Global beer production during that period increased (Figure 6). I remember in January 2008, one farmer turned down my offer to buy 40,000 pounds (18.14 mt.) of Willamettes for $20/pound (33 Euros/Kg. in 2008 USD[45]). He wanted $22/pound because he claimed because his “… neighbor received that for his hops”. By February of that year, brewers had tired of hop industry greed. They felt comfortable they could survive until the 2008 crop. In response to high prices, 2008 hop PNW acreage increased by 9,987 acres (4,043 ha.), a 32% increase over 2007. It was an example of how American hop farmers can increase acreage in response to demand when they are free from regulation. The market for hops at any price shut down. By 2009, a massive surplus had developed. Brewers abandoned or renegotiated their contracts en masse. Thousands of acres of trellis that had been planted for alpha hop acreage became available for aroma hops. In one of life’s ironies, what many thought was a catastrophe paved the way for the craft beer success story. It was a positive. Nevertheless, hop farmers changed the way they calculated and reported their cost of production to brewers in 2010. They used Washington State University to wash the data in what appears to be an act of revenge for the previous years’ contract cancellations. Those changes continue to influence hop prices for brewers large and small to this day[46][47].

“Certainly, then, envy is the worst sin there is. For truly, all other sins are sometimes against only one special virtue; but truly, envy is against all virtues and against all goodnesses.”

- Geoffrey Chaucer – The Parson’s Tale[48]

Following the meteoric rise of craft breweries and the aroma hops they purchased following 2010, the U.S. reached peak proprietary in 2020. Back then, 70.19% of U.S. acreage and 73.44% of U.S. production had some form of IP[49]. Along with all that proprietary acreage came record high prices (Figure 10). Since 2020, the proprietary hold over the industry softened to 68.11% and 71.82% for acreage and production respectively. The trend toward patenting and trademarking is not unique to hops. Bayer (formerly Monsanto) uses the fear of lawsuits to dominate the corn and soybean markets where they control 86% and 93% of the markets respectively[50]. The ability to sue one’s competitor is the allure of patents as explained by Elon Musk in this short video.

Reversion to the Mean

According to Investopedia, “Reversion to the Mean” is defined as:

“Mean reversion, or reversion to the mean, is a theory used in finance that suggests that asset price volatility and historical returns eventually will revert to the long-run mean or average level of the entire dataset.”[51]

This is true of political power, finance and hop prices. When I present season average prices over a long term, I add the lines demarking standard deviations and the long-term average so it’s obvious how far away from “average” prices have moved (Figure 10). That’s important! The further away they move, the more pressure they must return to normalcy. The effects of the boom-and-bust cycle can be seen when prices from the previous 75 years are viewed. The video below presents the reasons for boom-and-bust cycles in an entertaining way. How far prices fall and when will depend on farmer actions in 2023 and 2024.

“Prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future.”

- Danish Proverb[52]

Figure 10: U.S. Season Average Prices Adjusted for Inflation Using the Consumer Price Index to 2022 USD with Standard Deviation Demarcation and Mean. 1948-2022.

Source: USDA NASS, Bureau of Labor Statistics

Figure 11. U.S. Season Average Prices Raw Data and Prices Adjusted for Inflation Using the Consumer Price Index to 2022 USD 1948-2022.

Source: USDA NASS, U.S. Inflation Calculator[53]

In short, pressure from extreme prices (low or high) leads to a reversion to the mean. Season average hop prices, when adjusted for inflation, have been significantly higher than their 75-year average since 2015 (Figure 10). That is a long time for such an extreme high to remain in place. As figures 10 and 11 demonstrate, it is more common for prolonged periods of price activity to exist below the long-term average than above. Farmers have long wanted to correct this trend. The intellectual property rights associated with proprietary varieties gave them the chance. This prolonged stay at almost two standard deviations above the norm led to irrational behavior was unusual and an anomaly. The younger generation running today’s hop farms has not known the types of challenges that are on the horizon. Their parents do.

I think boom-and-bust cycles are fascinating. The founder of Bridgewater Associates, Ray Dalio, published his book “Principles for Dealing with The Changing World Order”, in 2021. In it, he discusses market cycles. He explains the different life cycles of a country, which can be applied to the hop industry example. If you haven’t read that book or his new book, “Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises”, this video he made about a year ago explains the first book in a nutshell. If you can find the time, it’s worth your time in my opinion. There are MANY parallels between the principles explained in Ray’s video and the hop industry.

The hop industry has survived boom-and-bust cycles for centuries. The current situation will lead to industry changes and further consolidation that will be painful for some, but not others. I will explain who the winners and losers will be in an upcoming article.

The Cause of the Imbalance

Most people like to assign blame. Let’s explore how that argument goes with regards to the current hop surplus. Prior to the existence of proprietary varieties, this would have been a ridiculous exercise. In the days of public varieties, it was every farmer’s opportunism mixed with greed, secrecy and lack of communication that led the industry to over plant and create surpluses … as they did in 2008. Three Federal marketing orders in the 20th century attempted to get the situation under control. They all failed.

For much of the past 10 years, the control of the industry has been in the hands of those who own proprietary varieties. They influenced decisions regarding planting, pricing, sales and distribution. Their influence and power grew along with the acreage of the varieties they owned. So, they’re at fault, right? Not so fast.

“With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility”

- Popularized by the Spiderman Comics and Marvel Movies

American farmers committed significant resources to proprietary varieties over the past decade. They relinquished their autonomy to the IP holders in the process. Despite having full spectrum dominance over proprietary varieties, it appears the supply of those varieties got out of control. Patent law much like Federal marketing orders cannot overpower human nature. So, are they to blame for the current situation?

The hype around craft beer around 2015 was palpable. It was fed by craft brewery demand. The Brewers Association added fuel to the fire when they supported the idea that 20 percent of U.S. beer would be craft by 2020. That crazy idea sounded reasonable to me and most everybody else in the hop industry at the time. It created a frenzy atmosphere. If true, it meant another doubling of acreage! Farmers constructed hop trellis in areas not known for hop production in addition to those that were in anticipation of the good times to come[54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61]. Land was the scarcest resource. Good times did come. Prices were higher than at any time since 1952 (Figure 10). I remember selling hops back then in my previous life. Farmers kept saying they needed higher prices. We would pass that message along to the brewers. Brewers kept signing contracts for more and more hops regardless of price. It was the beginning of the bubble that exists today.

So … What happens next? A lot of finger pointing and very little acceptance of responsibility. Hop merchants will blame brewers for signing contracts for proprietary varieties that from their perspective were not necessary. Brewers will blame farmers and merchants for forcing them to sign long-term contracts when they could not predict demand. The line between farmer and merchant is much more blurred than ever before. Farmers will say they were producing for their contracts. They all share the blame. In my opinion, the problem lies with inflexibility of the contract system that locks in customers for the long term, but that’s a topic for another article.

THE FUTURE

Everything mentioned in this article so far led to the current surplus inventory. The capacity to produce the 53 million pounds that did not materialize in 2022 still exists. Different news sources seem to be mixed on whether there will be a recession in 2023. If a recession occurs, it will be an inflationary recession (i.e., stagflation[62]). Stagflation creates circumstances that are difficult to correct[63]. Based on job market data, US Bank and JP Morgan say no recession is coming, and things may be improving[64][65]. The FED, the World Bank, the World Economic Forum, the International Monetary Fund and the Bank of England, however, say a recession is likely in 2023[66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73]. The Economist magazine is one of the few sources to make the case that a recession is inevitable[74]. It seems the majority believe a recession is likely. The St. Louis FED compared the current situation to previous recessions by measuring the number of U.S. states with negative economic growth (Figure 12)[75]. As you can see, the outlook is not good.

Figure 12: Number of U.S. States with Negative Economic Growth 1979-2022.

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank

Beer has long been thought to be recession proof. Bart Watson, chief economist at the Brewers Association in 2020 said that craft beer, imports and premium beer did not suffer during the previous recession because the recession “did not inflict as much pain on the class of people who tend to drink Session IPAs, artisanal Porters, Belgian Lambics and Saison pale ales. Likewise, in this pandemic and recession, craft beer drinkers are more likely to have the luxury of working remotely, keeping their jobs and spending a few extra bucks on beverages with flavor”[76]. I agree with Bart. During the previous recession, however, inflation was near zero and Quantitative Easing (QE) pumped trillions of dollars into the economy[77].

Things are different in 2023. Inflation is a tax on people living on a budget[78]. The average level of inflation during 2022 was 8.0%[79]. If there is another recession, how will stagflation affect the craft beer industry? The last time the U.S. had stagflation was 1973-1983[80]. Craft was in its infancy. Regardless, RTDs will continue to pose a challenge to craft during the coming years. Supply shortages of everything from CO2[81] to aluminum[82] and glass[83] create a challenging future for the craft beer segment increasing the cost of production when people can’t afford higher prices[84]. One of the few things not at risk of being in short supply are hops.

There may be some hope on the horizon. Craft beer sales have increased in recent years, although they have not returned to pre-covid levels[85]. The Lipstick Index, coined by Estée Lauder's Leonard Lauder, is the theory that sales of affordable luxuries rise during economic downturns. It’s based on increasing sales of lipsticks during the 2001 recession. The index already shows promising signs for 2023[86][87]. Craft beer is considered by some to be an affordable luxury[88]. Craft beer, like a Starbucks coffee, might be something people won’t give up even during the most difficult times due to the value the experience[89]. It remains to be seen how craft beer will respond to stagflation. If Starbucks’ 2022 performance is any indication how affordable luxury brands might fare in 2023, the craft beer segment might be ok[90].

If you made it this far … even if you just scrolled to the end, I would like to thank you for visiting. Knowing that some people enjoy these articles makes them even more enjoyable for me to write. I have plenty of articles I plan to write about still. If you have a topic you would like me to explore, please let me know. You can message me on LinkedIn.

[1]https://value4value.info

[2] MacKinnon D, Pavlovič M. The delayed surplus response for hops related to market dynamics. Agric. Econ. - Czech. 2022;68(8):293-298. doi: 10.17221/156/2022-AGRICECON.

[3] “mt” is an abbreviation for metric ton. One metric ton equals 2,204.6 pounds

[4] “ha” is an abbreviation for hectares. One hectare equals 2.47 acres.

[5] https://quoteinvestigator.com/2014/01/12/history-rhymes/

[6] The most current numbers available at the time of this writing

[7] https://www.ttb.gov/beer/statistics

[8] https://www.brewersassociation.org/statistics-and-data/national-beer-stats/

[9] https://www.usahops.org/enthusiasts/stats.html

[10] https://www.usahops.org/img/blog_pdf/435.pdf

[11] https://www.statista.com/statistics/270275/worldwide-beer-production/

[12] https://www.ttb.gov/beer/statistics

[13] https://www.brewersassociation.org/statistics-and-data/national-beer-stats/

[14]https://lupulinexchange.com

[15] https://www.forbes.com/sites/simonconstable/2022/04/26/europe-faces-higher-recession-risks--than-usa/?sh=7bf2e5b064f0

[16] https://www.goodbeerhunting.com/sightlines/2020/5/13/covid-19-forces-us-hop-farms-to-cut-production-during-historic-growing-season

[17] https://www.yakimaherald.com/news/local/hop-growers-make-changes-adjust-acreage-in-response-to-covid-19-pandemic/article_64c56709-9fca-513f-8b59-73095458b508.html

[18] https://www.today.com/video/beer-prices-skyrocket-leaving-sales-going-flat-159697477891

[19] https://www.wsj.com/articles/beer-sales-drop-as-consumers-balk-at-higher-prices-11673010058

[20] https://winenews.it/en/key-trends-in-world-alcohol-consumption-in-2023-by-iwsr-how-much-will-the-economic-crisis-weigh-on_486404/

[21] https://www.axios.com/local/denver/2023/01/05/colorado-breweries-trends-2023

[22] https://learn.uvm.edu/blog/blog-business/4-craft-beer-industry-trends-to-watch-in-2023

[23] https://buffalonews.com/entertainment/buffalo-beer-experts-predict-craft-beer-trends-in-2023/article_c6b50c42-9042-11ed-8af1-4b9b0fc41723.html

[24] https://dcbeer.com/2022/12/22/2022-beer-in-review/

[25] https://www.linkedin.com/news/story/have-we-reached-peak-craft-beer-5515308/

[26] https://draftmag.com/ipa-vs-lager/

[27] https://www.allagash.com/blog/what-is-a-session-beer/

[28] https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/jan/15/last-orders-how-we-fell-out-of-love-with-alcohol

[29] https://www.cosmopolitan.com/uk/body/health/a33323277/sober-celebrities/

[30] https://www.today.com/health/dry-january-what-it-what-are-benefits-women-t146331

[31] https://www.healthline.com/health-news/sober-october-what-a-month-of-no-drinking-can-do-for-your-health

[32] https://www.delish.com/food/a38772407/sober-curious/

[33] https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20220920-why-gen-zers-are-growing-up-sober-curious

[34] https://www.bizjournals.com/denver/news/2021/09/25/craft-brewers-confercence-younger-drinkers-watson.html

[35] https://www.cnbc.com/2022/10/27/beer-is-on-pace-to-lose-its-leading-share-of-the-us-alcohol-market.html

[36] https://www.forbes.com/sites/joemicallef/2022/09/14/why-demand-for-rtd-beverages-is-skyrocketing-the-distilled-spirits-council-report/

[37] https://www.thespiritsbusiness.com/2021/06/rtds-to-become-second-biggest-alcohol-category-in-us/

[38] https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/the-ready-to-drinks-rtds-alcohol-market-is-projected-to-grow-at-a-cagr-of-11-2-during-the-period-2022-2030--claims-insightace-analytic-301627968.html

[39] https://www.foodnavigator.com/Article/2023/01/04/low-no-alcohol-consumption-to-rise-a-third-by-2026#

[40] https://www.forbes.com/sites/katedingwall/2022/10/07/spirit-based-ready-to-drink-products-will-pull-116-billion-in-growth-over-the-next-five-years/?sh=5138a0696a5d

[41] https://www.chicagotribune.com/dining/drink/ct-food-drink-brewery-closings-chicago-20221208-gwc2exk7gjg4tcstijlcbbgnoq-story.html

[42] The NBWA Beer Purchasers’ Index (BPI) is an informal monthly statistical release giving distributors a timely and reliable indicator of industry beer purchasing activity. BPI is the only forward-looking indicator for the industry to measure expected beer demand (one month forward) in the marketplace. Similar to the widely recognized Purchasing Managers’ Index, the BPI is a net-rising index and a leading indicator of industry performance based on survey responses from participating beer purchasers. The index surveys beer distributors’ purchases across different segments and compares them to that of previous years’ purchases. A reading greater than 50 indicates the segment is expanding, while a reading below 50 indicates the segment is contracting. The above text may be found at: https://nbwa.org/resources/beer-purchasers-index/

[43] http://www.hmelj-giz.si/ihgc/doc/2022_NOV_IHGC_EconComm_SummaryReport.pdf

[44]https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Regional_Office/Northwest/includes/Publications/Hops/2022/hopsan22.pdf

[45] at the exchange rate of 1.467 Euros/USD according to Macrotrends available at: https://www.macrotrends.net/2548/euro-dollar-exchange-rate-historical-chart

[46] https://rex.libraries.wsu.edu/esploro/outputs/report/2004-estimated-cost-of-producing-hops/99900501513501842

[47] http://ses.wsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/FS028E.pdf

[48] https://chaucer.fas.harvard.edu/pages/parsons-prologue-and-tale

[49]https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Regional_Office/Northwest/includes/Publications/Hops/2022/hopsan22.pdf

[50] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/feb/12/monsanto-sues-farmers-seed-patents

[51] https://www.investopedia.com/terms/m/meanreversion.asp

[52] https://quoteinvestigator.com/2013/10/20/no-predict/

https://www.usinflationcalculator.com

[54] https://www.cnbc.com/2016/03/04/an-ancient-craft-is-brewing-up-new-jobs.html

[55] https://www.entrepreneur.com/starting-a-business/craft-brewers-this-is-what-your-customers-want/246092

[56] https://www.brewersassociation.org/press-releases/craft-brewer-volume-share-of-u-s-beer-market-reaches-double-digits-in-2014/

[57] https://www.forbes.com/sites/niallmccarthy/2015/06/17/2014-was-another-great-year-for-american-craft-beer-infographic/

[58] https://brewpublic.com/beer-news/craft-brewer-volume-share-of-u-s-beer-market-reaches-double-digits-in-2014/

[59] https://www.realbeer.com/craft-beer-surpasses-10-market-share/

[60] https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2014/05/09/310803011/as-craft-beer-starts-gushing-its-essence-gets-watered-down

[61] https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/enterprise_budgets_for_hops_now_available

[62] https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/stagflation.asp

[63] https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/06/07/stagflation-risk-rises-amid-sharp-slowdown-in-growth-energy-markets

[64] https://www.jpmorgan.com/insights/research/market-outlook

[65] https://www.today.com/video/beer-prices-skyrocket-leaving-sales-going-flat-159697477891

[66] https://www.reuters.com/markets/us/new-fed-research-flags-rising-risk-us-recession-2022-12-30/

[67] https://www.weforum.org/press/2023/01/chief-economists-say-global-recession-likely-in-2023-but-cost-of-living-crisis-close-to-peaking/

[68] https://www.reuters.com/markets/world-bank-warns-global-economy-could-easily-tip-into-recession-2023-2023-01-10/

[69] https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/09/15/risk-of-global-recession-in-2023-rises-amid-simultaneous-rate-hikes

[70] https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2022/dec/are-state-economic-conditions-harbinger-national-recession

[71] https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/jan/02/third-of-world-economy-to-hit-recession-in-2023-imf-head-warns

[72] https://www.bbc.com/news/business-64142662

[73] https://think.ing.com/articles/warnings-over-britains-long-and-deep-recession-are-exaggerated1

[74] https://www.economist.com/the-world-ahead/2022/11/18/why-a-global-recession-is-inevitable-in-2023

[75] https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2022/dec/are-state-economic-conditions-harbinger-national-recession

[76] https://www.npr.org/sections/money/2020/07/07/887660648/what-beer-sales-tell-us-about-the-recession

[77] https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2022-09/57519-balance-sheet.pdf

[78] https://blogs.worldbank.org/africacan/taxing-the-poor-through-inflation?sfw=pass1674485577

[79] https://www.usinflationcalculator.com/inflation/historical-inflation-rates/

[80] https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2022/07/01/todays-global-economy-is-eerily-similar-to-the-1970s-but-governments-can-still-escape-a-stagflation-episode/

[81] https://www.craftbrewingbusiness.com/featured/the-co2-shortage-part-1-why-is-there-a-co2-shortage-for-beer-makers/

[82] https://www.cbsnews.com/miami/news/brewers-across-the-country-are-dealing-with-an-aluminum-can-shortage/

[83] https://www.dallasobserver.com/restaurants/dont-panic-but-the-topo-chico-shortage-is-getting-real-12579264

[84] https://www.just-drinks.com/comment/2023-outlook-pockets-of-positivity-in-an-otherwise-pessimistic-beer-industry-landscape/

[85] https://www.brewersassociation.org/statistics-and-data/national-beer-stats/

[86] https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-63047913

[87] https://moneywise.com/investing/stocks/when-the-lipstick-index-flashes-green

[88] https://www.cnbc.com/2014/05/03/the-bmw-of-beer-brewery-crafts-luxury-approach.html

[89] https://www.thestreet.com/investing/stocks/can-starbucks-sbux-stock-shake-off-a-recession

[90] https://uk.finance.yahoo.com/finance/news/starbucks-q-4-earnings-preview-heres-what-to-expect-135933632.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAH9qp1HvM0OMoZU_KWlCt0UPvNvgQoW5Qn3dQyc0w6qtzkem9fR-qpaq47l9Om4J-ujMGEXGt_Q_6BKXiaIG0cvzz2k6D9sbBq_K4DMFZW8Ue4omGc1X7TxcCd0PG_kp35xiZ3zk2Cv30A1ZdWwS1QK2gB-7VG_GG-3O22G1boxS