OCTOBER SURPRISE

When I wrote my August 3, 2023 article, “Hop Price Manipulation 101”, the official outlook from hop merchants and farmers was not good. I mentioned the joke about American hop farmers and how they lose their crop 10 times before they deliver an average crop. It seems the crop in the U.S. and Europe improved since those forecasts of doom and gloom. This year’s crop will be … about average[1]. The hop industry highlights each little challenge because fear is good for business. Over the next month, I anticipate this year’s production estimates will continue to improve. By the time everybody meets at Brau, the focus will be on the 2024 crop and how it might be short due to: another round of acreage reductions[2] and climate change[3][4][5][6][7]. Contracting, of course, will be the solution for breweries to secure their supply … except it isn’t. I’ll touch on that in a couple paragraphs.

“Prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future.”

- Niels Bohr (winner of the 1922 Nobel Prize in physics)

SEPTEMBER 1 HOP STOCKS REPORT

If you don’t already know, the USDA released the most recent September 1 Hop Stocks survey results on September 18th. This report contains some of the most important data released each year. If you’re interested, you can download it for yourself here. While you’re there, you can subscribe to receive USDA reports the day they are released. The latest stock report reveals a continued imbalance in levels of hop stocks. That’s no surprise. The U.S. would have needed to cut its production by 50% to fix the problem in one year. In addition, it reveals several other trends that are not obvious at first glance.

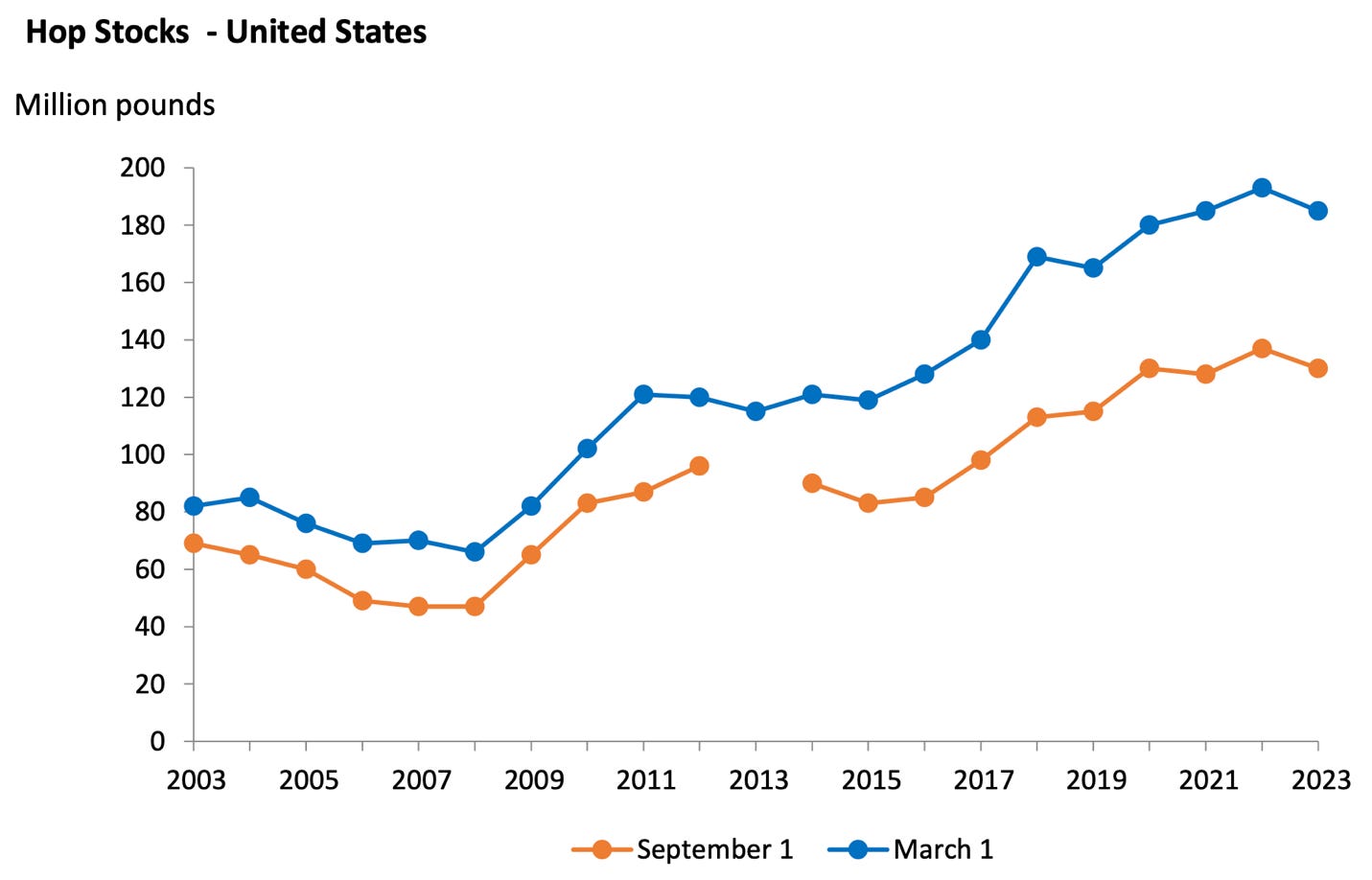

I suspect the way the USDA presents the information discourages people from digging into the details of the report (Figure 1). It’s hard to get much out of the graph they use. It appears hop inventory in storage is decreasing. Is it though?

Figure 1. USDA March 1 and September 1 Hop Stocks graph

Source: USDA

Earlier this year, during the Hop Growers of America convention, Alex Barth acknowledged the existence of a 40-million-pound (18,143 MT) surplus of hops. At the time, he suggested the industry would need to cut 10,000 acres (4,048 hectares) to bring supply back in line with demand[8]. That was a noble goal even if he underestimated the size of the surplus.

WHAT CAUSED THE SURPLUS?

It is clear the inventory buildup began long before Covid (Figure 2).

Figure 2. USDA September 1 Hop Stocks 1947-2023

Source: USDA September 1 Hop Stocks data 1947-2023

I demonstrated in previous articles how the surplus started accumulating Covid. Still this summer, some farmers are trying to deflect responsibility for the surplus onto Covid[9]. In 2018, at the Hop Growers of America convention, Louis Gimbel, CEO of HopSteiner, told convention attendees the market was already oversupplied[10]. At least one merchant claimed they reduced production in 2020 in anticipation of what Covid would do to the brewing industry[11][12]. It took a while, but it became obvious they didn’t, and that weather was responsible for reduced production in 2020[13][14]. According to the Hop Growers of America, farmers in the Pacific Northwest planted an additional 2,097 acres (848 hectares) in 2020[15]. According to data reported by Hop Growers of America to the International Hop Growers Convention, 98% of the 2020 crop was sold[16]. This type of deception and misdirection is often used by merchants/farmers to distract brewers not familiar with how the system works. In this case, It was used to deflect attention away from the real cause of the surplus.

The perspective in Figure 2 hints at surpluses and deficits in the system and how they have changed over time (more on that below). Since 2012, the hop industry’s inventory liability soared higher each year. This coincided with the entry of thousands of small new craft breweries, a 399% increase in proprietary variety production and irrational exuberance in the market. Before we continue to analyze the hop inventory and the information revealed in this most recent report, a brief discussion about contracting is necessary so we are all on the same page.

THE CONTRACT SYSTEM

Merchants love the current contracting system[17]. It’s good for business. It should be. They created it. Contracts are the equivalent of brewery subscriptions for a hop merchant. According to this 2020 Forbes article, the subscription customer business model is profitable. They can help B2B companies “build long-term, profitable and sticky relationships with clients”[18]. When contracts work, they remove the need for merchants to compete for business each year based on their merits. Contracts reduce the staff necessary for new customer acquisition. Contracts create predictable recurring revenues. I can attest to that. When I was a hop merchant, with two salespeople I was able to sell millions of pounds of hops to over 400 customers in 40 countries. Bankers that finance the hop industry want contracts to continue. It makes their job easier.

TANGENT ABOUT CONTRACT VALUE

Let’s consider the impact of a hop contract on the industry to demonstrate why they are so attractive. Spoiler alert: it’s not about a brewer’s need for hops.

For this example, let’s pretend it’s 2015. The Brewers Association was promoting its goal of “20 by 20”. They promoted the idea that craft breweries would enjoy 20% of the U.S. beer market by 2020[19]. They when it became clear that would never happen, the Brewers Association redefined their claim as “aspirational”[20]. Nevertheless, at the time, it added to the hype and irrationality in the market. (Fun Fact: In 2022, craft beer had 13.2% of the U.S. market[21]) All that excitement meant that five-year hop contracts at constant or increasing volumes were the norm.

In this example, the farmer has a contract for raw hops with the merchant for 100,000 pounds (45 MT) of hops for $600,000. That merchant has a corresponding contract with the brewery for pellets for $900,000. Every company in the American hop industry uses a line of credit. The bank has a formula for establishing that line of credit that considers a contract’s face value as part of the equation[22]. The value of the inventory on hand and other company assets may also be considered as collateral.

When our banker meets with the merchant and the farmer to discuss the lines of credit, he sees profitable contracts with American customers. He is comfortable lending money using these contracts as collateral. To keep this example very simple, let’s assume he uses only the face value of the forward contract in the current year to establish the credit limit for this year. The farmer’s books show that his expenses are high. He claims the hops will cost him $540,000 to produce. There’s $60,000 profit on his deal. The merchant has a different situation. In addition to the cost of the raw hops, he has processing, storage and other fixed expenses he must incur for total expenses of $750,000. Still, he estimates he will make $150,000 on the deal.

To our banker, these profitable contracts look like great collateral. He lends the merchant $750,000 and the farmer $540,000 for a total of $1.29 million. The brewery and the merchant pay nothing to sign these contracts. That money is created out of thin air[23]. On paper, there is no problem with these deals. That is the world in which the banker lives. The contracts justify his lending decisions for each entity while ignoring their cumulative effects. In fact, he could lend more.

END OF TANGENT

When hop contracts work as designed (by the hop industry), they flood the industry with money. They lock their customers into paying for purchases whether they need them or not. The higher the prices, the more money floods the industry regardless of the actual cost of production. Inflating the reported cost of production, as the U.S. hop industry has done since 2010 (see “How Much Do Hops Really Cost?”) further inflates prices … and the amount of money flooding the system. The system breaks down when a customer can’t or won’t pay for its contracted hops within the 12 months after harvest. It is a house of cards. The presence of thousands of small craft breweries and their inability to predict the future destabilizes the situation still further because the contracts they signed were not designed for them.

The result is that merchants holding inventory in 2023 are in a precarious position for the following reasons:

· Stagnant inventory since 2016 (Figure 2)

· Higher interest rates (Figure 3)[24]

· A slowing U.S. economy[25]

· Reduced demand for beer[26]

Figure 3. Federal Funds Effective Interest Rate 2021-2023

Source: U.S. Federal Reserve

BACK TO THE INVENTORY DATA

In addition to the overall changes, the reported data reveal who possesses the inventory in storage. Valuable data are hiding in plain sight. The numbers paint a different picture from the graph in Figure 1.

Table 1. Hop Stocks Report data.

Source: USDA

The total inventory held as of September 1, 2023 was seven million pounds (3,175 MT) less than in 2022. That sounds like good news. It’s not all rainbows and unicorns for the hop industry though. Brewery inventory decreases were 57% of that decrease. Merchant/farmers continue to hold a disproportionate amount of inventory relative to breweries (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Percent of Inventory Holdings Held by Merchant/farmers and Breweries.

Source: USDA September 1 Hop Stocks data 1947-2023

In fact, the responsibility for holding (i.e., financing) inventory has shifted further toward the merchant/farmer. That responsibility, which soared past parity in 2014, has accelerated ever since. Today, merchant/farmers hold 4.42 pounds for every one pound of inventory held by breweries (Figure 5). That’s up from 3.79 pounds one year ago!

Figure 5. Ratio of Inventory Holdings

Source: USDA September 1 Hop Stocks data 1947-2023

The hop industry doesn’t have a hop surplus problem.

It has a CREDIT Problem!

HOP DEMAND

For years, forward contracts have been hyped as the way to estimate hop demand[27]. A merchant/farmer trying to lure a brewer into a contract will say something like: “contracts …ensure you can secure the varieties and volumes you need at a fixed price and from a consistent crop year lot”[28][29][30][31][32]. That’s not true. When the crop is short, the merchant/farmer invokes the Force Majeure clause and delivers less than contracted amount with no penalty. Contracts provide more security for the merchant/farmer than the brewery. They reduce brewery options and flexibility while locking breweries into future prices that may not reflect the future market. A more accurate statement about forward hop contracts would be: “contracts … ensure the merchant and the farmer that they have buyers locked in for the varieties and volumes they choose to produce at a guaranteed price at a specified time.” That wouldn’t convince many breweries to sign contracts though.

“Never attempt to win by force what can be won by deception.”

- Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince

This year, there have been admissions from multiple sources that hop contracts have not been working as advertised[33][34][35][36][37]. When speaking about hop contracts, Ryan Hopkins, Yakima Chief CEO, was quoted in a 2023 article by Stan Hieronymus as saying, “I don’t think it is working for brewers, and it clearly has created challenges for growers.[38]” That doesn’t sound like an endorsement of the current contract system. Contracts are not a good measure of demand. I first wrote about the con of hop contracts in August 2022 in my article, “The Con in Hop Contracts”.

A recent article by Shanleigh Thomson, called “Should You Contract Hops” pointed out some important facts about contracts. In it, Shan referred to predatory contracting practices where merchant/farmers force brewers to sign contracts for more hops than needed[39]. She rightfully pointed out that most information about contracting comes from the very people who benefit financially from them.

In addition to many forward hop contracts being signed under duress during deficits, hop contracts cost nothing to sign. They are easy to enter and difficult to escape. Forward hop contracts are based on the forecasts of the breweries signing them. Craft breweries are subject to constant changes in consumer demand. That makes them vulnerable to human error. What are the chances that their estimates about demand five years in the future are accurate? Doesn’t matter. Once they sign that contract, they’re locked in.

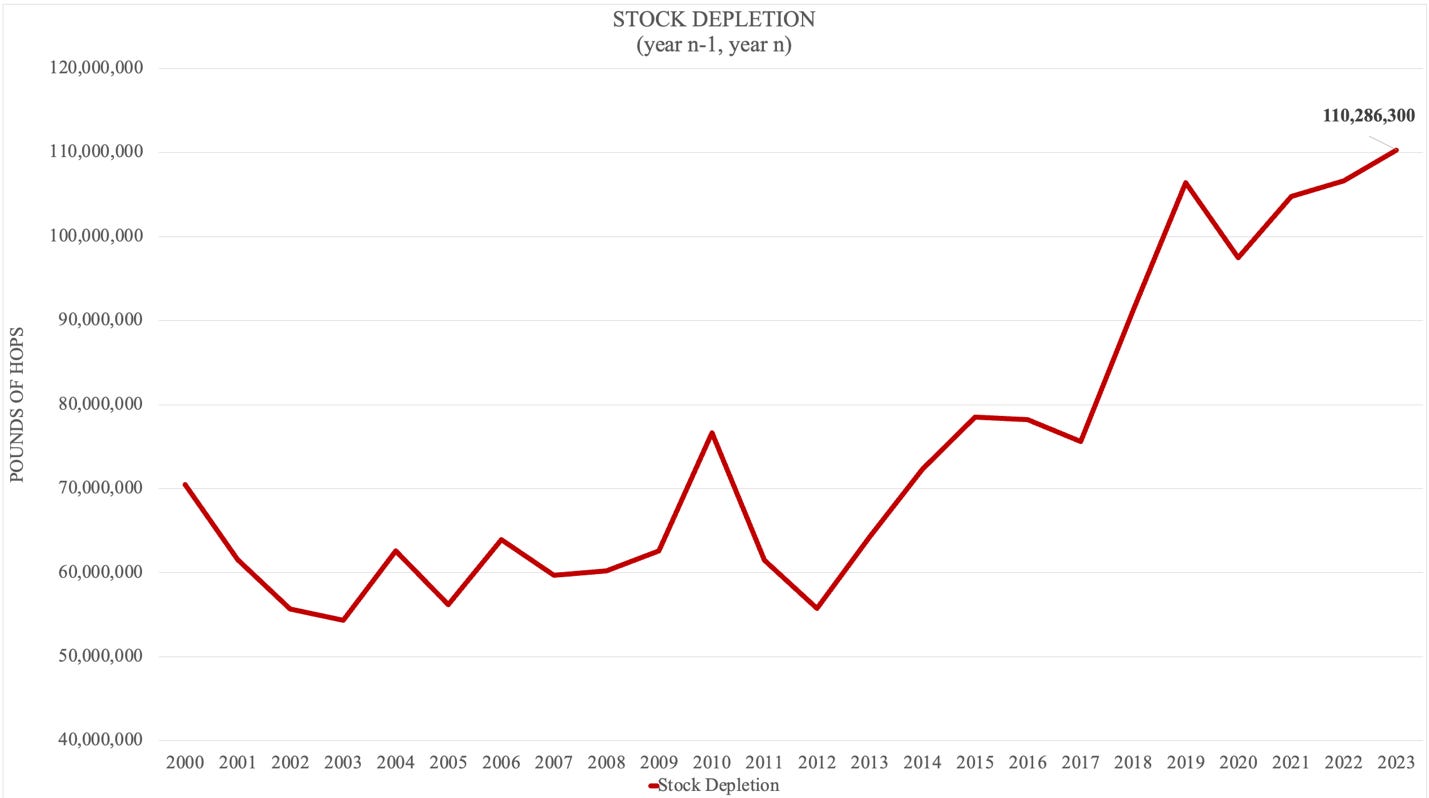

DEPLETION – A LAGGING DEMAND INDICATOR

The industry does not yet have a good way to measure future hop demand. Although it is a lagging indicator, it may be the most accurate indicator of demand for hops stored in the U.S.[40]. Annual depletion is derived from the September 1 Hop Stocks. Depletion is the quantity by which hops inventory is reduced in one year’s time. Depletion between 2022 and 2023 increased by 3.65 million pounds over the previous year’s figure (Figure 6)[41].

Figure 6. U.S. Hop Stock Depletion 2000-2023

Source: Derived from USDA September 1 Hop Stocks reports 1999-2023

HIDDEN IN THE NUMBERS

The September 1 Hop Stocks must be considered together with all the available data at the time of the report to be better understood. In June of this year, I wrote an article called, “The Hidden Truth Behind U.S. Acreage Reduction” in which I discussed how the hop industry would highlight the removal of hop acreage while downplaying the planting of different varieties in that same acreage.

My prediction was proven correct during the International Hop Growers’ Convention (IHGC) meeting in Freising, Germany in August 2023. Economic Committee data from that meeting revealed an estimate of 2,489 fewer hectares (6,147 acres) in production resulting in 982 MT (2.16 million pounds) fewer hops produced in 2023 than in 2022 (Figure 7)[42][43]. There was significant acreage of different varieties planted. Nevertheless, the effort required to execute such an acreage reduction without a corresponding market collapse is impressive and unprecedented.

Figure 7. IHGC Economic Commission Summary Report

Source: IHGC

The admission of additional U.S. plantings not reported on the summary report in Figure 7 (above) emerged during the question / answer period of the IHGC meeting. Based on the information available, it appears a net increase in the production of proprietary varieties in the U.S. in 2023 is possible. If true, this will further consolidate industry influence. In addition to that, the reductions were significant for two reasons.

Somehow two competing hop merchant companies that are primarily responsible for contracting Citra ®, HBC 394 and Mosaic ®, HBC 369 with farmers decided that 2023 was the year to reduce their contracted acreage of those varieties. That is an unprecedented coincidence[44]. Was this the result of market forces, or did something sinister happen?

There will be approximately 5.7 million pounds (2,585 MT) less Citra ®, HBC 394 and 3.3 million pounds (1,497 MT) less Mosaic ®, HBC 369 produced in 2023[45]. These data are hidden in the September 1 hop stocks report. It would be easy for the reader to misinterpret the data to think the acreage reduction efforts were unsuccessful. This is not intentional. It is a biproduct of the way the report is structured. That is a massive reduction in acreage without a corresponding market crash. The rules of the game have changed.

NOT YOUR FATHER’S HOP CYCLE

In a recent article by Stan Hieronymus, “Hops Insider: Rightsizing the Hop Market” at least one unnamed farmer claimed the current surplus means the hop cycle lives on[46]. I disagree with the anonymous hop farmer … whoever he may be. This surplus is already different from all previous surpluses. The overwhelming presence of branded products (i.e., proprietary varieties) not available to all merchant/farmers enables full-spectrum domination over production, supply and distribution of those brands. The lack of substitutability (i.e., differentiation) between varieties and brand loyalty enables runaway surpluses to be isolated. The farmer who thinks this surplus is more of the same doesn’t understand the magnitude of the change that has taken place during the previous decade. Market crashes and plummeting prices may now be avoided going forward.

It looks like farmers got what they have said they always wanted, stable higher prices. Many don’t yet realize it is a wolf in sheep’s clothing. The 2023 acreage reduction demonstrated that farmers no longer enjoy the freedom to decide which hop varieties they will produce on their land. Hop farmers were lulled into a false sense of complacency thinking their good fortune would continue forever. Some have not yet realized they are now the hop equivalent of the factories that produce iPhones somewhere in Asia. Their identity will become less relevant with time unless they are partners in the merchant company selling that variety. By 2027, Apple will produce up to 50% of its iPhones in India[47]. That’s a change from its traditional Chinese production model[48][49]. You probably don’t know the name of the Indian factories Apple intends to work with. That is because the manufacturer of the product is irrelevant. Apple has the brand value. Apple has the customer loyalty … and Apple decides with whom they share the wealth.

“One does not establish a dictatorship in order to safeguard a revolution; one makes the revolution in order to establish the dictatorship.”

- George Orwell, 1984

If proprietary varieties continue to dominate the hop industry once merchants have corrected the current supply imbalance patent owners will dictate prices to breweries. Because they are merchants and farmers, those prices will continue to increase with each passing year.

IN CONCLUSION

The hop industry forced five-year contracts on breweries for most of the past decade. Hop salespeople will argue their customers are adults and signed those contracts of their own free will. Of course, nobody pointed a gun at anybody’s head and told them to sign a contract. Many were told they would not get the hops they wanted unless they signed long-term forward contracts. That’s coercion. Inexperienced craft brewers weren’t familiar with the hop market, and they complied.

This surplus is different from previous hop surpluses for three reasons:

The brand differentiation of the varieties involved,

The surplus quantities are contracted, and

Excess production is controlled by patent owners.

Breweries purchased those varieties in part for their brand value at prices much higher than their brewing value. The expense associated with moving expensive hops out of storage makes the USDA Hop Stocks reports a measurable indicator of changing demand.

“Demand is best measured in terms of spending. You know, I think in traditional economics, it’s a mistake to measure it in terms of the quantity of goods.”

- Ray Dalio

The 2023 September 1 Hop Stocks report demonstrates that the acreage reduction efforts were effective, but the results were mixed. Merchants with contracted surplus supply have no choice but to continue to force aging inventory into the market at their premium contracted prices. They must do this to preserve contract integrity. The scope of the problem means they cannot afford to cancel old contracts and roll purchases forward or write them off as a loss. When a few brewers have a problem, that’s the norm. When a wave of breweries demanding contract renegotiations turns into a tsunami, options are limited for two reasons:

It’s challenging to sell older hop inventory at contract prices[50], and

The old inventory must retain its original book value to support the lines of credit on which hop farms and merchants rely. There is no price flexibility left.

If the hop industry marks aging hop inventory to the current market to reflect its current value, the companies holding that inventory will collapse. Their remaining option is to force their brewery “partners” to take delivery at contracted prices. Part of that strategy is to reserve fresh product for customers with no outstanding balances. To the public, the same message of partnership, relationship and cooperation will be everywhere. Now that things behind the curtain are not all unicorns and rainbows, however, the people running the companies involved are looking out for their own interests. They’ll justify their actions claiming, “it’s just business”. Hardship is a wonderful opportunity for friends (or partners) to reveal their true identity. Brewers should pay attention.

The merchants involved will rebound from the mistakes they made contracting their proprietary varieties. That may take four or five years. Once they fix the situation, they will not make the same mistakes again. These are very clever people and there is a lot of money, power and influence at stake. That may sound like a conspiracy against breweries. It’s not. Once again, the late George Carlin explained how it works in the clip below.

While the industry sorts out its problems, expect every merchant/farmer to promote the importance of forward hop contracts. They won’t recommend other options. They will promote a return to what they call more traditional and rational contracting strategies with decreasing volumes in future years. Brewers would be wise to use this momentary setback in the hop industry as an opportunity to create a more equitable hop market that serves their needs as much as it serves the needs of hop merchant/farmers.

Thank you very much for taking the time to read this article. I hope you received some value. If you did, please consider sharing it with somebody else. If you’re so inclined, you could also let me know what you think over on LinkedIn.

[1] https://www.barthhaas.com/ressources/blog/blog-article/hop-update-september-2023

[2] https://www.probrewer.com/production/ingredients/a-peek-at-the-2023-pacific-northwest-hop-outlook-with-peter-mahony-at-john-i-haas/

[3] https://www.probrewer.com/production/ingredients/hops/sustainability-and-hops-protecting-waterways-and-preserving-beer/

[4] https://www.barthhaas.com/ressources/blog/blog-article/how-do-hops-react-to-climate-change

[5] https://brewsnews.com.au/stan-hieronymus-hop-queries-december-2022/

[6] https://themessenger.com/business/how-climate-change-could-ruin-your-beer

[7] https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/12/world/europe/beer-taste-hops-climate-change.html

[8] https://www.hoptalk.live/post/too-many-hops-10000-acre-cut-needed-says-barth

[9] https://www.yakimaherald.com/news/local/business/crop-s-decent-the-market-s-not-stockpile-reduces-size-of-yakima-valley-hop-harvest/article_837b0cca-5198-11ee-a310-8772a153a07e.html

[10] https://brewingindustryguide.com/rightsizing-the-hop-market/

[11] https://www.tri-cityherald.com/news/business/agriculture/article245751170.html

[12] https://www.yakimaherald.com/news/local/hop-growers-make-changes-adjust-acreage-in-response-to-covid-19-pandemic/article_64c56709-9fca-513f-8b59-73095458b508.html

[13] https://brewingindustryguide.com/rightsizing-the-hop-market/

[14] https://beermaverick.com/how-the-pacific-northwest-hop-yards-survived-the-2020-wildfires/

[15] https://www.usahops.org/img/blog_pdf/435.pdf

[16] http://www.hmelj-giz.si/ihgc/doc/2020_NOV_IHGC_EconCommReport.pdf

[17] https://brewingindustryguide.com/rightsizing-the-hop-market/#:~:text=Haas%20CEO%20Alex%20Barth%20estimated,the%20Czech%20Republic%20even%20grows.

[18] https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2020/10/26/how-a-subscription-business-can-increase-business-valuation/?sh=54675d25b2e7

[19] https://www.brewersassociation.org/association-news/ba-insider-growth-craft-beer-segment-sky-limit/

[20] https://www.goodbeerhunting.com/sightlines/2017/3/29/brewers-association-calls-20-by-2020-goal-a-long-shot-at-this-point

[21] https://www.brewersassociation.org/statistics-and-data/national-beer-stats/

[22] This is true if a contract is with an American, Canadian, British or Australian company, this rule of thumb also applies. In general, it does not apply to contracts with customers from other countries, but that is reviewed on a case-by-case basis. The bank considers contracts in other foreign countries outside the reach of the legal system, or prohibitively expensive to pursue in case of default.

[23] https://mises.org/wire/banks-create-money-out-thin-air-what-could-possibly-go-wrong

[24] https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FEDFUNDS#

[25] https://www.usbank.com/investing/financial-perspectives/market-news/economic-recovery-status.html

[26] https://slate.com/business/2023/07/beer-sales-decline-explained-hard-seltzer-craft-beer.html

[27] https://www.hops.com.au/how-to-secure-your-future-hop-supply/

[28] https://daily.sevenfifty.com/why-brewers-should-be-going-to-hop-harvests/

[29] https://www.yakimachief.com/commercial/hop-wire/cascade-centennial-contracting

[30] https://bsgcraftbrewing.com/about-us/

[31] https://shop.barthhaasx.com/s/hop-contracts

[32] https://www.crosbyhops.com/shop-hops/hop-contracts

[33] https://www.yakimachief.com/commercial/hop-wire/2023-usda-hop-acreage-report-update

[34] https://americanhopconvention.org/assets/img/misc/2023-Convention-Presentation-Alex-Barth-Merchant-Panel.pdf

[35] https://www.hoptalk.live/post/too-many-hops-10000-acre-cut-needed-says-barth

[36] https://beernouveau.co.uk/looking-towards-2023/

[37] https://www.shanferments.com/blog-resources/shouldyoucontract

[38] https://brewingindustryguide.com/rightsizing-the-hop-market/

[39] To be fair to Shan, she didn’t use the word “force”. As somebody with experience forcing brewers to sign long-term contracts, I paraphrased because I believe that more accurately describes the way the system works.

[40] Even the USDA hop stocks reports are not perfect as those data are voluntarily reported by those who store hops. There are no mandatory reporting requirements for any statistics in the U.S.

[41] Depletion is derived by taking the U.S. September 1 hop stocks figure for the previous year (Sn-1), adding the crop for the previous year (Cn-1) and then subtracting the current year’s September 1 stock figure (Sn). That would be represented by the following formula. D = (Sn-1 + Cn-1) – Sn

[42] The large acreage difference resulting in a relatively small reduction in production is due to low yields in 2022 and average yields in 2023.

[43] http://www.hmelj-giz.si/ihgc/activ/aug23.htm

[44] For example, in 2001, farmers formed something they called the Hop Alliance. As a group, the Hop Alliance agreed to reduce acreage. The result was that some members of the group reduced acreage while others planted leading to no net reduction.

[45] The 2023 crop estimates for Citra ®, HBC 394 and Mosaic ®, HBC 369 were calculated by combining the USDA June Strung for Harvest figures together with a five-year average of yields for those varieties by state. The result will likely be less than these figures since the five-year average includes the low yields of 2019 and 2022 for the Citra ®, HBC 394 variety and the low yields of Mosaic ®, HBC 369 in 2020 and 2022.

[46] https://brewingindustryguide.com/rightsizing-the-hop-market/

[47] https://www.scmp.com/tech/big-tech/article/3216055/made-india-iphones-surge-apple-moves-production-away-china#

[48] https://www.scmp.com/tech/article/3234153/worlds-largest-iphone-factory-ramps-hiring-efforts-china-ahead-apples-launch-new-handset

[49] https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/11/business/dealbook/foxconn-worker-conditions.html

[50] https://thebrewermagazine.com/working-hop-contracts/