A Deal with the Devil

Craft brewers have signed a deal with the devil. I’m not talking about the contracts they have with hop merchants … although that would probably be an appropriate metaphor. I’m talking about the proprietary varieties in those contracts. I’ve been told by quite a few brewers that there are two reasons for the current trend in hop usage:

1) There are a lot of inexperienced brewers out there. Big hoppy IPAs are popular among brewers because they can hide a lot of sins (e.g., diacetyl[1]). They’re ready for sale quickly and they capitalize on the current passion by the consumer for hops, and

2) Varieties like Citra®, HBC 394 are easy to use because their flavor profile is simple, which apparently makes the brewing process less susceptible to off flavors.

I’m not a brewer, but when brewers tell me those sorts of things, I believe them. I can’t evaluate how much easier it is to brew with one variety versus another. That seems to me like a rather subjective thing as I imagine there are a million problems that can occur in the brewing process. It’s hard for me to imagine that using a particular variety is a silver bullet that solves all these problems.

Let’s look at the facts. Brewers Association statistics reveal that the number of U.S. craft brewers increased 321% over the past decade, from 2,252 in 2011 to 9,247 in 2021[2]. Even at the beginning of that explosive decade of growth, there were already concerns over the rapid growth of the craft industry and what the influx of inexperienced brewers would do to the industry[3].

If those concerns were warranted in 2011, I can’t imagine the situation today. Brewers who started within the past 10 years are probably not aware of the history of the industry. I doubt they understand the relationships between merchants and farmers beyond what they’ve been told. The purchase of proprietary varieties en masse has changed industry dynamics.

What does that mean? In a nutshell it means prices will remain relatively stable at levels far above the long-term average price (Figure 1)[4] unless the situation changes. Brewers, however, are paying with much more than money for their hops. Proprietary varieties represent a Faustian bargain with the potential to change the global brewing industry … forever. Forever is kind of a long time. If that sounds like hyperbole to you, continue reading.

Figure 1: U.S. Season Average Prices 1948-2020 Adjusted for Inflation Using CPI.

A Faustian Bargain

If you’re not familiar with the story of Doctor Faust or you’ve never heard the term “Faustian Bargain”, In 1592, English playwright, Christopher Marlowe produced the first dramatization of the German legend of Faust called, “The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus”[5][6]. In it, Faust signs a contract with a demon named Mephistopheles (insert your favorite merchant salesperson’s name here). He sells his soul to the devil in exchange for supernatural powers, which last for 24 years. An hour before the devil came to collect, he realized the true cost of what he had done, and tried to repent, but it was too late. For a fun modern-day summary of this story, you can Check out this video.

Craft breweries that use patented and trademarked variety names on their labels have traded their independence to use varieties they think will increase their sales. In the process, they have facilitated greater concentration of power within the hop industry.

A simple Google image search for “Simcoe IPA” (Figure 2) and “Citra IPA” (Figure 3) reveals that putting the name of a proprietary variety on a label is common[7].

Figure 2: Google image search results for the term “Simcoe IPA” on August 5, 2022.

Figure 3: Google image search results for the term “Citra IPA” on August 5, 2022.

If you own one of the breweries that produced one of the beers pictured above, this is not an attack on you. You are part of a larger trend with serious consequences though. Remember, the people that own the companies that own proprietary hop varieties also have financial interests in hop farms and/or merchant companies. It’s wonderful that brewers trust the hop industry, but they should question if hop farmer / merchant interests align with brewer interests. Some certainly do. As a merchant, I’ve seen that farmers often want to receive more money per pound while brewers want to pay less. In other words, from my experience, it appears their interests are diametrically opposed to one another … at least with respect to money. The challenge comes when the market moves significantly up or down. Brewers demand contract renegotiations and, believe me when I tell you that from there it can be a downward spiral. Proprietary varieties enable their owners to manage the supply of their varieties. If they can do that, they have a chance to keep prices at “sustainable” levels. But who decides what’s sustainable?

All of this is completely legal. A U.S. Supreme Court decision from 1980[8] established the precedent that enabled a handful of corporations to take control of the world’s food supply[9]. It has taken decades, but a similar fate might now await the hop industry if brewers continue to focus on buying a handful of proprietary varieties from behemoth hop companies with global reach. Isn’t the mantra of the craft beer industry something to do with local production, or is that just for marketing purposes?

Monsanto (now Bayer[10]) uses patent law to control approximately 95% of the soybean market and 80% of the corn market in the U.S.[11]. Companies that own hop IP can be expected to pursue similar actions if any such violations occur. Much like soybean or corn farmers, fewer hop farmers own the plants on the land they farm today than just 10 years ago and with that ownership goes the power. Proprietary varieties in 2021 accounted for over 70% of U.S. hop acreage[12]. Many farmers sign licensing agreements with a variety’s owners that reduce their autonomy with regards to the production of the varieties they produce. That’s the price they have to pay to play.

Hyperbole?

The purchase en masse of proprietary varieties has bestowed a disproportionate amount of power upon a few individuals who own popular proprietary hop varieties. Naturally, this trickles down to the companies in which they have financial interests. In the past, merchants and farmers routinely undercut competitors’ prices to get market share. That creates a more efficient and streamlined market. Today, that’s not possible. I’m not even talking about the royalties a farmer must pay per pound of proprietary hops he/she grows. I’m talking about competition. Varieties are no longer perceived as homogenous due to their brand value. Most proprietary varieties are not independently sold (although there are a few exceptions to this rule). The reduced number of independent sales outlets has reduced the possibility of price-based competition. As the industry consolidates further, expect this trend to increase.

Proprietary varieties bring with them a great new way to compete for market share … at the source. The owners of the proprietary varieties (who also have financial interests in farms and merchant companies) can deny their primary competitors direct access to their IP. I know merchants that felt they were used to developed markets for U.S. proprietary varieties overseas between 2010-2015 only to later be denied the renewal of their contracts. It was a brilliant, albeit devious, strategy that grew market share around the world using other people’s time and effort and subsequently centralized control of the operation.

Competitors are left with secondary supply chains (i.e., through other merchants or brewers) to source these varieties if they wish to keep a customer who will take nothing else. They are less price competitive. Those varieties were used to create a competitive advantage for the firms that market them. It makes sense that a firm that develops proprietary varieties whose owners also own shares in hop merchant firms would want to create a competitive advantage for the merchant companies in which their owners have a financial interest. These are not philanthropic entities. They exist to make a profit … and based upon their growth we can presume they do quite well. How well is a subject for another article.

“And ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free.”

- John 8:32

Is it Really that Bad?

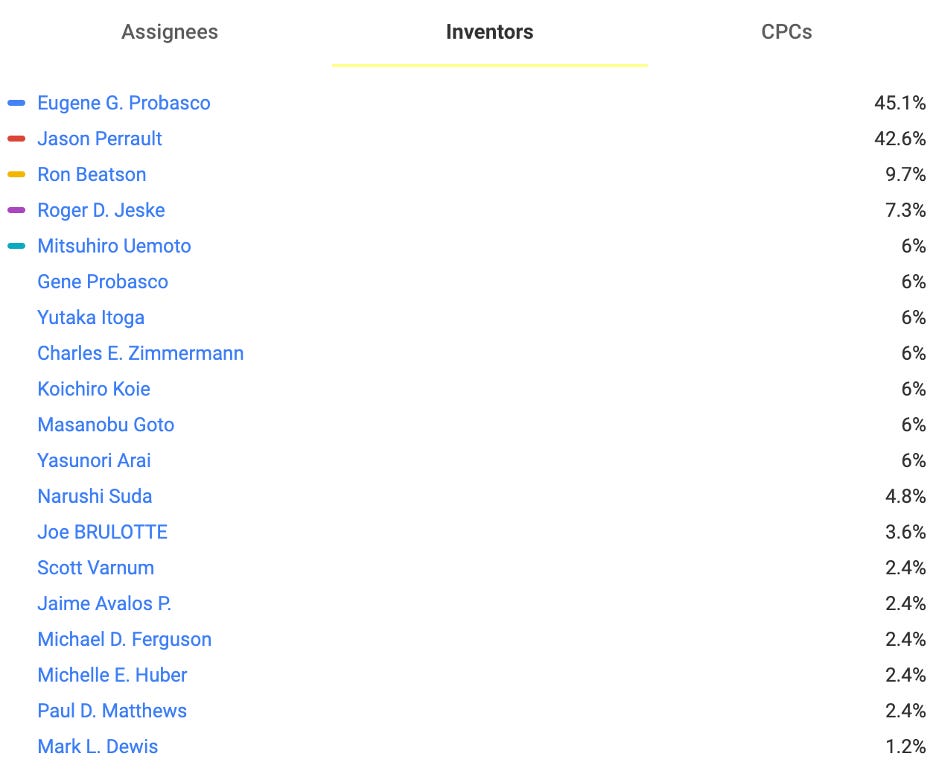

For those of you not familiar with patents, they have inventors and assignees. A Google patent search for the term “hop plant named” provided a list of patent assignees (Figure 4) and patent inventors (Figure 5)[13].

Figure 4: List of Patent Assignees Resulting from a Google Patent Search “Hop Plant Named” on August 5, 2022.

Figure 5: List of Patent Inventors Resulting from a Google Patent Search “Hop Plant Named” on August 5, 2022.

A much better way to understand who influences the current U.S. varietal makeup, however, is to look up the patent details on each variety listed by the USDA in the 2021 National Hop Report[14]. Below, I’ve grouped the patents by assignee in alphabetical order (Click on the variety names to see the online patent record for that variety).

List of Proprietary U.S. Hop Varieties Reported Separately by the USDA.

PATENT ASSIGNEE: American Dwarf Hop Association, LLC

TRADEMARK: CLS FARMS, Inc.

El Dorado®†[19] (Trademark: DEAD/CANCELLED)

PATENT ASSIGNEE: Hop Breeding Company, L.L.C. **

PATENT ASSIGNEE: Jackson Hop, LLC

PATENT ASSIGNEE: Oregon State University

PATENT ASSIGNEE: S.S. Steiner, Inc.

EUREKA!™ †[37] - No patent found, active trademark record found instead.

PATENT INVENTORS (WITH NO ASSIGNEES)

Amarillo® VGXP1[38]* - Inventors: Paul A. Gamache, Bernard J. Gamache, Steven J. Gamache

OTHER VARIETIES FOR WHICH NO RECORDS WERE FOUND:

Ahtanum††

Tomahawk††

Zeus††

* These patents were filed more than 20 years prior to the time of this writing.

** Patented varieties listed together in the section with the Hop Breeding Company LLC, (HBC) include those issued to John I. Haas, Inc., Yakima Chief Ranches, L.L.C., Select Botanicals Group, LLC, and Hopunion USA due to various name changes and/or mergers and acquisitions over the years in question.

† Only trademark records could be found.

††No patent or trademark records could be found using Google patent search. That does not mean they do not exist. There are other terms that could have been used to file the patent and it was not possible for me to search through the thousands of patents owned by hop industry members in the time allotted.

Note: Some of the patents for varieties in Figure 6 were originally filed more than 20 years ago. Those are in red. In theory, competing producers could create generic versions of the same product. Some suggest it is the obligation of the original patent holder to facilitate this[39].

The list above is not intended to be an exhaustive list of patented or trademarked U.S. hop varieties. I only included varieties reported by the USDA in its 2021 year-end report[40]. There are MANY more (you can find them on google patent search for yourself here). The greater degree of control and profit incentivizes private hop breeding companies to invest further in innovation because they can protect and enforce their rights[41]. The number of patented hop varieties on Google not listed above, which I’d recommend you look at, demonstrates a clear direction for the future of the hop industry.

There is nothing illegal about companies managing the monopolies their proprietary variety represent. A monopoly, after all, is the purpose of a patent … as discussed in one of my previous articles, “Has a Cartel Taken Over the Hop World?”.

Brand and marketing value seems to be as important as the brewing value today. Some brewers are so eager to get the newest thing they specifically ask for experimental varieties that haven’t even been named yet. That seems a bit like the tail wagging the dog, but ok. If monopoly control of a key ingredient sounds appealing, brewers can just continue the status quo. If, on the other hand, they would be interested in a hop industry whose direction is not influenced by a few individuals, all they have to do is buy more public varieties and rely on their creativity more than brand names.

Concentration

The limited number of companies developing new proprietary varieties (i.e., brands) represents a concentration of power the industry has never seen. It is possible to measure this concentration by using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI). The U.S. Department of Justice uses the HHI during reviews of mergers and acquisitions within an industry to determine the effect that merger will have on competition and assess potential anti-trust risks[42]. That is a topic for another article. Below is a taste of what to expect from that article (Figure 6).

Figure 6: HHI Values for U.S. Proprietary Variety Production 2000-2020.

Source: author’s own calculations based on USDA NASS National Hop Report data 2000-2020.

Locked In?

The fact that most craft brewers request the same five aroma varieties from their hop merchants is not in and of itself a problem. The problem is that those five varieties are proprietary. If the five U.S. varieties were, for example, Cluster, Cascade, Chinook, Nugget and Galena, that would guarantee a competitive environment because those varieties are all public. With a public variety, anybody can grow and sell a variety at any price. Not so with proprietary varieties. Public varieties still constituted a majority of the U.S. hop industry as recently as 2016. The industry reached a tipping point in 2017, as demonstrated in USDA statistics, when proprietary varieties increased to 51% of U.S. acreage[43]. Figure 6 (above) demonstrates the rate at which the concentration in the industry increased between 2017 and 2020. By 2021, public varieties accounted for roughly 22% of U.S. acreage.

The absence of public varieties leaves brewers vulnerable to something called “Vendor Lock-In”. Forbes Councils Member, Peter Zaitsev, explains, that although there are some benefits to being locked into a vendor relationship, the process creates dependency on the vendor and vulnerability for themselves. This leaves the customer at the mercy of their vendor’s decisions[44]. Since I began sharing my thoughts on the state of the hop industry just one month ago, several people have shared their experiences with me. I appreciate and want to thank everybody who has reached out to me so far and would like to encourage others to do the same.

I’ve heard similar stories from different parts of the world. It seems merchant salespeople selling proprietary varieties group public and private varieties together in package deals at competitive prices. If, however, the customer wants to source their public varieties elsewhere, prices for the remaining proprietary varieties increase making the deal much less attractive[45]. The decision not to pay higher prices and buy public and private varieties from one vendor, of course, is a free choice made by the customer. That’s a very clever strategy. That’s a method I would use if I was a hop merchant that wanted to gain market share beyond the influence of the proprietary varieties I had to offer. Merchants know how price sensitive the market is.

By committing wholeheartedly to patented and trademarked varieties and locking themselves in with specific vendors, brewers trade their independence for short-term profit. They place their trust in entities in the hop industry. A beer made with a proprietary variety whose name is on the label and whose production they cannot control represents vulnerability, dependency and risk. Caveat Emptor!

Winter is not far off … literally and figuratively. We can clearly see the effects of these types of decisions with an extreme situation like that in Ukraine. Russia can, if they choose, exert a disproportionate influence over Germany when the temperatures drop due to Germany’s reliance on Russian energy. Germany is trying to reduce their vulnerability now that their risk has become clear. Just one year ago, the situation was unimaginable to most, although there were people sounding the alarm[46]. Brewery dependence upon proprietary varieties represents a similar risk. It’s difficult today to imagine what a “hop winter” might look like. It’s easy to think winter will never come or brush that off as somebody else’s problem. The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Summer always turns to fall, and winter always looms on the horizon. It’s a story as old as recorded history. God told Noah to build the ark before the rains came.

The True Cost of Proprietary Varieties

The potential takeover of the hop industry by a few people may seem unrealistic in 2022. The cost of the loss of independence, freedom, and a free-market system, however, are externalities[47]. They are not priced into the equation. Prices for proprietary varieties would be much higher if they included externalities. Perhaps if Doctor Faustus had weighed the true cost of his deal before signing his contract, he would have acted differently. Hindsight is 20/20. Brewers have that chance still. When Faustus made his deal, the day of reckoning seemed far off. The brewing industry today is in a similar situation, but the day of reckoning is rapidly approaching. It was only in the final hour when Doctor Faustus realized the consequences of his decision. Will brewers wait as long. Spoiler alert! … By the time he realized his mistake, it was too late for Faustus. He spent the rest of eternity in hell.

I hope you found this article interesting. If you have information about the patent records I was unable to find (or any other documents you think might be of interest) and would like to share that with me, I would be grateful.

If you haven't already, I hope you’ll consider subscribing. I'll be publishing something around the 1st and 15th of each month.

[1] https://www.homebrewtalk.com/threads/diacetyl-cover-up.464001/

[2] Please refer to the Historical U.S. Brewery Count at: https://www.brewersassociation.org/statistics-and-data/national-beer-stats/

[3] https://www.beeradvocate.com/articles/6263/the-craft-beer-roller-coaster/

[4] I’ve used that chart in previous articles. If you’re getting tired of seeing it, I apologize, but its importance cannot be overstated and offers perspective to the recent pricing trend.

[5] https://www.college.columbia.edu/core/content/tragical-history-life-and-death-doctor-faustus-christopher-marlowe-1620

[6] Image source: via Wikimedia Commons. Image in the Public Domain.

[7] These images are from two Google Image searches conducted on August 5, 2022.

[8] https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/447/303/

[9] https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2008/05/monsanto200805

[10] https://media.bayer.com/baynews/baynews.nsf/id/Bayer-closes-Monsanto-acquisition

[11] https://www.cleveland.com/nation/2009/12/monsanto_uses_patent_law_to_co.html

[12]https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Regional_Office/Northwest/includes/Publications/Hops/2021/hops1221.pdf

https://patents.google.com/?q=(%22hop+plant%22)&oq=(%22hop+plant%22)

[14]https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Regional_Office/Northwest/includes/Publications/Hops/2021/hops1221.pdf

[15] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/ec/ba/45/14567a6fd9b81d/USPP27957.pdf

[16] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/10/96/03/69796d9a4ad0be/USPP27958.pdf

[17] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/f3/1c/05/283598704477f5/USPP27779.pdf

[18] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/58/b3/32/c5962ba247ce4a/USPP18039.pdf

[19] https://uspto.report/Search/cls%20farms

[20] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/99/f4/90/aa9044e78728a7/USPP21289.pdf

[21] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/9a/1d/c0/6e8edecce22cc6/USPP10956.pdf

[22] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/68/77/4d/bd5464eea34120/USPP25899.pdf

[23] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/b6/92/e6/6c335e4f5811c2/USPP25874.pdf

[24] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/e5/07/6d/b0f12eb9c5ad64/USPP24125.pdf

[25] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/24/89/53/7bcb5adf486912/USPP15663.pdf

[26] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/88/ae/f0/fe2f713b26db84/USPP29850.pdf

[27] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/dc/b1/97/ab046514516615/USPP29577.pdf

[28] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/50/26/f4/74ab1cd8004b5c/USPP12213.pdf

[29] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/9a/0b/4c/c997379ecd19c1/USPP30764.pdf

[30] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/04/9b/d5/42d151f2ad4c0d/USPP12404.pdf

[31] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/27/9f/07/b263fff2a0ace3/USPP30937.pdf

[32] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/b7/2b/40/190c337737703c/US20190208680P1.pdf

[33] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/77/90/26/946f8b4f94614e/USPP20200.pdf

[34] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/4d/98/65/dd5786d0dfa8d5/USPP18602.pdf

[35] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/a6/bc/f1/25dd64e8182a71/USPP24299.pdf

[36] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/55/76/ee/1445f9e2c1fab1/USPP20227.pdf

[37] https://uspto.report/TM/88578234

[38] https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/92/91/ab/7085bd4cdd4846/USPP14127.pdf

[39] https://www.craftbrewingbusiness.com/featured/hazy-ip-understanding-patents-and-trademarks-through-hops/

[40] The USDA only reports acreage and production for varieties that meet the three-producer threshold. Any variety produced by fewer farmers is reported in aggregate in the “other” or “experimental” categories.

[41] Bugos G., Kevles D. (1992): Plants as Intellectual Property. Osiris, 7: 74-104.

[42] https://www.justice.gov/atr/horizontal-merger-guidelines-08192010

[43] https://www.usahops.org/img/blog_pdf/105.pdf

[44] https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2021/03/30/understanding-the-potential-impact-of-vendor-lock-in-on-your-business/?sh=5321f12c5455

[45] Thank you very much for the individuals who shared that with me. I value your confidence and the quality of the information you provided. I appreciate and will protect your confidentiality and trust in me. For anybody else wishing to share interesting experiences, please do not hesitate to reach out.

[47] https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/basics/external.htm