How do you know the price of hops? Because a merchant told you. That's the thought I ended my previous post with. It's one of the reasons why brewers more than anybody should be interested in subscribing and understanding how the hop market works. Ultimately, it's brewer money that makes the wheels on all those tractors go round.

Do farmers and brewers have similar goals? From my experience working between the two groups as a merchant, farmers usually want higher prices and longer contracts. Brewers usually want shorter commitments and lower prices. Do farmers get along with one another? When a farmer has a fire on the farm, it’s great to see how their neighbors do what they can to help him get the crop in. There’s a kinship there that you must witness to appreciate. There is, however, no shortage of rivalries in the hop industry the rest of the time. Some farmers have ambitions for their farms to be larger than their neighbors while others are concerned with their relevancy among their peers.

Quite a few farmers in the Yakima valley are related. Natural alliances formed during decades of difficulty bringing with them strong rivalries. Power today is so concentrated. That has reduced the options of the truly independent hop farmer and has silenced opposition to the handful of people in charge. A lopsided power structure has emerged, giving the advantage to a handful of individuals while relegating the rest to do what is best for their farm.

“If a man owns land, the land owns him.”

- Ralph Waldo Emerson

One company essentially controlled by four families, the Hop Breeding Company[1], enjoyed seeing their varieties on more than half of U.S. acreage in 2021[2]. Between 2011 and 2021 Pacific Northwest hop farm acreage increased 104.3% (31,085 acres or 12,585 hectares)[3]. Proprietary varieties accounted for most of that increase. That means the owners of those varieties now influence those acres.

The largest U.S. farms today produce between 3,000 - 5,000 acres (1214 - 2024 hectares) with many farms producing over 1,000 acres (404 hectares). A hop farm must produce hops to exist ... obviously. That's not a position of strength from which to negotiate. Complicating the situation is that American hop farms run on debt. When hops are proprietary, the owners of the hops decide who gets the contract to produce them. In the U.S., in 2021, according to the USDA, over 70% of all hop acreage was proprietary[4]. A grower who was very candid with me shared that he censors what he says and does for fear of losing the opportunity to produce certain proprietary varieties.

All of this is brought about by the disproportionate demand by craft brewers for proprietary varieties. This is not an attack on proprietary varieties. They're great. This is simply an attempt to increase awareness about the consequences of their actions with regards to the power dynamic in the hop industry.

If this is news to you, or if you're skeptical, try to find proprietary varieties that have an "HBC" in their name that are sold by the competitors of that company's owners[5]. You'll have to dig a bit to find out the companies owned by that company's owners to figure out who their competitors are[6][7][8]. It won't take long to figure out who the most influential hop growers are in 2022. We'll get into that in a future article so subscribe and stay tuned. The merchant companies in which these individuals also enjoy ownership together with the channel partners of those companies have access to those varieties. Try to find those varieties on offer on their competitors' web sites. You probably won't. There are a few exceptions to this rule as there are in any situation, but in general a company doesn't offer its competitors' proprietary products … because they don’t have access to them.

When I was a hop merchant, I played the game of self-censorship. I had to get the varieties I thought we needed. Once upon a time, when I was director of Hop Growers of America, I commented on pesticides publicly. A board member promptly threatened to have me fired if I ever mentioned pesticides again. You don't bite the hand that feeds you. So, I never mentioned pesticides again. Self-censorship has been a staple of the hop industry for a long time. Money buys contentment and prices have been higher than average for nearly 10 years so nobody is complaining. Independent U.S. hop farmers (i.e., those who don't own the most popular proprietary varieties) should be most concerned about the proprietary trend. Their contracts are more likely to be cut when demand decreases.

On a tour through Europe in June 2022, I spoke with hop farmers and merchants in several countries. They were already concerned about the direction of the industry and their future role in it. They shared with me they simply cannot compete head-to-head with the popularity of U.S. proprietary hop varieties. The low prices they receive for their public varieties are slowly draining their equity. Their proprietary varieties have not gained traction and they lack the global distribution channels of their American counterparts. They were concerned that inflation would jeopardize their very existence.

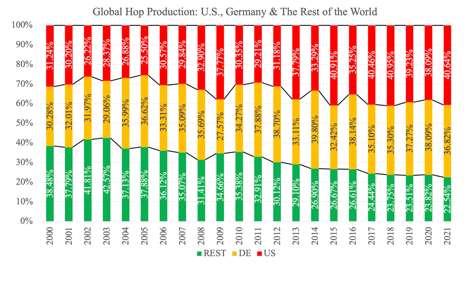

As U.S. proprietary variety production has increased, hops grown in countries other than Germany and the U.S. in 2021 comprised almost half the proportion of global acreage they did in 2003 (Figure 1). If you're a brewer, it might be a bit clearer already how this concentration of power within the hop industry might affect your future selection? If not, that's ok because there are still quite a few pieces missing from the puzzle that we'll fill in so stay tuned.

Figure 1: Change in the Percentage of Global Hop Production for the U.S., Germany and the Rest of the World between 2000 and 2021.

Source: USDA NASS National Hop Report (NHR) 2000-2021

Brewers should be concerned about the future of hops. Ironically, as companies market their own products, the expansion of proprietary varieties appears it will bring a future with less diversity, sustained higher prices and fewer varieties from which to choose[9].

In the June Acres Strung for Harvest report by the USDA last month, proprietary acreage decreased slightly for the first time in years[10]. Acreage of several public varieties increased. While this is promising, it is not a future brewers will be thrilled to watch unfold. I'll explain why in greater detail in the article where I analyze the June numbers in detail.

If you want to hear what's going on or get an unbiased opinion, subscribe and support the MacKinnon Report. What does "support" mean? It means subscribing, which is free. These articles will always be free because I enjoy writing.

If you liked something you've read, please share it with somebody you think might also find it interesting. I already have 33 topics lined up to discuss in depth in coming articles. If you have a topic you would like to read about, please let me know. You can DM me on one of the social media platforms.

I'll be publishing something around the 1st and 15th of each month so as not to fill up your inbox. If you haven't already, I hope you will consider subscribing.

These articles are free. If, however, you found some value in what you read and would like to provide some value in return, you can donate here. There’s no obligation to donate if you cannot afford it.

Cheers!

[1] https://www.hopbreeding.com

[2] https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/Todays_Reports/reports/hopsan21.pdf

[3]https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Regional_Office/Northwest/includes/Publications/Hops/2021/hops1221.pdf

[4]https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Regional_Office/Northwest/includes/Publications/Hops/2021/hops1221.pdf

[5] https://www.hopbreeding.com

[6] https://www.yakimachiefranches.com/about/

[7] https://www.yakimachief.com/commercial/about-us/our-company

[8] https://www.johnihaas.com/about-us/

[9] https://www.huffpost.com/entry/high-price-of-monopoly-wh_b_1291603

[10]https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Regional_Office/Northwest/includes/Publications/Hops/2022/HOP_06.pdf