The secret behind who controls the hop industry

Confusion, consolidation and transparency in the U.S. Hop Industry

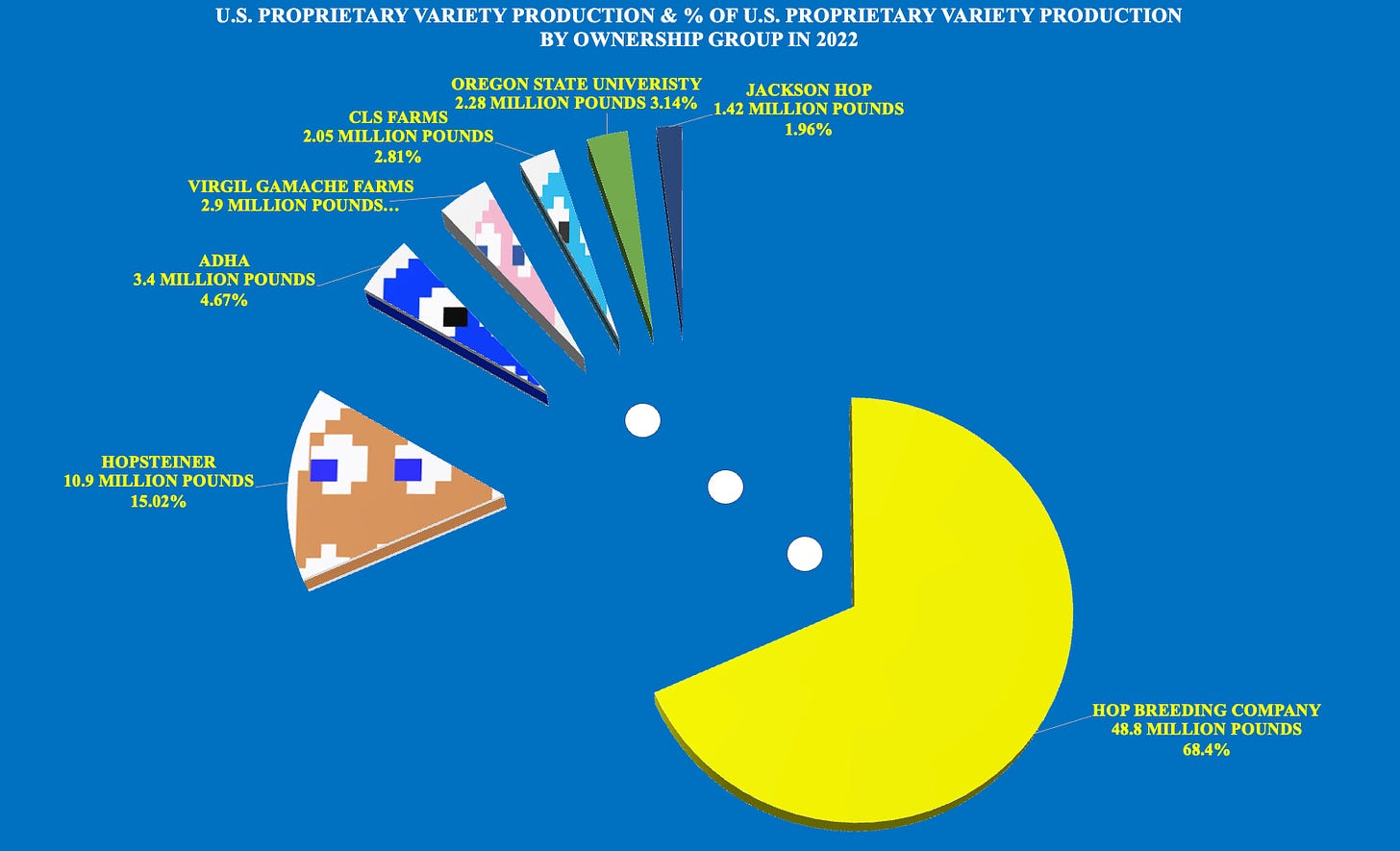

There are a handful of varieties brewers have wanted for the past decade. You know the ones. Only licensed farmers can grow them. Only licensed merchants can sell them. Not all brewers understand that because those varieties are proprietary some farmers and merchants are excluded. There is nothing inherently wrong with proprietary varieties. They’re great … in moderation. By 2022, according to the USDA, proprietary hop variety production represented 71.82% of all hops produced in Washington, Oregon and Idaho. Very few have considered the impact that the total domination of the industry by proprietary varieties has had over the past 20 years. I believe the lack of brewer awareness of the impact of proprietary varieties on the industry is no accident. The details about who owns those varieties are hiding in plain sight. Ownership of 68.4% of 2022 proprietary variety production belonged to just one company (Figure 1)[1].

Figure 1. Market share of U.S. proprietary hop variety production by ownership group.

Source: USDA

THE COMPANIES THAT OWN YOUR HOPS

Hop Growers of America (HGA) reported in their 2022 Statistical Report that proprietary varieties reported individually occupied 68.11% of acreage in Washington, Oregon and Idaho. The “other” and “experimental” category represented an additional 7.54% of acreage[2]. A significant portion of “other” and “experimental” acreage has been proprietary over the past 20 years. That information remains concealed because not all varieties meet the USDA threshold for independent reporting.

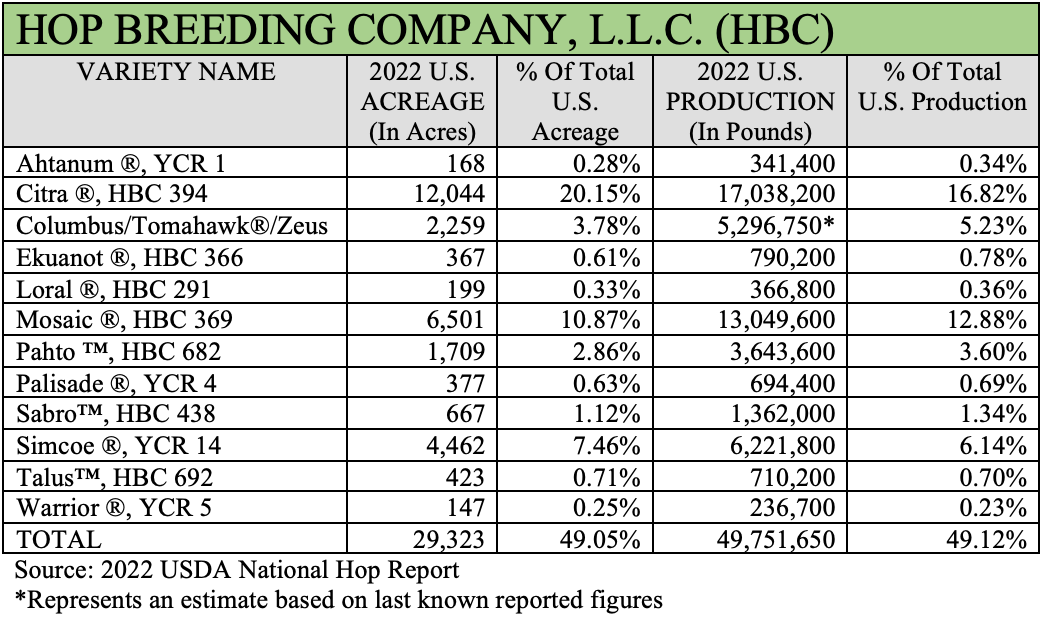

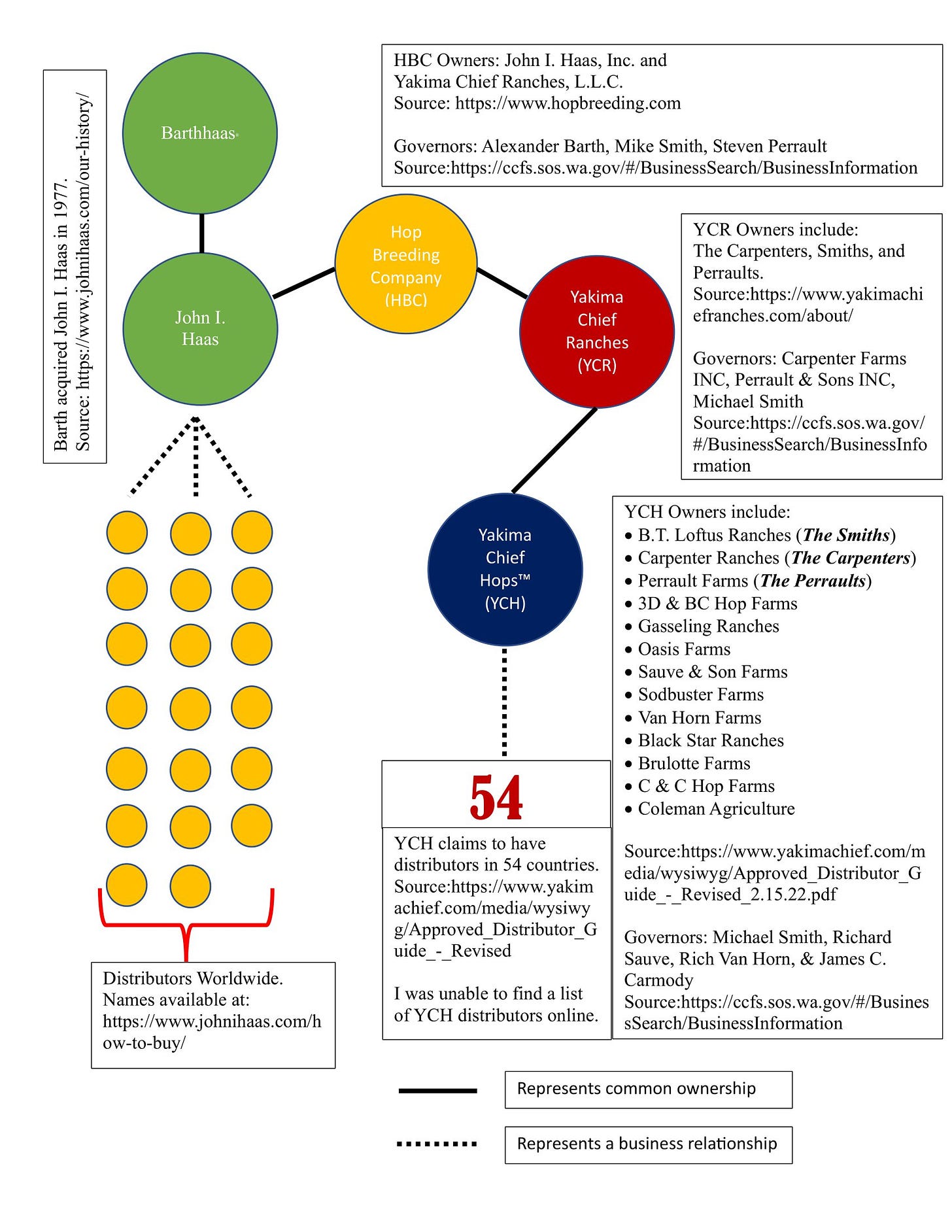

The Hop Breeding Company, L.L.C. (HBC) owned the Intellectual Property (IP) for the most widely planted American proprietary varieties (Figure 2) [3]. In 2020, the varieties owned by the HBC peaked at 50.40% of production and 49.01% of acreage. Since then, it has declined every year[4]. Due to the current surplus, acreage and production of these varieties are forecast to decline in 2023[5].

Figure 2.

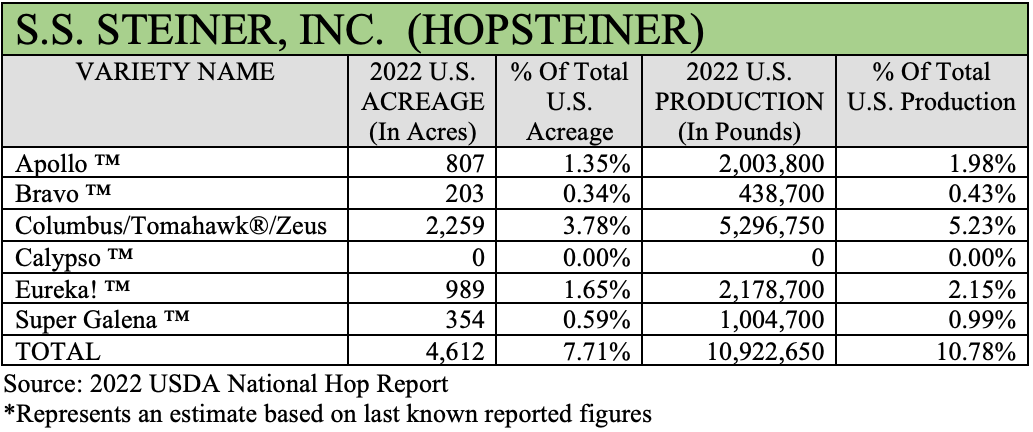

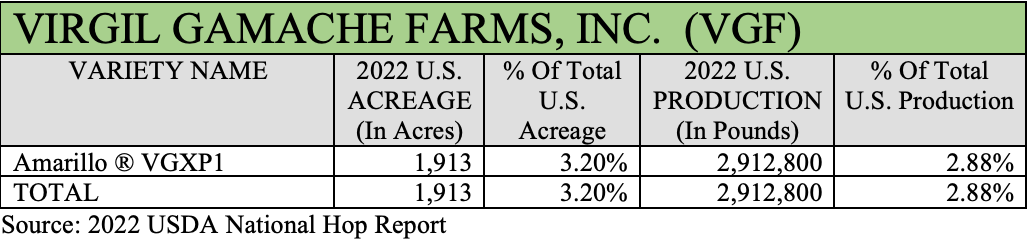

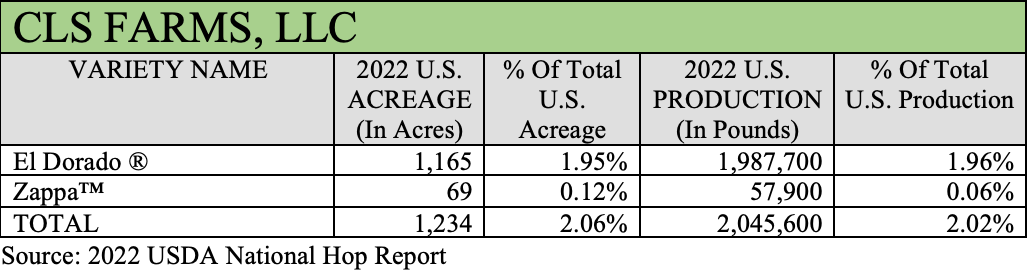

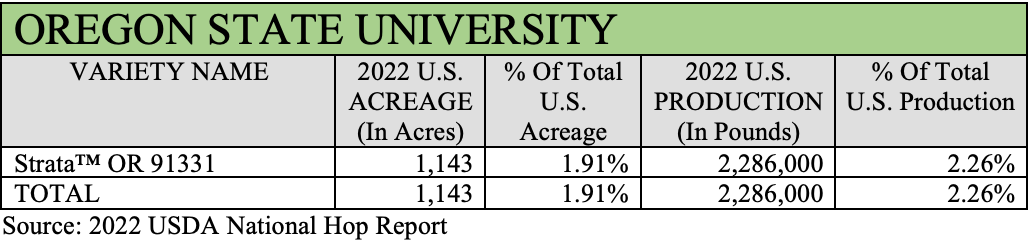

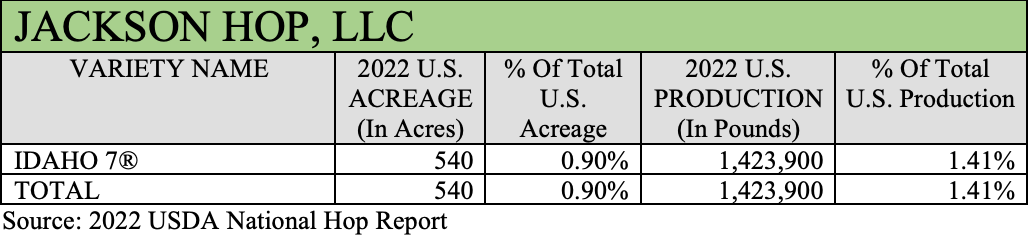

HBC is the most prolific and successful creator of proprietary hop varieties in the U.S. They are not alone. Many other companies have sought to compete in the proprietary space head-to-head by creating their own branded varieties (Figures 3-8). As of 2023, none have enjoyed the success of the HBC.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Figure 7.

Figure 8.

“Quis Custodiet Ipsos Custodes?”

“Who is watching the watchers?”

BUT … WHO OWNS THE COMPANIES THAT OWN YOUR HOPS?

That is the more interesting question. Most companies are straight forward when they claim the ownership of their intellectual property (IP). They share the origin stories of the proprietary variety brands they market[8][9][10][11]. The clarity and transparency they provide is valuable.

The ownership of varieties created by the Hop Breeding Company and the Association for the Development of Hop Agronomy is not likely clear to a brewer unfamiliar with industry politics. The ownership of the intellectual property (IP) associated with their proprietary varieties is at least one level removed from the entities selling them. That said, the ownership of the HBC, however, is not a secret.

HOP BREEDING COMPANY (HBC)

The about page of the Hop Breeding Company explains the ownership of the company, when and why it was formed. “Formed in 2003, the Hop Breeding Company, LLC (HBC) is a joint venture between John I. Haas, Inc. and Yakima Chief Ranches, L.L.C. (YCR)”[12]

The pathway HBC varieties take to reach brewers via John I. Haas is obvious. John I. Haas is part of the Barthhaas Group[13]. Their global distribution partner network, which they list on their web site is impressive[14][15]. The route HBC varieties take to reach brewers via Yakima Chief Ranches (YCR) is less direct. It involves sales via Yakima Chief Hops™ (YCH). There is a clear connection between the two if we look at their respective web sites.

YCR & YCH

The two entities have been presented as independent entities that work well together. While that may be true, there are several reasons why it is obvious. The common ownership by the Smith, Carpenter and Perrault families of both companies is the most obvious link between YCR and YCH. It is in the explanation of their origin stories on their respective web sites that the common ownership is obvious:

Yakima Chief Ranches:

“The company was started in the late 1980’s as three hop-farming families, the Carpenters, Smiths, and Perraults, came together to form a new hop production and research farm in the Yakima Valley under the name Yakima Chief Ranches. The late Charles “Chuck” Zimmerman was the initial breeding program director for Yakima Chief Ranches, with a directive to develop new hop varieties. Initial breeding results from the program were fruitful, leading to the selection and release of several new hop brands.” [18]

Yakima Chief Hops™ 1988:

“The Perrault, Smith and Carpenter families meet with Chuck Zimmerman to discuss forming a grower-owned hop company and form a strategic alliance with Pfizer.” [19]

The duplicity of the attempts to present the two entities as unique and separate is apparent in this video with Jason Perrault (a member of the Perrault family, CEO and head hop breeder of YCR)[16][17].

The companies that own the HBC, John I. Haas (JIH) and YCR, have online presences. The networks joining the two halves of the joint venture are structured differently. This makes sense since one is a hop merchant while the other is a research farm. This necessitates another layer before the hops can reach the market. Details on the Internet are vague about how the YCR-YCH half functions (Figure 9). The common ownership is clear because there are legal reporting requirements. Any voluntary information like the names of in-country distributors, is conspicuously absent. From the legally required documents, the reader can infer who possesses the greatest influence over the decision-making process. I will leave that for you to interpret.

Figure 9. HBC Ownership & Pathway to Market

Market Share

In 2020, Yakima Chief Hops™ claimed to handle 33.9% of American hops[20][21]. For this article, let’s assume John I. Haas handled a similar volume. The actual market share for merchant companies other than YCH remains a closely guarded secret. If, however, our assumption regarding JIH is accurate within +/-10%, this duopoly would be responsible for handling 60-68% of the U.S. crop in 2020 (62 – 70.2 million pounds) (28.1-31.8MT).

Why a Separate Entity?

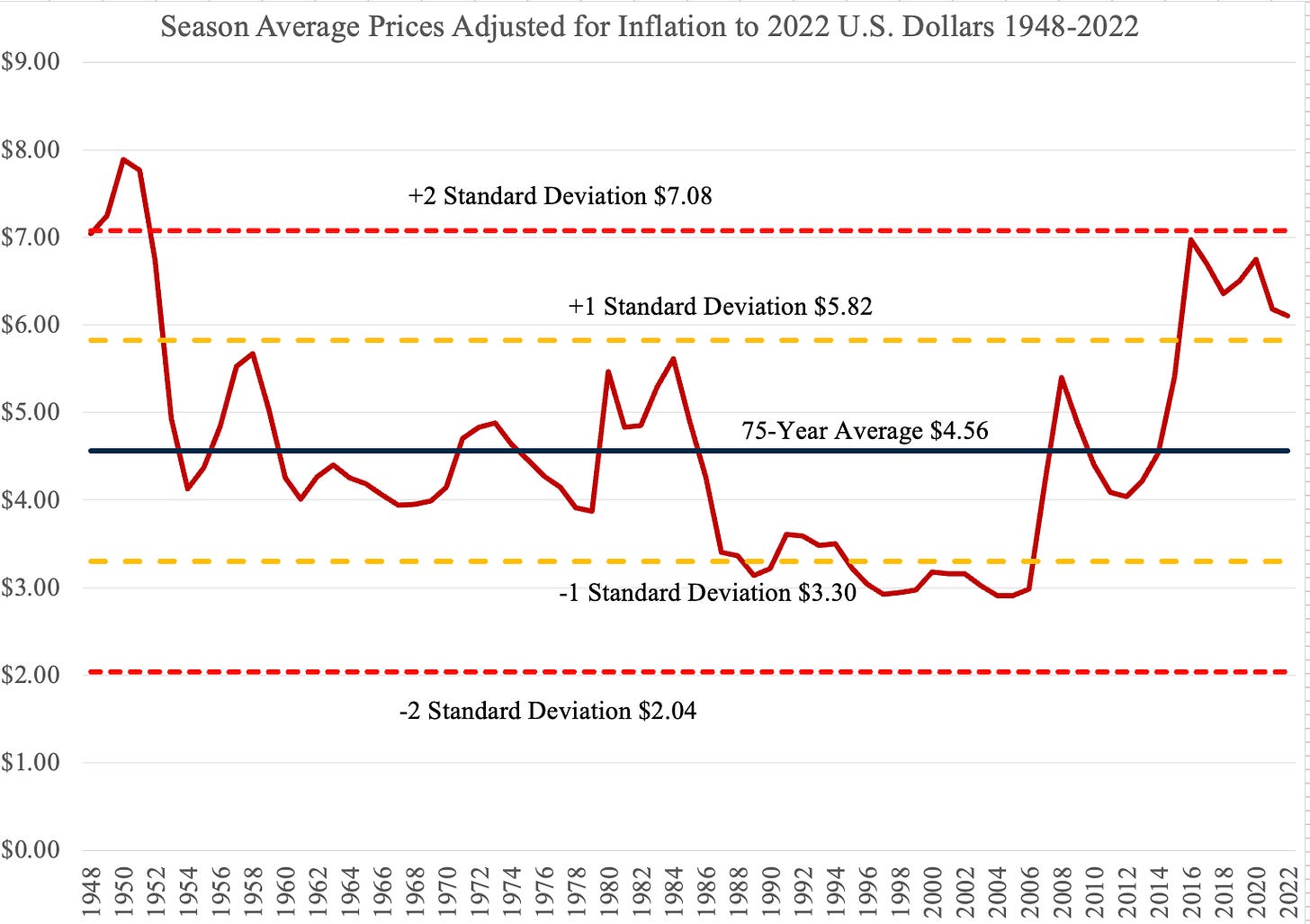

At this point, we must speculate. The only people who know the answer to that question are members of the Smith, Carpenter or Perrault families. Perhaps funding a breeding program in the 1980s was seen as a risky investment when the families decided to go the way of Monsanto and pursue developing IP and proprietary varieties. Did the Smith, Carpenter and Perrault families create YCR as a separate entity from YCH to isolate the expenses or the revenues from their YCH partners[22]? I was executive director of Hop Growers of America in 2003 when the HBC was formed[23]. Those were lean years in the industry. Season average prices were at their lowest point in a generation (Figure 10). In hindsight a good argument can be made for both.

Figure 10. U.S. Season Average Prices Adjusted for Inflation Using the Consumer Price Index to 2022 USD with Standard Deviation Demarcation and Mean. 1948-2022.

Source: USDA NASS, Bureau of Labor Statistics

This is the type of information about hops you won’t find anywhere else. If you find something you read here valuable, please consider returning the value you feel you’ve received. That’s the idea behind the value-for-value model. Money is great, but sharing this article with somebody else is another way to return value. If you have some other idea how to return some value for the value you received, that’s fine too. I would appreciate it if you could do that now.

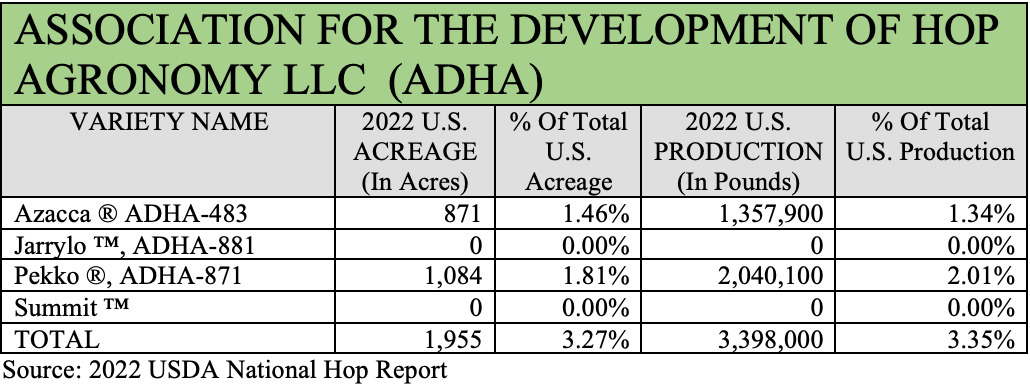

ADHA

The other company mentioned above whose ownership is not clear is the Association for the Development of Hop Agronomy, the ADHA. At the time of this writing, the ownership of this entity has never been revealed on the company’s web site (Figure 11).

Figure 11. ADHA about page.

Source: ADHA. Last viewed April 17, 2023. Available at: http://adha.us/about-adha

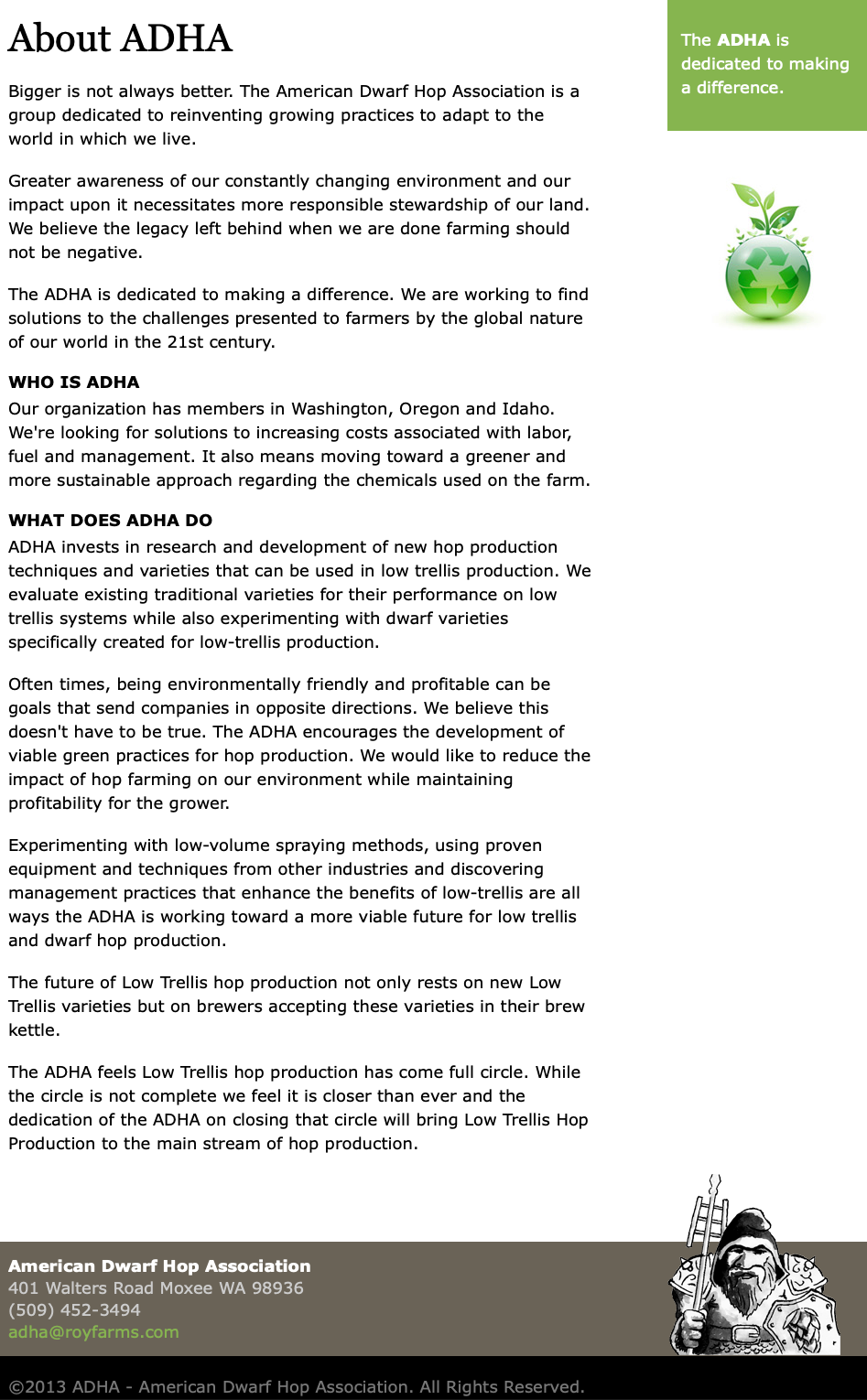

Within the hop industry, ownership of the ADHA has always been a well-known fact. When the ADHA began, the acronym stood for the American Dwarf Hop Association. The web site at that time also did not reveal who owned the company. Instead, it contained vague references to growers in Washington, Oregon and Idaho (Figure 12)[24]. If you were not aware, the Wayback Machine, allows you to search any URL to read archived versions URLs.

Figure 12. ADHA 2013 web site about page

A 2021 press release from John I. Haas (JIH) stated the ADHA was: “a partnership of by Roy Farms, Green Acre Farms and Wyckoff Farms for the progressive development of new hop varieties in the U.S.”[25] Unfortunately, the original JIH press release can no longer be found on their web site, but it remains quoted on globenewswire.com[26].

The ownership of the remaining entities involved in proprietary variety creation (i.e., Hopsteiner, CLS Farms, OSU, Jackson Hop & VGF) is straightforward and requires little to no investigation to decipher.

Transparency

In his 2020 TEDx presentation, Steve Carpenter, former CEO of Yakima Chief Hops™ discussed the company’s transparency[27]. If you’d like to skip to the 10-minute mark in the video, you’ll find the relevant section.

It makes sense why Steve would want to emphasize this about the company. Brewers believing their suppliers are transparent would create greater brand loyalty, it would build trust in the company and it would lead to stronger partnerships[28]. As a recovering hop merchant, I believe transparency does not exist in the industry except when it is convenient and/or profitable. The industry is opaque. I think it would be more accurate to label what Steve called transparency as customer feedback. We all know customer feedback leads to a better understanding of a customer’s needs and their thought processes. That is what Steve mentioned was the benefit of their program. That’s not transparency. In the system Steve described, information flows in one direction. That’s the equivalent of a two-way mirror you might see in the movies when a prisoner has been taken to the interrogation room.

An example of transparency would be to replace that two-way mirror with a pane of glass through which both sides can see. Real transparency would exchange information in both directions and benefit both parties[29]. If you’re a brewer and you’re curious whether there is transparency in the hop industry, try asking your hop supplier any of the following 11 questions:

1) What’s your profit margin on the hops you want me to buy from you?

2) What is your market share in the U.S. and abroad?

3) What chemicals were sprayed on these hops?

4) What is the true cost of production on the variety I am buying and how do you calculate that number?

5) Do you or your family members own multiple entities that perform different functions for each other that may increase the cost of my hops?

6) Do you run company expenses through multiple entities to minimize profits on any of the entities? … Does that affect the cost of the hops you want me to buy from you?

7) How do royalties affect the price of the proprietary varieties you want to sell me?

8) Who gets the royalty money?

9) How much does your hop breeding program cost to run each year?

10) What do you do with excess royalty revenue?

11) If the justification for royalties is to fund variety development programs, why are the royalties not reduced as the popularity of proprietary varieties increases?

Some of those questions are invasive. It’s understandable why companies want to limit transparency. Brewers are not always open about their inventory or the names of the suppliers from which they purchase hops either. That’s OK. Claiming to be transparent when you are not, however, is “Transparency Washing”. That’s when a company uses transparency as a buzzword to redirect attention away from more substantive and fundamental questions about the concentration of power, company policies and their actions[30]. Facebook, for example, has been accused of using transparency washing to redirect attention away from their less scrupulous practices like their involvement in the Cambridge Analytica scandal that influenced the 2016 U.S. Presidential election. I believe the same is true in the hop industry … but on a much less relevant scale.

Since 2012, the farmers and merchants involved with proprietary varieties have made fortunes that would be inconceivable to the average person. Covid exposed the weaknesses in a system of managed proprietary hop varieties. When Alex Barth announced that acreage will be severely reduced in 2023 at the Hop Growers of America convention, the belief that proprietary varieties would forever change the industry died[31].

“The truth is not always beautiful, nor beautiful words the truth.”

- Lao Tsu

IT’S GOOD TO BE KING

According to the St. Louis FED, a cartel consists of “multifirm monopolies”. That contradicts our understanding of a monopoly as a single company dominating a market. Companies involved in a cartel need only to act like a monopoly to enjoy the benefits of monopoly power.

When John D. Rockefeller built his empire, he drove competitors out of the market. He was able to control supply and distribution. He could charge high prices by restricting supply[32]. It’s not hard to imagine how these same practices might apply to proprietary hop varieties given the structure of the industry in 2023.

Cartels dissolve when the underlying economics that brought their members together change. Price wars often result[33]. As a result of the 2023 U.S. acreage reductions, some hop farms will be less efficient. That is the result of an unspoken hierarchy among hop farmers that has nothing to do with farm size or how many generations they’ve been farming. Influence is the key. Those asked to cut the most may decide it is in their best interest to act against their former partners as was the case when U.S. railroad cartels began to crumble in the 19th century[34][35].

In 2022, the USDA reported 49.75 million pounds of HBC varieties harvested. A royalty of $0.50 per pound on those varieties would have generated $22.22 million for the HBC[36]. Despite the impending acreage reductions, royalties on proprietary varieties will continue flowing to their IP owners on any acreage produced representing a continuing deadweight loss[37] to the brewing industry.

A FAILED SYSTEM

In 2003, Anheuser Busch opposed the implementation of a Federal Marketing Order claiming that such a structure would result in the formation of a cartel (Figure 13)[38].

Figure 13. Excerpt from written comments by Anheuser-Busch Companies, Inc., Vice President and Group Executive, Don Kloth.

Source: May 2019 FOIA request for 2003 Federal Hop Marketing Order documents.

In the proposed 2003 hop Federal marketing order, eight people (farmers and merchants) would have comprised a committee responsible for dictating the quantity of American hops that could be sold each year. In 2003, Anheuser-Busch Companies, Inc. Vice President, Don Kloth, testified that a central committee would not be the most efficient method to determine supply for the market. He posed the question what would happen if that central committee was incorrect (Figure 14).[39]

Figure 14. Excerpt from written comments by Anheuser-Busch Companies, Inc., Vice President and Group Executive, Don Kloth.

Source: May 2019 FOIA request for 2003 Federal Hop Marketing Order documents.

The data in this article reveals that six private companies and OSU owned the varieties responsible for 71.82% of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho hop production in 2022. Those six companies and their affiliated companies handle over two-thirds of the American crop. The similarity between the current system and the central committee proposed by the 2003 marketing order is the concentration of power into a few hands.

We now know that the current market structure, much like marketing orders from the past, failed to prevent a massive surplus. It appears the hop cycle continues on in some form. The difference this time is that while the surplus grew several individuals made millions in royalties off the trust of others who believed they would manage the market. Now that it is time to cut acreage, will the cuts be equitable? Who will pay the price for the failure to properly manage the proprietary variety supply?

“The words of their mouths are wicked and deceitful; they fail to act wisely or do good.”

- Psalms 36:3

Brewers remain silent regarding the current consolidation of hop market power. Perhaps, they, like many American hop farmers, are afraid to criticize the establishment because they fear having their access to proprietary varieties revoked. Anheuser-Busch’s position in 2003 supported farmer independence and freedom from central decisionmakers (Figure 15). I wonder what their position would be on the current situation if asked to comment.

Figure 15. Excerpt from written comments by Anheuser-Busch Companies, Inc., Vice President and Group Executive, Don Kloth.

Source: May 2019 FOIA request for 2003 Federal Hop Marketing Order documents.

Past attempts to control the hop market by concentrating power using the government failed. The current attempt to control the market by consolidating power through IP has also failed. The power to decide down which path the hop industry proceeds lies with the brewer. Farmers will produce the varieties wanted by brewers so long as they can profit.

If brewers are happy with a hop market controlled by a handful of individuals and the consequences that brings, they can continue with the status quo. If they do, they should accept inflated prices and long-term contracts that the system will continue to force upon them.

Thank you for taking the time to read this article. I appreciate the opportunity to share my thoughts on what I have learned over the years with you. If you enjoyed reading it and have not already subscribed, I would like to encourage you to do that now. If you know somebody else who might find this article useful, please consider sharing it with them too.

ONE MORE THING

If you would like to read a little more on this topic, I’ve discussed the effects proprietary varieties have had on the U.S. and world hop industry in previous articles. If you haven’t read them, please have a look at the following articles.

[1]https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Regional_Office/Northwest/includes/Publications/Hops/2022/hopsan22.pdf

[2] https://www.usahops.org/img/blog_pdf/435.pdf

[3] The figures reported were derived from the USDA NASS National Hop Report. You will notice the absence of known proprietary or experimental varieties. The USDA requires three or more producers producing a variety before it can be listed separately. For that reason, varieties that are sold commercially (both public and private) may not appear in the USDA data.

[4]https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Regional_Office/Northwest/includes/Publications/Hops/2022/hopsan22.pdf

[5] https://www.hoptalk.live/post/too-many-hops-10000-acre-cut-needed-says-barth

[6] https://www.cato.org/publications/commentary/quis-custodiet-ipsos-custodes

[7] https://www.iclr.co.uk/knowledge/glossary/quis-custodiet-ipsos-custodes/

[8] https://www.hopsteiner.com/blog/brewing-breeding/

https://clsfarms.com

https://vgfinc.com

[11] https://www.facebook.com/Jacksonhopfarms/

https://www.hopbreeding.com

[13] https://www.johnihaas.com/about-us/

[14] https://www.johnihaas.com/how-to-buy/

[15] In the U.S.: Willamette Valley Hops, Hop Head Farms, Hollingbery & Son, Inc. Hops, Yakima Valley Hops, Roy Farms, Inc. In Canada: Hops Connect Canada®, Yakima Valley Hops, Willamette Valley Hops, In Europe & Africa: Barthhaas, Barthhaas X. In Oceania: Hop Products Australia. In Mexico: Maltas E Insumos Cerveceros SA/Micervesa. In South America – East: LNF Latino Americana. In South America – West: Gecorp. In Japan: Kataoka & Ohnishi Shoji. In China: Barthhaas – Beijing, Barthhaas – Hong Kong, Shanghai Century Foods. In Vietnam: Hoang Minh Trading Import Export & Services Co., LTD.

[16] https://www.yakimachiefranches.com/about/staff/bio.html?staffid=13

[17] https://www.facebook.com/yakimachiefranches/videos/1831608463590304/

[18] https://www.yakimachiefranches.com/about/

[19] https://www.yakimachief.com/commercial/about-us/our-company

[21] There is no independent verification of the Yakima Chief Hops™ market share. The figure is based solely on the claims of persons involved with the company and may not represent actual market share.

[22] I restrict the subjects about which I write to those that can be verified by publicly available data that I can footnote. If I speculate as to the reasons for something or if I provide my analysis based on my decades of experience in the industry, I label it accordingly, so the reader knows it is only that.

https://www.hopbreeding.com

[24] https://web.archive.org/web/20130807224952/http://adha.us/about-adha

[25] https://www.globenewswire.com/en/news-release/2021/10/29/2323909/0/en/Association-for-the-Development-of-Hop-Agronomy-ADHA-Partners-with-John-I-Haas-HAAS-to-Exclusively-Market-and-Distribute-Its-Proprietary-Aroma-Hops.html

[26] https://www.johnihaas.com/news-views/haas-announces-roy-farms-as-its-newest-direct-to-customer-distribution-partner/

[28] https://www.entrepreneur.com/growing-a-business/how-transparency-in-business-leads-to-customer-growth-and/373674

[29] https://www.forbes.com/sites/mikekappel/2019/04/03/transparency-in-business-5-ways-to-build-trust/?sh=37d041ef6149

[30] https://cal.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/cal/article/view/36284/27587

[31] https://www.hoptalk.live/post/too-many-hops-10000-acre-cut-needed-says-barth

[32] https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/july-1999/cartels-breaking-up-aint-hard-to-do

[33] Journal of Economic Literature Vol. 44, No. 1 (Mar., 2006), pp. 43-95 (53 pages) Published By: American Economic Association. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30032296

[34] https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/july-1999/cartels-breaking-up-aint-hard-to-do

[35] https://mises.org/library/why-do-cartels-fall-apart

[36] I am not aware of any royalty fees charged on the CTZ varieties. To reach the $22.22 million figure, I therefore subtracted the CTZ production from HBC production and applied the $0.50 per pound royalty figure to the remainder. If you believe different calculations are necessary, or if you believe there are other varieties on which royalties are not charged, you are welcome to adjust the estimate upward or downward as necessary.

[37] https://www.investopedia.com/terms/d/deadweightloss.asp

[38] Exhibit 22 from a public hearing on a proposed marketing agreement and order for hops grown in Washington, Oregon, Idaho and California. October 15-17, 2003, in Portland OR. and October 20-24, 2003, in Yakima, WA.

[39] There were merchants at the time that agreed with Mr. Kloth. Their testimony is recorded and available.