Back in the day

To understand the development of proprietary varieties during the past 20 years, we have to travel back to the glorious 1980s. Life was simpler then, but not in the hop market. The hop market was in turmoil. This is intended to be a big picture overview of events between 1980 and 2000 that led to the idea that proprietary hop varieties would be a worthwhile venture. If reading about that sort of thing sounds less exciting than watching paint dry, or if you feel you already know all the details, you might want to skip this article.

In the years leading up to 1980, German growers had several years of short crops that brought the supply situation near a deficit. That smelled like opportunity for the Americans at the time. The Hop Administrative Committee (HAC) from the third Federal Marketing Order (1965-1986), made up primarily of farmers, voted to rapidly increase production in response. U.S. hop farmers in charge of the committee decided to capitalize on their ability to plant and harvest a crop quickly[1] to increase the market share for American hops at the expense of their German counterparts[2]. It would be years before the surplus they created could work its way through the system (Figure 1) because it came at exactly the wrong time. Dissatisfied with the marketing order since it clearly hadn't worked to combat human nature, farmers voted for the termination of the order in 1986[3].

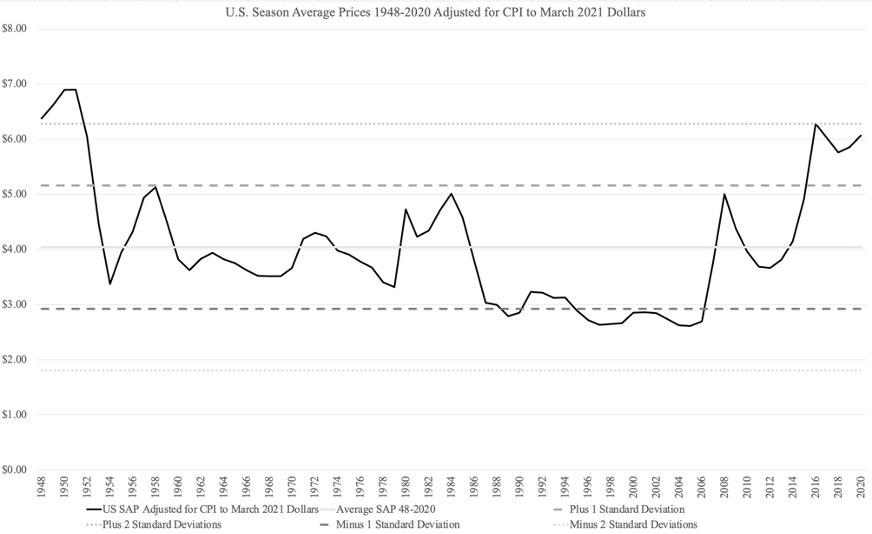

Figure 1. U.S. Season Average Prices 1948-2020 adjusted for CPI into March 2021 U.S. Dollars.

Source: USDA NASS, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistic

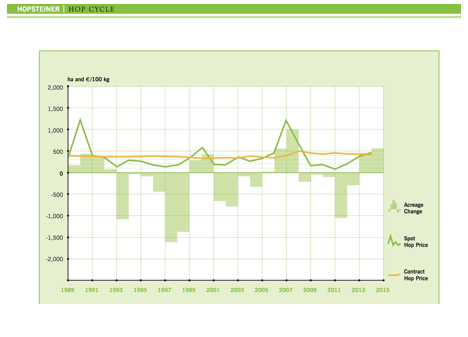

The season average price data used to create the chart in figure 1 combines spot and contracted sales on all aroma and alpha varieties. It represents an average of all reported prices. Extreme highs and lows therefore aren't represented. Spot market prices fluctuate way more than contracted prices (Figure 2). I've heard from people who were in the market at the time (I was busy riding dirt bikes, playing Dungeons and Dragons and watching MTV) that hops that were five dollars per pound on the spot market one year sold for 30 cents per pound the next.

"Don't Cross a river if it is four feet deep on average."

- Nassim Nicholas Taleb

High alpha varieties

Around that same time, the USDA released two new public varieties that were considered "high alpha", Galena (1978[4]) and Nugget (1983[5]). They yielded more hops and alpha per acre than the varieties that preceded them. In what will become obvious is typical farmer form, U.S. hop farmers did not reduced accordingly. Similarly, they didn't destroy any excess production. These are themes that still haunt the industry to this day. As a result, a surplus developed.

Figure 2: The Hopsteiner Hop Cycle

Source: 2015 HopSteiner Guidelines for Buying Hops

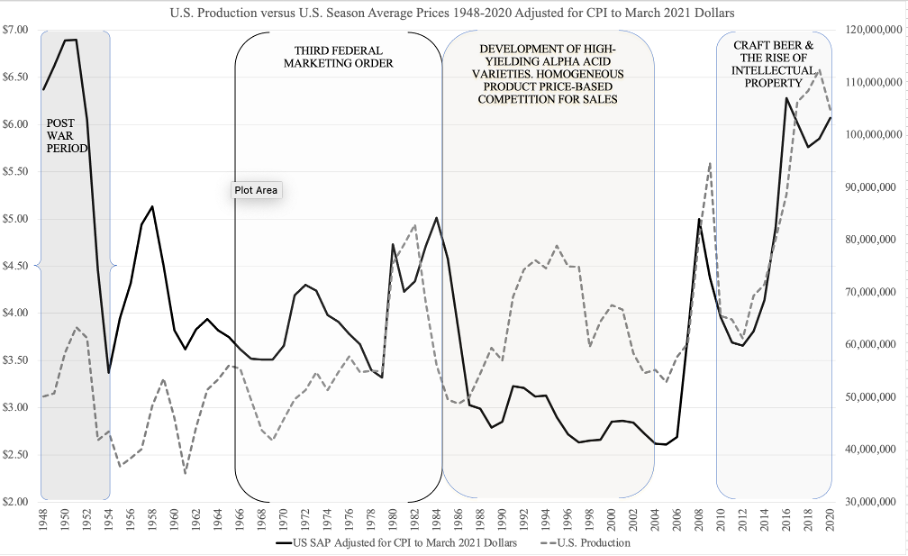

When the alpha produced by CTZ and the other similar varieties hit the market like a freight train during the late 1990's, hop farmers could produce even more hops and alpha per acre ... at least 60% more by some estimates. Again, corresponding decreases in acreage didn't occur and excess production was not destroyed (surprise surprise). As supply increased, it created more downward pressure on prices. In the early 2000's, the surplus caused several hop farmers to sell spot alpha hops for their cash costs of harvesting the crop. At the time, in closed circles, they said that price was $0.50 per pound[6]. Between 1980 and 2005, merchants developed proprietary alpha-based products that delivered greater brewing efficiency. Since these new products were based on alpha acid, a homogenous product resulting from public varieties, and because there was no longer a Federal Marketing Order in place to regulate the saleable quantity of hops, it was anything goes in the market. These products' efficiency further exaggerated the surplus by reducing demand for hops. The abysmal market that resulted lasted a quarter of a century (Figure 3).

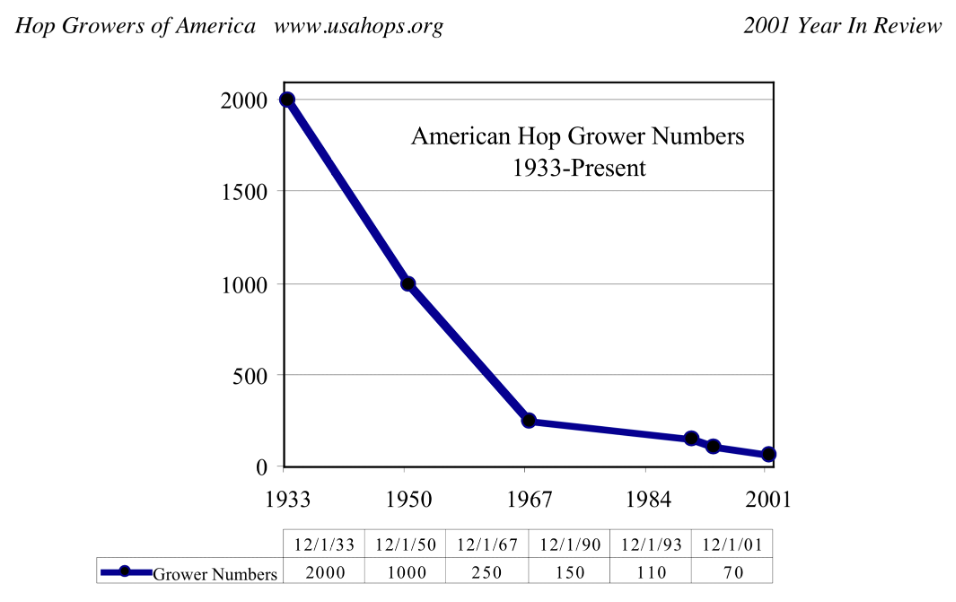

Mechanization led to greater efficiency, a necessary biproduct of chronic low prices. The 20th century increased the potential for larger farms and fewer hop farmers. As farm efficiency increased, prices unsustainable for smaller less efficient farms became the norm, which contributed to grower attrition (Figure 4). Massive corporate farms (still called family farms by the people that owned them) developed. The farmer's reluctance, or inability, to reduce or destroy production to compensate for increased efficiency guaranteed equilibrium was never be reached. This plays a role in the supply situation in 2022, and it is a theme that will resurface again in future articles.

Figure 3: U.S. Production and U.S. Season Average Prices 1948-2020 Adjusted for CPI to March 2021 Dollars.

Source: USDA NASS, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Figure 4: Number of American Hop Growers in the Pacific Northwest 1933-2001

Source: Hop Growers of America Newsletter 2001 Year in Review

Hop farmers conspiring to raise prices

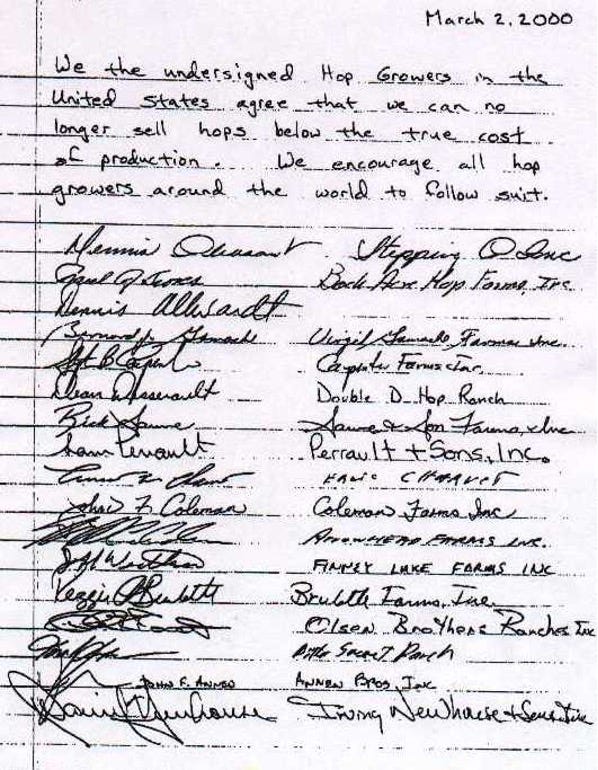

In 2000, American hop farmers tried to unite under a group they called The Hop Alliance to reduce acreage. Farmers are allowed to do that sort of thing according to the Capper-Volstead Act of 1922[7]. I'm sure neither Capper or Volstead were thinking of the hop industry where one person can own a company that develops proprietary varieties, a farm that produces hops, a processing facility to turn them into the products brewers want and a merchant company that sells and distributes them around the world. That's a tangent we'll save for another day.

The Hop Alliance was the only industry-wide attempt by hop farmers at the time to voluntarily reduce acreage. The men that ran companies that had competed against each other for decades sat side by side searching for a solution. It didn't work. Some farmers removed acreage while others, smelling opportunity, planted more.

Figure 5: The Hop Growers' Doctrine

Source: Hop Growers of America March 2000 Newsletter

One last attempt to work together to regulate

In 2003, the already weakened industry was further divided by a movement to start a fourth Federal Marketing Order. That would have set a record. No other industry had considered so many marketing orders. The push for a new marketing order failed. Don Kloth, Vice President and Group Executive, Anheuser-Busch Companies, Inc., and Chairman and CEO, Busch Agricultural Resources, Inc., was one of the many people who testified against the order. In his written testimony to the committee he began the summary of his comments by saying,

"A hop marketing order is designed to increase price

by affecting US supply by forming a cartel."[8]

Don Kloth may have been unaware that that very year the seeds of a new industry with cartel-like powers were already being planted. We can't say what Don knew or didn't know at the time. It is clear, however, he and his colleagues viewed supply controls as something potentially detrimental to the interests of his employer, the world's largest brewer at the time. He issued a public statement in writing on behalf of his employer against the structure he believed would "form a cartel". In hindsight some of the hop farmers most vocally opposed to enacting a new order were some of those who benefited from the development of proprietary varieties. Could they have foreseen where the industry was going? Although I love a good conspiracy, that’s not very likely. It was the surge in the popularity of craft beer in 2010 that led to increased demand for proprietary hop varieties. The people developing proprietary hop varieties at the time were trying to create a competitive advantage for the market in which they lived when the original crosses were made. If we’re talking about the hop world of 2003, some of those varieties may have been originally crossed as early as 1993 when craft beer was still an eclectic local phenomenon.

If you love craft beer and the image of rebellion against the macros, as many today do, you might see that as typical big brewer behavior trying to exert its power to control its poor suppliers who are powerless to defend themselves. Oligopsonies[9] do exist and the relationship between the brewing and hop industries in 2003 could have been just that. The testimony of Don Kloth alone, however, isn't proof of that. I wasn't a merchant at the time so I can't speak from first-hand knowledge how the market worked back then. In 2009, however, I was more than a little surprised when a macro brewer told me they wouldn't be needing the rest of the five-year contracts they had signed with my company (we were in the third year at the time). They offered me several million dollars-worth of European hop business if I canceled their American contracts which were worth much more. I refused because I had the contracts covered with American farmers. In the end, based on my refusal to play ball (I assume), they walked away from both their European and American contracts, went silent and lawyered up. They purchased less expensive hops on the spot market for the next few years. I didn't have the millions of Euros necessary to pursue them in court ... so ultimately, they got what they wanted.

As some craft brewers grew, they adopted some of the very traits of the very macro brewers from which they originally rebelled. I experienced this first-hand as a merchant between 2015-2017. It wasn't pretty. That's a story for another day too though. So, stay tuned, and consider subscribing if you haven't already.

I'll be publishing something around the 1st and 15th of each month so as not to fill up your inbox. If you haven't already, I hope you will consider subscribing.

These articles are free. If, however, you found some value in what you read and would like to provide some value in return, you can donate here. There’s no obligation to donate if you cannot afford it.

Cheers!

[1] In Washington and Idaho, farmers can plant a crop in the spring and harvest it in the fall. Everywhere else in the world where hops are grown the first crop cannot be harvested until the 2nd or 3rd year depending on the variety in question. This gives hop farmers in Washington and Idaho a distinct advantage over their competitors from other countries.

[2] Folwell R.J., Mittelhammer R.C., Hoff F.L., Hennessy P.K. (1985). The Federal Hop Marketing Order and Volume-Control Behavior. Agricultural Economics Research 37: 17-32.

[3] www.latimes.com-archives-la-xpm-1986-09-10-fi-13182-story.html

[4] https://learn.kegerator.com/galena-hops/

[5] https://learn.kegerator.com/nugget-hops/

[6] This information comes from personal conversations I had with the growers involved. In the interest of protecting their confidentiality since they are still growers, and given that the information was told in confidence, I will not mention the name of the growers in question.

[7] https://www.rd.usda.gov/files/cir35.pdf

[8] From the testimony of Don Kloth delivered in a public hearing on a Proposed Marketing Agreement and Order for hops grown in Washington, Oregon, Idaho and California held by the USDA in Portland, Oregon, on October 15-17, 2003, and reconvened in Yakima, Washington, on October 20-24, 2003. Exhibit 22

[9] In an oligopsony, the market is dominated by a small number of large customers. Using their large purchase volumes and the implied or inferred threat of moving those purchases to competing suppliers, customers (in this hypothetical example, macro breweries) can influence input prices and/or receive special terms. Their size and the willingness to exploit their suppliers' fear of losing their business gives them a competitive advantage not available to their smaller competitors.