Six Myths About Hops, Earth Day Sustainability, and Market Shrinkage.

MacKinnon Report April 23, 2024

In this Issue …

In this edition of the MacKinnon Report, I talk about sustainability in the hop industry and the solution to making the hop industry more environmentally friendly. See “Earth Day” below.

I expand on a LinkedIn post I made a few weeks ago in which I listed six myths about hops. So, this is six-in-one article. See “Six Myths” below.

I discussed the news from the Brewers Association about declining U.S. beer production and the impact it will have on the hop industry. See “Shrinkage” below.

I hope you’ll enjoy reading this edition of the MacKinnon Report as much as I enjoyed writing it. If you haven’t already subscribed, I hope you’ll consider it today.

EARTH DAY

In honor of Earth Day this week, I thought I’d write a bit about sustainability and hops. Sustainability is a wonderful goal. Wouldn’t the world be wonderful if we were all satisfied living a minimalist lifestyle living off the land while reusing and recycling products? Today’s sustainability movement doesn’t encourage that. It encourages us to continue our conspicuous consumption but in certain ways that are perceived to be better for the planet, but are they?

Since 2012, American merchant/farmers flexed their sustainability to portray an environmentally friendly image while at the same time doubling the natural resources they consumed. In my December 2022 article “Hops are green … But are they sustainable?”, I wrote about the environmentally friendliness of hops.

Since the industry switched to drip irrigation en masse, the methods for producing and harvesting have not changed much. Around the world, hops are dried using massive amounts of fossil fuels[1][2][3][4][5]. Hops are stored in massive cold storage warehouses year-round at temperatures near freezing[6]. According to Hop Growers of America, in 2023 alone 17,055 metric tons (37.6 million pounds) of American hops were shipped to customers around globe[7][8]. These processed can become more efficient over the past decade, but they have not changed.

To lend money, banks require borrowers meet ESG guidelines[9]. The World Economic Forum claims customers prefer to buy from companies with which their interests align[10]. Even Greenpeace says that “net zero” is a scam designed by elites for profit[11][12][13]. If you’re interested in the subject, you might find “Climate The Movie” worth watching. It was released in March and is available for free on YouTube and presents information many people may not have heard from many credible sources.

Whether it’s all a scam or not, saving the planet has created opportunities to influence customer perception[14]. Of course, the system has been abused. Companies highlighting little or no changes while touting their environmentally friendliness and sustainability is greenwashing or bluewashing[15][16]. Consumers are starting to recognize vague and exaggerated claims of sustainability for what they are[17]. Lawsuits confronting corporate greenwashing are on the rise[18][19]. In Australia, in March, Vanguard was found guilty of greenwashing[20]. Statements the company made regarding an “ethically conscious” investment fund were found to be potentially misleading to investors[21]. Investment companies are often fiduciaries, which are held to a higher standard than other companies. Shouldn’t all companies strive to be transparent and honest[22]?

Snow across parts of Europe on April 22, 2024 … Earth Day.

One problem that cannot be avoided is that every aspect of the hop business consumes significant natural resources. But some say there may be hope on the horizon. John I. Haas claims its new varieties will be more environmentally friendly[23]. Hopsteiner says the same … but about their varieties[24][25]. They make convincing arguments. Both suggest inputs like fertilizers, pesticides and water consumption relative to yield are the way to measure environmental friendliness and sustainability. Although they seem to agree on that, their analyses favored their own company’s proprietary varieties over their competitor’s[26][27]. Yakima Chief Hops™ does not seem to take this approach[28]. However, if you read the Hopwire Blog, you might be forgiven for thinking the company’s raison d'être is to save the planet[29][30][31].

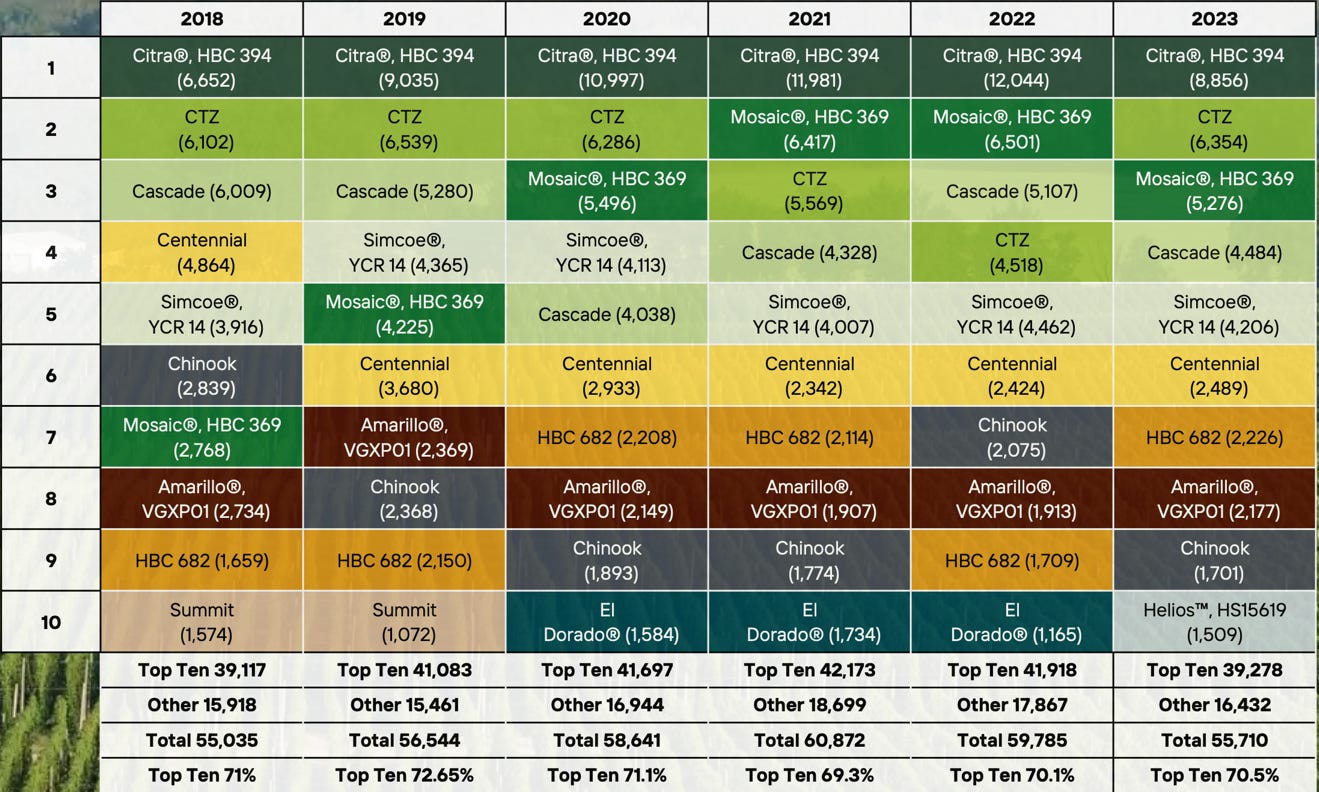

No objective way exists to determine how one variety or company might be more sustainable than another. I doubt something as simple as that is possible due to industry politics. Organizations like Hop Growers of America (HGA) or the International Hop Growers Convention (IHGC)[32], which are presumed to be neutral are controlled behind the scenes by powerful companies with financial interests in selling their own proprietary products. An objective sustainability standard would favor one variety (i.e., one company) over another. That cannot be allowed. The stakes are high. In January, Hop Growers of America published the list of the ten most widely planted varieties in the Pacific Northwest (PNW). Seven out of the ten were proprietary (Figure 1). A power hierarchy with a culture of intimidation and retribution permeates every facet of the industry. That keeps objective truths like sustainability from seeing daylight. The result is the environment is reduced to a way to sell more hops.

Figure 1. Yields of the Ten Most Widely Planted Varieties by Acreage in the U.S. 2018-2023.

Source: Hop Growers of America 2024 Statistical Report[33]

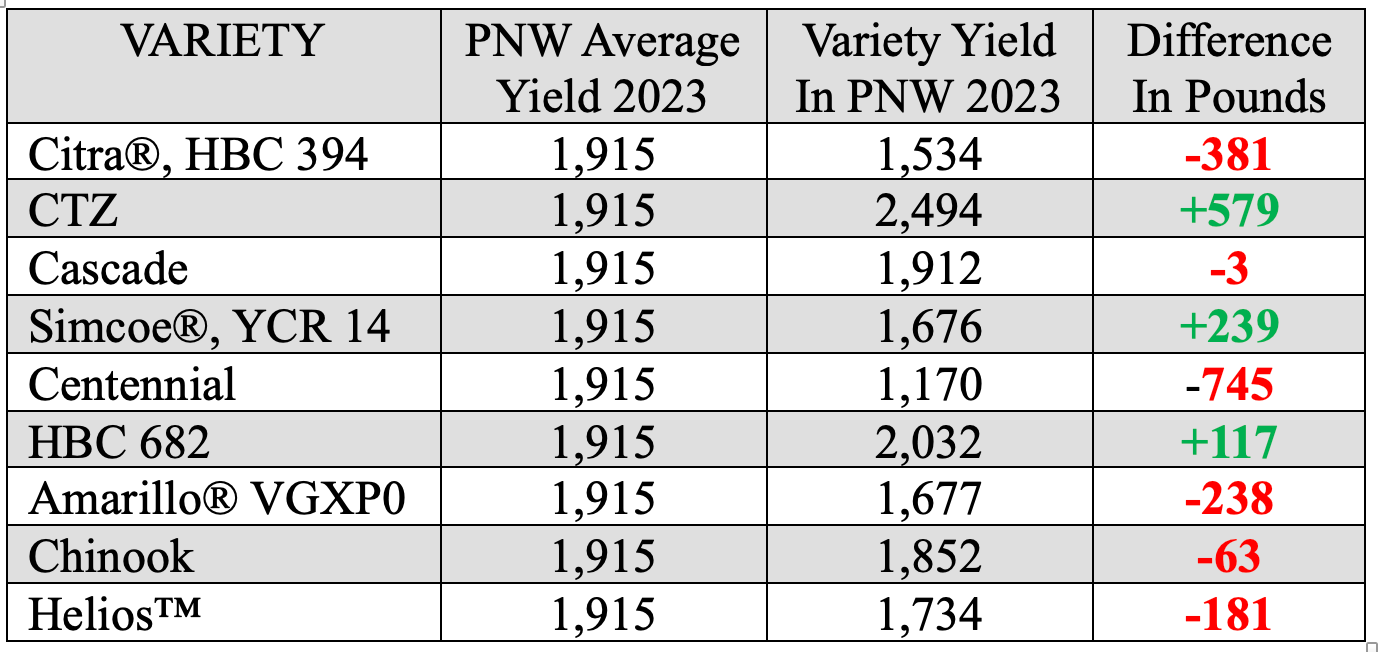

Since the big merchants agree yield is a valuable metric to analyze environmental impact, let’s explore that further. In 2023, the average yield for hops produced in the PNW was 1,915 pounds per acre (2.145 mt/ha). Seven out of the top 10 varieties had yields that were below the average (Table 1).

Table 1. Average variety yield for the 10 most widely planted hop varieties in the PNW relative to the average yield for all varieties produced in the PNW in 2023.

Source: USDA NASS 2023 National Hop Report

Sustainable Hop Solutions

If we’re honest, there is only one solution to significantly reduce the harmful impact of the hop industry on the environment … use fewer hops. There are two ways brewers can do that.

1) Breweries can use fewer hops by using more efficient brewing methods. The craft revolution was great for hop sales. The money available and the race for market share encouraged brewers to use inefficient brewing methods, like dry hopping, to get the flavors they sought. The inefficiencies of cost impact of dry hopping are explained by brewer and podcaster Chris Lewington in this LinkedIn post.

2) Breweries can incorporate extracts or downstream products into the mix. If they figure out the products they need to get the flavors they want, downstream products would create less of an environment impact while producing the same amount of beer. Companies like Totally Natural Solutions, HopXL, or Abstrax exist for that purpose.

There are several other companies in the downstream product space too. They’re not hard to find. Big merchants also offer downstream products that address this issue[34][35][36].

SHRINKAGE

According to the Brewers Association, the US craft industry contracted 1% in 2023 and the total beer market shrunk by 5.1%[37][38]. Competition has intensified[39]. Fortunately, the selection of high quality Non Alcoholic (NA) beers has grown. That will keep consumers concerned about the negative health effects associated with alcohol from leaving the market.

As the only significant source of money for the hop industry, that means a shrinking hop market. Today’s market has a massive surplus[40]. There are rising costs of production due to inflation[41]. There is the controlled reduction of proprietary variety acreage.[42] Finally, there are large hop farms with access to resources that do not want to become small hop farms. The conditions are ripe for the industry to implode due to infighting. It represents a bonanza of opportunity for brewers once they work through existing inventories.

SUBSCRIBE

SHARE

SIX MYTHS

This article comes from a LinkedIn post I made earlier in April (see below)

Myth #1: The hops you select in Yakima are the hops you get.

Brewers believe when they visit their favorite merchant in Yakima during harvest and select hops that they get the hops they selected. That’s not always true. The idea that the hops you will get are exactly like the hops you selected in Yakima. It depends on a couple things.

It depends on the quantity of hops you’re buying.

a. Big breweries spend more money. Merchants ensure they get the best product.

b. If you’re not buying a large quantity of hops, let’s say 30,000 pounds (13.6 mt), the hops you sniffed could be mixed with hops from other lots during the pelleting process. The big merchants process a lot of hops in a short amount of time. The mixers can be large. This is to create large uniform batches of hops instead of lots with different characteristics[43]. This is why there are group and solo selections[44].

Regardless of the quantity, a sample from one or two bales does not represent an entire lot of hops[45].

Do the characteristics of the hops you smelled in Yakima make their way into the beer[46]? That’s a complicated process, but merchants do their best to facilitate your recollection of what a brewer experienced during a previous selection.

How many hop samples can you sniff before your nose can’t smell anything anymore? That’s called olfactory fatigue or nose blindness[47][48][49]. It can happen in minutes and there’s no way to prevent it[50]. I doubt merchants will tell you about nose blindness during the sampling process. Good news though … Drinking a moderate amount of beer while selecting hops enhances the olfactory senses[51].

If you’re not buying multiple pallets of each variety you need, manage your expectations regarding selection. Realize, that for most brewers, selection is a promotional/marketing expense for the merchant. That said, it’s a fun experience and a good chance to learn about hops and meet the people involved in the industry[52]. The scale and pace of the American hop harvest is a unique and impressive experience.

If you consider it entertainment, you won’t be disappointed. Brewers should make the trip while the industry is still at its peak. The industry will be changing soon.

QUESTION EVERYTHING:

If you’re a brewer showing up in Yakima for selection, what are you selecting? Where you are in the pecking order? If 1,000 brewers selected hops before you, are you getting the best hops … or just the best from what’s left? How do you know when to visit to get the best selection? Does timing matter? Is the amount you spend important? Does your relationship with the seller make a difference? Is it worth the expense?

Myth #2: The U.S. has an effective public breeding program.

American public breeding programs produce varieties, which during any other time in hop history would have been well received. The plant breeders at work have the technical skills to create useful varieties with desirable flavors. In that way, it is more effective than ever. The quality of the varieties they produce is not in question. The issue is who will sell those varieties?

“If a tree falls in a forest, and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?”

- Charles Riborg Mann, George Ransom Twiss, "Physics" (1910), p. 235.[53]

In 2017, the Brewers Association (BA) gave the U.S. hop industry $1 million in 2017 to “create …”[54]. This was a nice symbolic move, but naïve on their part. It demonstrated their complete lack of understanding how hops are sold. It reminded me of the 1989 movie Field of Dreams when a spooky voice says to Kevin Costner, “if you build it, he will come” meaning he should build a baseball diamond in the middle of his corn field.

Of course, that’s Hollywood so when he built the field the players came. One of the players was his father. They play catch at the end of the movie in a scene that will make you cry (watch it at your own risk)[55].

The idea that new public hop varieties will succeed because somebody created them is a dream. Again … follow the money. Today, public varieties compete not on their merits alone, but against proprietary varieties that generate royalties that create a financial buffer and a competitive advantage for their owners. Put differently, some merchants have fewer financial incentives to sell public varieties.

Farmers who receive those royalties from their proprietary varieties will outlast the ones that simply grow them. The more popular the proprietary variety … the bigger the buffer and the competitive advantage. According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, royalties are a deadweight loss causing the cost (of hop varieties in this case) to exceed their real value[56][57]. Royalties on hop varieties, therefore, are a sign of the market’s inefficiency and irrationality.

Presumably, merchants will claim they act fairly because they offer public varieties for sale and it’s up to the brewer which hops he wants. Brewers have no way to navigate the minefield of half-truths merchants and farmers tell them, of which this is one. In truth, there is no merchant who promotes public varieties when they can promote proprietary varieties they own. If you don’t believe that, try this simple experiment, but prepare to be shocked. Visit the Instagram accounts for Yakima Chief Hops™, John I. Haas® and Hopsteiner. Looks at their posts for the last few months. See how many times they promoted proprietary versus public products. You’ll notice a strong bias in favor of proprietary products. Industry groups would be the ones to do promote public varieties, but they were coopted by powerful forces working behind the scenes to achieve their goals long ago.

“A half-truth is a whole lie.”

- Yiddish Proverb[58]

A similar thing happens to breweries with distributors under the three-tier system. The three-tier system favors large breweries[59]. A small brewery may list their beer with a distributor. That does not mean that the distributor tries to sell their beers. It means it’s available on their list of beers they can provide. Independent craft brewers must often market their product to customers themselves.

Their strategy takes advantage of 10 powerful cognitive biases marketers use to increase sales[60][61][62].

Myth #3: It’s best to buy the freshest hops because older hops are lower quality.

This is the perception. This doesn’t apply to crop year 2022 hops. Three- or four-year-old pellets can deliver the same performance as fresh crop at half the price in a surplus year like 2024. Extracts have an even longer shelf life.

PRO TIP:

In general, fresh hops are better than older. When that change becomes noticeable, however, is the question. For craft brewers who don’t already know, it takes a few years before you approach that line. If hops have been pelleted and stored according to industry standards, there won’t be any significant degradation for three or four years … at least. Due to the misperception by the brewing industry, older hops are sold at a discount. Their higher return on investment makes them the best deal in the industry. That does not mean that crops five years or older are worthless either. More on that later.

Most brewers have heard of the Hop Storage Index (HSI). The common belief is that anything under 0.3 is good. As hops age the HSI increases with time. HSI has an inverse relationship with the presence of useful compounds. The higher the number goes (e.g., 0.4 … 0.9) the lower the quality of the hops are perceived to be[63]. I believe that’s the origin of the myth that older hops are lower quality. That could turn into “old = bad”. The problem with HSI is that it’s a simplistic way to measure hop quality.

Here are a few things wrong with the idea that older hops are of lower quality. This list is not intended to be an exhaustive list:

Weather – Rainfall, heat, drought and pests can affect, alpha acid content[64], essential oil production and yield. The previous year’s crop produced under better circumstances can offer a higher quality than the current crop. If a variety is picked late, that affects the HSI score.

Proper Storage - Proper cold storage of hop products slows the degradation process[65][66]. Today, cold storage is the norm[67][68]. How quickly hops will degrade depends on the temperature at which they are stored[69].

Terroir – A variety produced in a different region can affect flavor and performance. If the expectation is for a Washington Cascade flavor, but the Cascades were grown in Germany, the hops will not deliver the flavor of a Washington Cascade[70]. The same is true between hop production in different U.S. States.

Variety difference - Different varieties degrade at different rates. Nugget variety alpha acid remains stable after harvest for months. The CTZ variety, on the other hand, must be processed immediately.

Plant Age – Young hop plants have more vigor than an older plant. Their productive life differs by variety.

Pellet Age - Hops pellets processed three to five years ago still contain most of their original characteristics … if they have been packaged and stored properly. Part of the problem with the current pesticide regulation changes in the EU is that many breweries still have and had planned to use hops from 2020, 2021 and 2022, which will soon be illegal to use. If hop quality is not preserved, the industry is going to the great expense of flushing mylar foils with nitrogen/CO2 and storing product at near freezing temperatures for no reason.

Picking Window – The harvest date affects quality. Every hop variety has an ideal picking window. The window for a field depends on that field’s location and many of the variables included above. If a variety is picked outside that window, the characteristics of those hops change[71]. Harvesting a variety late can have a positive effect on essential oil content in some varieties[72]. According to the Brewers Supply Group (BSG), when Amarillo® VGXP001 is harvested late it exhibits onion or garlic flavors[73]. Eric Desmarais from CLS farms discussed the changes he noticed with El Dorado™ brand hops during the 2023 crop on the Drink Beer, Think Beer podcast. You can listen to that at the link below.

I could go on. The point is that there are so many reasons that older hops are not inferior products. Brewers who already understand this should share this article with their brewer friends who don’t so they can save a little money by buying older hops.

RELATED:

A new company, HopXL, claims that older hops are no longer useless and HSI can be ignored if the hops are transformed into one of their products. They are exhibiting at the CBC this year for the first time. I have been invited to visit their facilities in San Diego and hope to learn more about their products in the coming months.

Myth #4: Without forward contracts, farmers can’t produce hops.

Contracts are a trojan horse used to funnel hundreds of millions of dollars into the industry. I’ve written about that before in my August 2022 article, The “Con in Hop Contracts”. It is more accurate to say that without contracts farmers won’t overproduce hops. Contracts are marketed as a way for farmers to know what to produce. For that to work, the brewers signing the contracts need to know what they need.

When the industry was dominated by 50 macro breweries who understood the market, supply was easier to manage. Contracts got out of control when the U.S. craft industry went from 900 to 9,000 breweries and the system didn’t change. Why would it change. Again, follow the money! Imagine a growing and changing market made up of thousands of inexperienced brewers none of whom have hop purchasing experience. Now, tell them they must forecast the demand for multiple hop varieties five years in advance. The system was designed to extract maximum value from the brewing industry.

DURESS OR UNDUE INFLUENCE:

Were five-year contracts forced upon small craft breweries signed under economic duress? Did sellers with exclusive access to proprietary varieties exercise undue influence to force long-term contracts upon craft brewers. If so, either could invalidate the contracts. You can read more about economic duress and undue influence here.

The problem is for every 100 bales of hops contracted most farmers plan to produce between 103-105 bales to account for the uncertainty inherent in agriculture. When contracts are plentiful and prices are high, farmers want to deliver in full to get every dollar. They overproduce as a result. When contracts are scarce and prices are low, they must collect every dollar possible. Again, they overproduce. Because hop farmers are good at what they do, seldom do yields dip below average[74]. There is never an incentive for farmers to underproduce. Those extra hops are never plowed back into the field once they’re baled until years later when it’s clear they won’t sell. That is why, until now, there has never been a hop shortage.

This brings up one of the more challenging situations of hop production. The only way to know how many hops a farmer produced is because he tells you.

FUN FACT:

In 2007-08, one American hop cooperative that no longer exists found itself in a difficult situation. Prior to the 2007 hop harvest, the farmer owners committed their hops to the cooperative at prices that were normal for the time. As 2007 progressed and prices soared, those farmers started noticing. The prices at which they had promised to deliver their hops seemed ridiculous. Market prices were 20 times higher. They began to short their commitments to their own cooperative and began selling outside of the cooperative. The reasons … “the crop was coming in light” … “yields were down”. This was to their own company, which threatened to sue them over the short deliveries. This is the sort of thing attributed to farmers in Central and Eastern Europe. The same thing happened in Central and Eastern Europe in 2007 enraging at least one German hop merchant. This is the reason hop cooperatives eventually fail. They are a wonderful way to collect money when prices are good. They are a guaranteed sales outlet when prices are bad. They do not handle transitions well. Proprietary varieties change the dynamics. Whether the coops of today survive remains to be seen. Will the independent farmers who remain invest millions and expanding acreage of proprietary varieties they do not own when demand increases in the future? European hop farmers have a system to document production on every farm dating back to when subsidies were linked to production unlike they are today[75].

Myth #5: Paying the fair price recommended by the US industry helps support farmers.

Of course making more money is always good. In that way this myth is true. Voluntarily paying much more than a farmer needs to make a reasonable profit support them more than simply paying a reasonable price.

“Pigs get fat, hogs get slaughtered.”

- Unknown

Brewers that pay premium prices supports hop production. They could be saving money, or getting more hops and still offering their favorite farmers a reasonable profit in the process.

Caveat Emptor!

FUN FACT:

The purchasing agent for a very successful brewery told me, “I don’t mind if we’re paying too much for our hops. We can’t risk ruining our relationships with the merchants we’ve worked so hard to develop.” I am sure his boss, the owner of the successful brewery, would not feel the same. Even if he did, I’m sure he would appreciate paying extra for his hops on his own accord rather than being lied to. I haven’t mentioned it to him … yet.

The reason I place this in the myth category is because American hop farmers inflate the alleged costs of hop production far beyond their actual costs. The implication is that hops cost much more than they do to produce so they need more to break even. The WSU Cost of Hop Production Survey (the “WSU survey”) claimed hops cost $13,588.66 per acre ($33,563.99 per hectare) in 2020. Accounting for the rise in CPI inflation, that number would be $16,399.15 in 2024[76][77]. Using the five-year average yield for the Pacific Northwest (PNW) states of Washington, Oregon and Idaho was 1,915 pounds per acre[78] (2.145 mt/ha), American hops will cost $8.56 per pound ($18.88 per kg.) to produce. As farmers there continue to produce over the next year or two as prices fall, these numbers will be revealed for the farce they are.

If you’re interested in exactly how the WSU cost of Hop Production Surveys have been manipulated, please read my September 3, 2022 article “Are you Overpaying for American Hops?”, or my October 15, 2022 article entitled “How Much Do U.S. Hops Really Cost?”.

The poor farmer stereotype is deeply rooted in American culture from the mid-20th century when every farmer worked his land. There are still a handful of American hop farmers who do, but that is not the norm. The industry manipulates the numbers to anchor price negotiations higher than they would otherwise be. It’s a brilliant strategy. Breweries who don’t know what they don’t know believe what they are told. Earlier this year, I spoke with one such brewer purchasing agent. He worked at one of the ten largest craft breweries and reads these articles. He was confident he knew the true cost of hop production. When I asked how he knew, he cited the WSU survey. He should know better. I have found that most craft brewers are so busy trying to run their breweries and save money that they can’t or don’t invest the time necessary to understand the markets for their ingredients.

Myth #6: Hop Growers of America equally represents all American hop farmers.

The organization, like many of the organizations in the industry, have been hijacked. I visited the Hop Growers of America (HGA) booth when I last attended the Brau. They had samples of varieties available. Most of the hops produced in the U.S. today are proprietary. That was reflected in the varieties available for sampling. The varieties produced on half the U.S. acreage are owned by one company, the Hop Breeding Company (HBC).

American farmers who do not own the HBC or the companies that distribute their varieties, could argue against paying the state assessment funds they are forced to pay, which create a disproportionate advantage for their competitors. Over the years, farmers from several industries have challenged assessments, which were found to be unconstitutional for infringing on their constitutional first amendment rights [79][80][81]. Perhaps one of those cases can be used as precedent for what is happening in the U.S. hop industry today.

[1] https://piet.ucdavis.edu/sites/g/files/dgvnsk8286/files/inline-files/2019%20-%20RuhstallerHopKiln%20-%20FinalPresentation.pdf

[2] https://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/downloads/kw52jg829

[3]https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263817940_Optimization_of_the_Hop_Kilning_Process_to_Improve_Energy_Effi_ciency_and_Recover_Hop_Oils

[4] https://www.canr.msu.edu/uploads/234/78941/Hop_Track_-_German_Hop_Drying_Technologies_-_Florian_Weingart.pdf

[5] The 2020 WSU Cost of production survey neglects to mention the usage of fossil fuels in the drying process. They simply list a dollar value for the fuel used without specifying the amount of BTUs or liters of LNG or Propane involved. In checking for this, I have likely stumbled across another way the WSU budget is misleading and inaccurate. The data cannot be checked. We are to accept that the average 600-acre farm used $150,000 worth of fuel of some sort to dry hops. At what price was the natural gas purchased? Were forward contracts used? How can inflation be claimed if there is no baseline against which to compare it? This, in my opinion, is another example of the deception employed by the hop industry against the brewing industry. You can view the omission for yourself on page 4 of the document at the following link: https://rex.libraries.wsu.edu/esploro/outputs/99900670220101842#file-0

[6] https://hollingberyandson.com/facilities

[7] https://www.usahops.org/img/blog_pdf/474.pdf

[8] At 19 metric tons per 40-foot container, that’s 897 containers of hops that traveling overseas in 2023.

[9] https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/tech-forward/esg-data-governance-a-growing-imperative-for-banks

[10] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/12/people-prefer-brands-with-aligned-corporate-purpose-and-values/

[11] https://www.greenpeace.org/eastasia/blog/7910/shells-scandal-in-china-highlights-the-greenwashing-and-climate-risks-of-carbon-offset-credits/

[12] https://hbr.org/2022/04/yes-investing-in-esg-pays-off

[13] https://www.greenpeace.org/international/story/54079/great-carbon-capture-scam/

[14] https://www.forbes.com/sites/timothyjmcclimon/2022/10/03/bluewashing-joins-greenwashing-as-the-new-corporate-whitewashing/?sh=2f6390c3660c

[15] https://www.linkedin.com/posts/ych_happy-earth-day-friends-we-are-activity-7188193622343725057-5I3C?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop

[16] https://sustainablereview.com/see-through-green-how-to-identify-greenwashing/

[17] https://news.bloomberglaw.com/bloomberg-law-analysis/analysis-green-product-claims-face-growing-consumer-scrutiny

[18] https://news.bloomberglaw.com/esg/100-sustainable-claims-pose-mounting-legal-risk-for-companies

[19] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/apr/05/letitia-james-jbs-meat-lawsuit-greenwashing

[20] https://www.afr.com/companies/financial-services/vanguard-guilty-of-greenwashing-in-asic-s-first-major-court-win-20240327-p5ffp1

[21] https://www.gtlaw.com.au/knowledge/asics-first-greenwashing-win-federal-court

[22] https://www.forbes.com/advisor/investing/financial-advisor/what-is-fiduciary-duty/

[23] https://www.johnihaas.com/news-views/new-data-shows-incredible-sustainability-of-hbc-experimental-varieties-versus-classic-craft-hops/

[24] https://www.hopsteiner.com/blog/hop-varieties-with-reduced-carbon-footprint/

[25] https://brauwelt.com/en/news/hopsteiner/644506-environmental-impact-of-hop-varieties

[26] https://www.hopsteiner.com/blog/hop-varieties-with-reduced-carbon-footprint/

[27] https://www.johnihaas.com/news-views/new-data-shows-incredible-sustainability-of-hbc-experimental-varieties-versus-classic-craft-hops/

[28] Or at least I have not found it yet.

[29] https://www.yakimachief.com/commercial/hop-wire/climate-change

[30] https://www.yakimachief.com/commercial/hop-wire/impact-focus-carbon-reduction-blog#:~:text=Invest%20in%20research%20and%20development,greenhouse%20gas%20emissions%20by%2056%25.

[31] https://www.yakimachief.com/commercial/hop-wire/earth-day-2024

[32] https://www.ihgc.org/members/

[33] https://www.usahops.org/img/blog_pdf/474.pdf

[34] https://www.yakimachief.com/media/wysiwyg/Approved_Distributor_Guide_-_Revised_2.15.22.pdf

[35] https://www.hopsteiner.com/blog/innovations-for-brewing-and-beyond/

[36] https://www.johnihaas.com/news-views/the-future-of-dry-hopping-is-liquid/

[37] https://www.brewersassociation.org/association-news/brewers-association-releases-annual-craft-brewing-industry-production-report-and-top-50-producing-craft-brewing-companies-for-2023/

[38] https://www.probrewer.com/beverage-industry-news/business-of-beer/ba-releases-craft-beer-production-numbers-for-2023-production-down-1/

[39] https://www.brewersassociation.org/press-releases/the-2023-year-in-beer/

[40] https://brewingindustryguide.com/infographic-hops-pullback/

[41] https://www.agriculture.senate.gov/newsroom/minority-blog/usda-says-high-farm-production-costs-not-easing-in-2024#

[42] https://brewingindustryguide.com/the-next-hop-market-correction/

[43] A merchant will always buy an aroma variety, for example Slovenian Aurora, with above average alpha acid (e.g., 10-12%) to blend with Auroras from the same crop year with below average alpha (e.g. 5-7% alpha). This creates a more uniform and consistent product of 9-10% alpha Auroras. If a merchant doesn’t do this, he is left with lots of substandard product once his premium product is sold.

[44] https://www.morebeer.com/articles/Hop_Selection

[45] The quality within a lot of hops can vary from bale to bale. Moisture when bales are received represents how variable baled hops can be. It’s necessary to probe some bales in more than one place (center, top and bottom) to get an accurate moisture reading.

[46] https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/demystifying-art-hop-selection-insiders-perspective-from-thomson/

[47] https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/olfactory-fatigue

[48] https://www.healthline.com/health/nose-blindness#how-it-happens

[49] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3989720/

[50] https://www.libsaromatherapy.co.uk/post/is-nose-blindness-really-a-thing

[51] https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn25935-alcohol-improves-your-sense-of-smell-in-moderation/#:~:text=How%20do%20you%20smell%20after,sense%20of%20smell%20through%20practice.

[52] https://www.brewersassociation.org/brewing-industry-updates/hop-selection-guidelines-for-brewers/

[53] https://en-academic.com/dic.nsf/enwiki/3748347

[54] https://www.beerpulse.com/2017/11/brewers-association-funds-public-hop-breeding-program-through-usda-agreement-5435/

[56] https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w13141/w13141.pdf

[57] https://www.investopedia.com/terms/d/deadweightloss.asp

[58] https://www.forbes.com/quotes/10399/

[59] https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1211&context=wmblr

[60] https://www.josiahroche.co/blog/13-dangerously-powerful-marketing-biases/

[61] https://www.historytoday.com/miscellanies/original-influencer

[62] https://www.britannica.com/biography/Edward-Bernays

[63] https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/understanding-the-importance-of-the-hop-storage-index#:~:text=According%20to%20Van%20Holle%20(2017,indication%20of%20good%20quality%20hops.&text=Because%20harvest%20timing%2C%20temperature%2C%20oxygen,packaging%2C%20and%20storage%20is%20imperative.

[64] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338729879_Influence_of_weather_conditions_irrigation_and_plant_age_on_yield_and_alpha-acids_content_of_Czech_hop_Humulus_lupulus_L_cultivars

[65] https://www.uvm.edu/sites/default/files/Northwest-Crops-and-Soils-Program/2014-ResearchReports/Hop_Storage_Report_Jfinal.pdf

[66] https://www.infona.pl/resource/bwmeta1.element.ID-2e0e115a-556f-4576-a2bb-e7ae343d4603/content/partDownload/content/full-text/bd41fd53-dc57-4cd9-bd33-18522f59b4fa

[67] https://americanhopmuseum.org/hop-seasons

[68] https://brauwelt.com/en/sponsored-news/hopsteiner/628306-new-cold-storage-for-leaf-hops

[69] https://www.geterbrewed.com/blog/2019/03/24/how-long-do-hops-last/

[70] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/jib.648

[71] https://allaboutbeer.com/how-the-hop-harvest-window-impacts-aroma/

[72]https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314517898_Influence_of_Picking_Date_on_the_Initial_Hop_Storage_Index_of_Freshly_Harvested_Hops

[73] https://bsgcraftbrewing.com/hops-american-hops-amarillo/

[74] Lower five-year average yields are usually the result of one very bad year that drag the rest of the year’s average downward.

[75] https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/common-agricultural-policy/cap-overview/cap-glance_en#:~:text=The%20CAP%20provides%20income%20support,animal%20health%20and%20welfare%20standards.&text=The%20CAP%20shifts%20from%20market%20support%20to%20producer%20support.

[76] A more accurate way to measure in the increased costs would be to measure the individual components like natural gas, labor and other variables that are not included in the CPI figure. This is not difficult, but for the sake of brevity I used the CPI figure, which offered a similar number.

https://www.usinflationcalculator.com

[78] https://www.usahops.org/enthusiasts/stats.html

[79] https://firstamendment.mtsu.edu/article/united-states-v-united-foods-inc/

[80] https://www.theledger.com/story/news/2003/04/17/apple-commission-shutting-down/26047859007/

[81] https://caselaw.findlaw.com/court/ca-court-of-appeal/1757992.html