Did you Get the Hops You Paid For?

All hops are equal, but some hops are more equal than others.

If you believe brewing is an art, you talk about it differently than somebody focused on the science. Regardless which camp you’re in, hops are one way for terpenes like myrcene, linalool and humulene that affect flavor to get into a beer[1].

The Hop Storage Index (HSI) represents the “freshness” of the product[2]. Alpha doesn’t degrade as quickly in hops stored under the proper conditions. If you’re interested in learning more about HSI, here’s an article that’s explains everything in layman’s terms. Here is another that is a little more technical.

HSI has nothing to do with oils other than alpha and beta acids. That’s probably because until about 2010 most brewers focused on alpha acids. Oils degrade over time too though when not stored under the proper conditions. But what’s the starting point? Two subjects seldom discussed are the variability across different lots of a variety and the purity of the variety integrity in the field. Those are topics worth exploring.

Compound Interest

The oils in a variety differ each year. That depends on things like weather, water, pests, disease and their ripeness when harvested[3]. Within any given year, oil content differs from field to field on the same farm due to terroir, cultural practices and geographical differences. Every variety has a range of possible oil compositions. Yakima Chief does a great job of representing this on their variety information sheets[4].

With so much variability, how can a brewer know what he is getting when ordering his favorite variety? Well, they can ask. During my previous life as a hop merchant, this didn’t happen very often. Once, a Korean brewer asked for the linalool content of the Cascades they were buying. It was a reasonable request. We tested them.

Some brewers are concerned that climate change will affect the flavors in their beer[5]. With so much oil content variation within what is considered a variety, they would be wise to focus on more immediate threats to their beer flavor. To illustrate the variation possible … Imagine you’re shooting arrows at the target below[6]. The smallest circle in the yellow area represents the ideal oil composition of a brewer’s favorite variety. That might represent what the brewer thinks he’s buying. There is a lot of variability within what is considered a variety. In fact, anything on the paper target might qualify depending on the circumstances.

Most brewers are familiar with Cascade and Centennial. Let’s look at those two varieties to see how different they can be. As mentioned above, Yakima Chief does a great job presenting the possible ranges for the different compounds contained in each variety so we will use their variety sheets for our comparison[7][8].

Looking at possible ranges for the oils present in Cascade and Centennial some similarities emerge. The ranges for most of the oils from one variety are included in the ranges of the other. Both varieties can contain identical quantities of alpha acids, total oils, B-pinene, myrcene, linalool, caryophyllene, humulene, and “other”. The differences between the two according to the sheets above are beta acids, farnesene and geraniol. Similarities between varieties is not limited to Cascade and Centennial. That’s why brewers can find substitutes when the one they want isn’t available[9].

There are, of course, varieties whose oil profiles don’t resemble one another. It does not seem that Columbus would make a good substitute for Willamette … but I know of a brewery that did that. They did it over several years. Their customers never noticed. They saved money and standardized their recipe in the process.

The Art

That reminds me of something a long-time brewer once told me (I’ve shared this before, but it is profound and worth repeating). He said he could make any beer using five varieties. One of those varieties, or a combination of two or more of them could produce any flavor he needed. Based on his opinion and discussions I’ve had with other brewers, that seems to be true. If that is the case, there must be another reason for the popularity of new proprietary varieties.

Magenta, yellow and cyan are primary colors[10]. From mixtures of these three colors and the secondary and tertiary colors created from them, an artist who mixes his own paint can create over 10 million shades of color that are perceptible to the normal human eye[11]. The creation of shades of color are limited by the ability to sense them … not by the ability to create them. Contrast that with our sense of taste. According to this Harvard school of public health article, there are five well-recognized tastes, sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami (a savory, meaty taste). There is also growing acceptance of fat as a sixth basic taste[12]. Sensing flavor is a combination of our sense of taste, smell and touch[13]. The sense of smell is very sensitive. Brewers make their pilgrimage to Yakima for hop selection each year because they believe they can sense the aromas of certain volatile compounds. In fact, most of us can sense differences at one part per trillion[14]. So, the bar is higher, but the same principle that applies to color applies to flavor in that they are limited by the ability to sense them … not by the ability to create them.

Questions to Consider

“How do you know the aromas you smelled in the brewers cut you selected during harvest will be in the pellets you buy?”

“The brewery that goes first during selection gets the greatest potential selection from which to choose. Do the rest get their leftovers?”

“Will the lot of hops you selected be pelleted separately from other lots with different aromas?”

If you’re buying a large quantity of hops, there’s a greater chance your selection will be pelleted independently. If I was a brewer, I’d want to know how that applies to my order and how the pelleting process affected my order. It’s possible to go much deeper in the weeds on that subject, but I’d like to keep this article short. It’s reasonable to wonder how the pelleted product a brewer orders might vary from what he thinks he is getting … Remember the target image from above?

Variety Certification

The industry debated variety certification over 20 years ago when I was director at HGA. I wrote an article about it for the HGA newsletter at the time.

Back then, the industry was divided. Those were difficult times. Hop prices were at their lowest point in a generation. The cost of implementing such a program was touted as the reason the issue disappeared. To my knowledge it hasn’t resurfaced.

According to the 2001 Hop Growers of America Statistical Packet, the value of the U.S. crop was $127 million. In the 2021 Statistical Packet the value was $661 million. That’s a 520% increase in 20 years. Money might less of a concern in 2022 than it was in 2001.

I love a good conspiracy … UFOs, bigfoot, New World Order … the whole deal. So … naturally, I doubt that the cost of certification was ever the real reason behind the lack of support. I’ll keep the tin foil hat theories to myself, but here’s a couple things to consider:

· Was the real reason for the opposition to variety certification that the testing methods at the time would have increased awareness of the variability of variety characteristics making certification difficult if not impossible?

· Might the breadth of varietal characteristics reveal to potential customers that varieties are less unique than they believe?

The Science

A gas chromatograph (GC) test can reveal the oils in a hop sample[15]. In 2001, that would have likely been the type of test preformed. As you saw from the similarities between Cascade and Centennial above, it may not be clear which variety you have. In my former life as a dealer, the owner of a hop company once tried to sell me what he claimed were Centennials. There was a shortage, so I was suspicious. I ordered a GC test on them. The test couldn’t tell me what they were. It told me they weren’t Centennials though. I shared that with the guy thinking he’d want to know something like that. He called back the next day and asked if I wanted them at a lower price. I told him I didn’t want them at any price since there was no way to know what they were. That guy still sells hops today. Caveat Emptor!

That lack of clarity shouldn’t be the case today. During the past 20 years, technology has advanced. DNA fingerprinting is more affordable. There are devices like the Flongle from Nanopore Tech that make partial reads of DNA sequences in the field possible[16]. The Cascade genome has been sequenced[17]. If you’ve used 23andme.com or Ancestry.com, you have a good idea the results that DNA testing can produce in humans[18]. If you’re curious how DNA fingerprinting works with humans, check out this video from Bozeman Science.

Science seems intimidating at first, but I tried working with DNA myself. I performed some experiments on hemp last year and was surprised how simple isolating DNA was. The picture below was from my first attempt! If I can do that, it’s not rocket science.

Today, DNA fingerprinting can be used to identify different plant cultivars[19]. The cannabis industry is exploring how to use genomic images to do just that. Proponents of the idea believe it would be possible to do the following[20]:

Identification of cannabis cultivars using their unique genetic profile

Identification of plant species, varieties, clones, individuals, and even plant products

Guarantee genetic quality and ownership

Authenticate the nature and origin of the plant

Validate the genetic inventory and stockage

Register and protect new cannabis cultivars

Construction of evolutionary and phylogenetic trees

UC Davis Plant Identification Lab makes DNA-based variety identification available for varieties of almonds, apples, apricots, cherries, grapes, olives, peaches, pistachios, plums, strawberries and walnuts[21]. The same could be done for hops.

DNA fingerprinting could provide value to the people who own proprietary hop varieties. Brewers paying premium prices for proprietary hop varieties might be interested DNA variety certification. On orders over a certain size, it would be cost effective and offer peace of mind. It could settle cases where the variety is in question. Is this something to be concerned about? There are reasons other than the merchant I mentioned above who tried to sell me the mystery hops he called Centennials.

Off Types

There are off types in hop fields all around the world. Every hop seed represents a unique variety, not a clone of the mother plant[22]. Public hop breeding programs, like the one at Oregon State University in Corvallis, Oregon, create and collect seeds under controlled circumstances to take advantage of the resulting genetic diversity[23]. The story shared by Virgil Gamache Farms on their web site about how they discovered Amarillo® is one example how that’s not always a bad thing. If you haven’t heard the legend, here’s an excerpt from their web website:

“A few years after Virgil retired and passed the farm onto his sons, a discovery was made. An unusual hop was found growing out in a hop field. It was significantly different than anything that had been grown on the farm to date.”

The way to propagate hops to ensure 100% varietal integrity is to take softwood cuttings from a known existing plant that is true to type[24]. When farmers plant new acreage, however, they plant rhizomes (the roots) from an existing field of the same variety[25]. So long as the rhizomes in the ground are all from the same variety, they will be true to type. Most female hop plants (the ones that produce cones) are diploids. Diploids produce seeds[26]. Hop farmers try to maintain varietal integrity on their farms by roguing (routine removal of plants that exhibit off-type characteristics or undesirable traits)[27]. If there are rhizomes from off types in the soil … and if those rhizomes are the ones they dig up, those rhizomes will produce offspring of the desired variety with genetic mutations[28]. That’s why roguing is important. CLS Farms, in Moxee, Washington, says on their web site, “less than 1% of our hops are produced with off-type varietals making CLS hops the purest in the market today”[29].

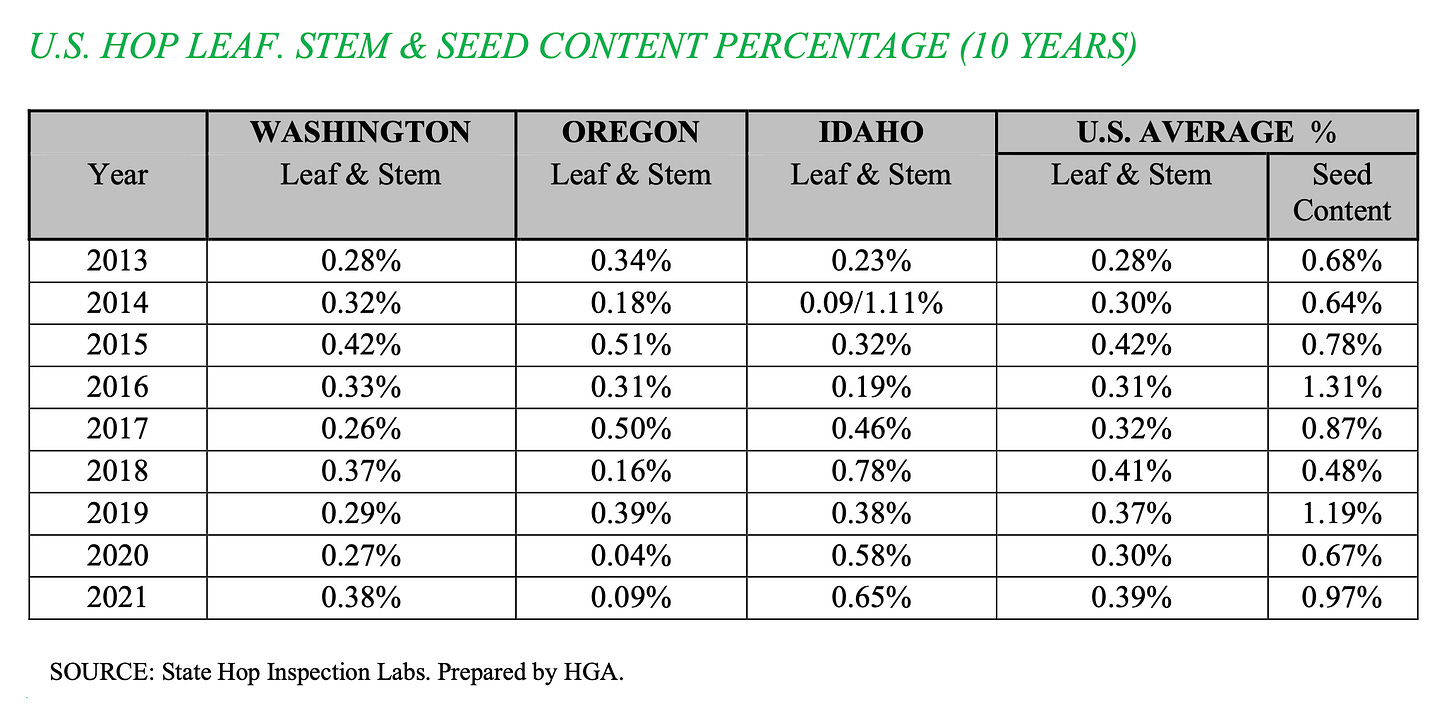

I don’t know if all farms measure the percentage of off types like CLS does. The 2021 Hop Growers of America Statistical Packet, however, lists the average seed content for Washington, Oregon and Idaho along with the U.S. average seed content. As you can see in the table below, seed content varies from year to year. In no year is the seed content zero.

The presence of seed means that open pollination has occurred. It means male plant DNA mixed with the female plants in the field. That creates the possibility for off types. The higher the seed count … the greater the possibility.

The Value

Proprietary varieties are by far the most valuable varieties the hop industry has ever created. The other side of that is that brewers today pay more for proprietary varieties than they have ever paid for public hops in the past. The word “brand”appears next to the names of proprietary varieties today. The Yakima Chief Ranches web page is a great example[30]. Why? Developing branded products creates greater value for the company that creates them. Public or generic products don’t create customer loyalty, name recognition, and trust for a company the same way branded proprietary varieties do[31]. Perhaps the brand is more valuable than the hops they represent. Brewers use these hop brands on their labels. Beer drinkers today recognize those brands. It’s an amazing change from just a generation ago. If brewers care about the variety and not just the brand name they are buying, it seems reasonable for them to have greater awareness about what defines that brand. Some sort of certification might not be necessary, but should it be an option? Considering the price being paid for hops today, it seems reasonable for brewers to know exactly what they are buying.

That’s my humble opinion as a recovering hop merchant. Talk amongst yourselves.

Thank you for investing your time to read this article. If you found something in it valuable, I hope you’ll consider sharing it with somebody else who might also enjoy it.

[1] https://hoohhops.com/8-hop-terpenes/

[2] The HSI is a measurement of the degradation of alpha and beta acids over time. Greater degradation is represented by a higher HSI number so the lower the HSI number the better.

[3] https://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/downloads/jq085p11m

[4] https://www.yakimachief.com/media/wysiwyg/Yakima_Chief_Hops_Varieties.pdf

[5] www.climate.gov/news-features/climate-and/climate-beer

[6] Bullseye art: https://www.pexels.com/photo/bullseye-center-illustration-round-416832/

[7] There are some sensitive people in the hop industry and I’m sure this will get their attention. So let me state here that I am not critical of Yakima Chief for the way they’ve presented their information. Quite the contrary in fact. This is (in my opinion as a recovering hop merchant) the proper way to present this type of information.

[8] https://www.yakimachief.com/media/wysiwyg/Yakima_Chief_Hops_Varieties.pdf

[9] https://www.homebrewersassociation.org/how-to-brew/hop-substitutions/

[10] https://science.howstuffworks.com/primary-colors.htm

[11] https://www.ncifm.com/how-many-colors-are-there-in-the-world/

[12] https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/2016/05/31/super-tasters-non-tasters-is-it-better-to-be-average/

[13] https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/making-sense-of-taste-2006-09/

[14] https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/2016/05/31/super-tasters-non-tasters-is-it-better-to-be-average/

[15] https://www.thermofisher.com/us/en/home/industrial/mass-spectrometry/mass-spectrometry-learning-center/gas-chromatography-mass-spectrometry-gc-ms-information.html

[16] https://nanoporetech.com/products/flongle

[17] http://hopbase.org/downloadCascadeHaplotigs.php

[18] If you’d like a clear and concise explanation of how DNA fingerprinting works when applied to humans, you’ll enjoy this video from Bozeman Science.

[19] https://biologywise.com/dna-fingerprinting-in-plants

[20] https://thecannabisindustry.org/member-blog-genetics-validation-certified-growers-and-cultivar-identification/

[21] https://fps.ucdavis.edu/dnamain.cfm

[22] https://firstkey.com/hop-breeding-bring-on-the-bitterness/

[23] https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Vegetative-propagation-of-hops-A-rhizomes-B-rooted-cutting_fig4_351831766

[24] https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Vegetative-propagation-of-hops-A-rhizomes-B-rooted-cutting_fig4_351831766

[25] https://www.usahops.org/enthusiasts/growing-season.html

[26] https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Diploid

[27] https://eorganic.org/node/386

[28] https://buyhoprhizomes.com/faq/

https://clsfarms.com

[30] https://www.yakimachiefranches.com/brands/detail.html?varietyid=1

[31] https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2021/03/24/the-importance-of-branding-in-business/?sh=20ff8fe67f71